Ask any football fan to name an Argentinian that has plied his trade in Serie A and Diego Maradona, Gabriel Batistuta and Javier Zanetti immediately spring to mind. Those who have a greater interest in Italian football will recall players such as Ariel Ortega and Abel Balbo, and once you delve deeper, the sheer scale of Argentinians that have played in Italy’s top league becomes clear.

This series of articles will take a look at some of those players and explore the circumstances surrounding their moves from South America to Italy, starting with the 1934 World Cup and the three Argentinian nationals who represented eventual winners, Italy.

So why did so many Argentinians come to play in Italy in the first place? Given Argentina’s location in South America and their native tongue, surely a career in Spain seems more logical. There is, however, a sensible explanation to the phenomenon.

After the unification of Italy in 1861, a mass emigration of Italians commenced. Argentina’s capital Buenos Aires was a favoured destination, second only to New York in number of Italian immigrants. As you might expect with immigration on such a large scale, Italian culture and language began to take hold in Argentina. By the 1930s however, political and economic instability caused by the Argentine coup d’état, prompted many to seek pastures new. For talented footballers, Italy offered cultural familiarity and the prospect of higher salaries.

During this period, Italy was under the rule of Fascist dictator, Benito Mussolini. Inspired by Adolf Hitler, who used the 1926 Olympic Games in Berlin as a tool to assert German supremacy, Mussolini seized his chance to promote Fascism by hosting the 1934 World Cup in Italy, despite the Italian national team never having participated in the tournament before. He understood what a strong national football team could provide; an increased sense of unity, an augmented status in the international community and a means of controlling the general populous. Thus, winning the tournament on home soil became paramount to the Italian Prime Minister, commonly known as Il Duce (The Leader).

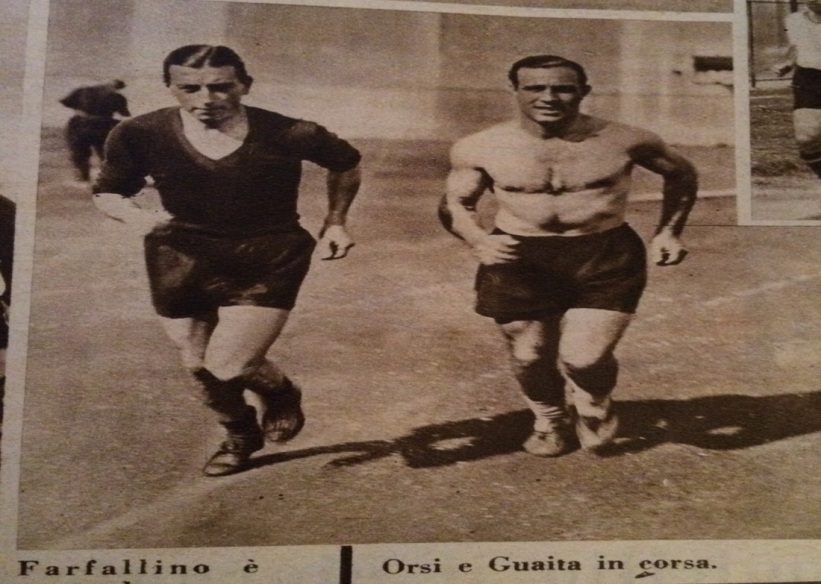

Vittorio Pozzo was the man entrusted with managing the Azzurri to glory in 1934. In order to achieve this, he called upon three Argentinian “oriundi” – an Italian term that refers to an immigrant of native ancestry. Luis Monti, Raimundo Orsi and Enrique Guaita had all already played for the Argentinian national team, but during this period players could chop and change national teams as they wished. It wasn’t until the early 1960s that FIFA outlawed playing for more than one national side.

To avoid contradicting the nationalist politics of the party, the Fascist propaganda machine was in full flow when emphasising the Italian heritage of the trio. Pozzo himself referred to their eligibility for national service, famously stating “if they can die for Italy, they can play for Italy.” The trio were all very popular at their clubs, and were largely well received by the Italian public.

Central defender Luis Monti was born in 1901 in Buenos Aires. A descendent of the Emilia-Romagna region, he is the only player to have ever represented two different countries in successive World Cup finals. Monti was first called up to the Argentine national side in 1924 and was a key player in the 1930 finals, scoring two goals en route to the final, where La Albiceleste lost 4-2 to Uruguay. It is reported that the hard tackling yet attack minded defender caught the eye of Mussolini in the 1930 final, and was duly offered a remunerative salary in order to sign for Juventus.

After his arrival he was convinced to accept Italian citizenship and he enjoyed a hugely successful career with La Vecchia Signora, winning four successive league titles. This did not go unnoticed and Pozzo was a huge admirer of the player nicknamed doble ancho, meaning “double wide” due to his large coverage of the field. Pozzo was convinced Monti could be the man to help link defence to attack, employing him as a deep-lying midfielder in his 2-3-5 formation.

Raimundo Orsi was born to Italian parents in Avellaneda and also found success with Juventus. Having originally been approached in 1927, he had to wait a year for his move to Italy due to “international restrictions”, complications which involved the Argentinians accusing the fascist government of paying for Orsi’s transfer fee rather than Juventus. “Mumo” became one of the stars of this hugely successful Juventus team, scoring 77 goals in 177 games. His appearances as an oriundo for the Azzurri have only been surpassed by another Argentinian born Italian international, Mauro Camaronesi.

Enrique Guaita, the third World Cup oriundo moved to Italy a little later than the other two, joining AS Roma from Estudiantes in 1933. A forward described as having great technique and speed, he finished the 1934/35 season as capocannoniere (top-scorer) with a tally of 28 goals, a record during the years in which the Italian top flight contained 16 teams.

All three oriundi were influential in the World Cup finals of 1934. Monti was hailed for his performance in Italy’s 1-0 semi-final triumph over a highly favoured Austrian side, his man marking stymieing Austria’s talisman Matthias Sindelar. Enrique Guaita also saved his most meaningful contribution to the semi-final, scoring the only goal of the game to send Pozzo’s men to the final.

The final against Czechoslovakia was played on June 10, 1934, at the National Stadium in Rome in front of 55,000 fans. Having struggled against the intricate passing game of the Czechs, the Italians fell 1-0 behind, only for Raimundo Orsi to score a second-half equaliser to send the tie to extra time. To the delight of Mussolini, Italy went on to win the game 2-1 courtesy of an Angelo Schiavo goal.

However, the oriundi were not awarded the recognition they deserved. Despite their hefty contribution, as well as the efforts made to emphasise their Italian roots, it is reported that the trio were controversially denied a special medal which was awarded to the rest of the squad by Mussolini. It was an action that emphasised the oriundi had simply been a dispensable cog in Mussolini’s fascist wheel, simply a means to an end.

After the World Cup, Monti stayed in Italy and commenced a career in management but Orsi and Guaita moved back to Argentina in 1935. In fact, Guaita left in a hurry, fearing that he may actually be called upon to die for Italy in the Italo-Abyssinian war.

Over 80-years on, the debate surrounding the legitimacy of Italy’s oriundi continues, with national coach Antonio Conte’s decision to call-up Brazilian-born forward Eder and Argentine-born midfielder Franco Vázquez stirring intense national debate. However the exploits of the oriundi in the Azzurri’s 1934 World Cup winning side has no doubt inspired other Argentinians to follow in their footsteps.

Despite the closing of the loophole that allowed players to play for more than one international team, players have continued to arrive in Italy from Argentina throughout the decades, right through to this season’s capocannoniere, Mauro Icardi.

Follow Chloe Beresford on Twitter: @ChloeJBeresford

Author Footnote

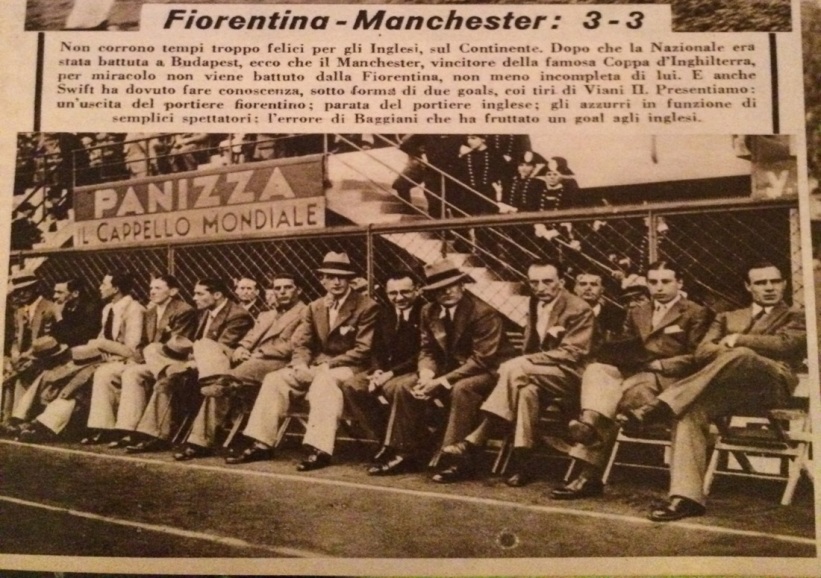

After discussing this article with my Dad, he reminded me that when my great-grandfather played in a friendly for Manchester City against Fiorentina in 1934 just before the World Cup started, the Italian national team were in attendance. We checked his antique copy of ‘Il Calcio illustrato’ from that year and found a picture clearly showing Raimundo Orsi (second right) watching my great-grandfather play (and score a goal) at the then named Stadio Berta in Florence. We also found many fantastic pictures of the Italian oriundi (included in the article), in what was an amazing and unexpected coincidence!