In the footballing world, where clichés abound, Leicester City’s improbable surge towards the Premier League is a genuine sporting fairytale. This time last year Leicester were on the verge of relegation. Now they are on the brink of winning one of the most prestigious titles in world football. According to ex-footballer turned pundit, Gary Lineker, the Foxes winning the English Premier League is simply something that does not happen in the game.

He is wrong, of course. Things like this do happen in football, just not very often.

In fact, you need to go back 30 years to a certain romantic city in northern Italy, more famed for Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and its summer opera season, to find a comparable footballing achievement.

The Celtic Bar in Verona is discreetly located on the north side of the meandering Adige River. The anonymous exterior of the building gives way to a snug lounge that replicates the best traditions of the ubiquitous Anglo Saxon watering hole. It offers a decent range of draft and bottled beers, including as good a pint of Tennents lager as you will find this side of the Brenner pass. Trust me, I’m a Scotsman.

A genial host, background music that shifts from subtle indie to sing-a-long Britpop, and a constant fare of English and Italian televised football in a city where it isn’t always easy to follow the British game.

Propping up the bar, you’ll invariably encounter respected sports journalist Matteo Fontana, who writes regularly for La Gazzetta dello Sport and Il Corriere. His knowledge of the beautiful game is as broad as it is deep.

Unfortunately, for me, his learning extends even to the Scottish game, where his ability to recall particular players, games and incidents, often puts my own powers of recall to shame. Indeed, he could tell me far more than I cared to remember about a certain less than vintage Scottish performance in 1990 against Central American World Cup debutants Costa Rica, who defeated Scotland 1-0 (or so he tells me).

Today we’ve got happier footballing memories to discuss.

In 1984-85, Hellas Verona, an unfashionable provincial club who just a couple of seasons previously had been playing in Serie B, achieved the impossible. They won Serie A. And this wasn’t a Serie A in the doldrums, lacking in quality. This was the era of Diego Maradona at Napoli (Napoli’s average attendance that season was a staggering 77,000), Platini at Juventus, Rummenigge at Inter, Falcao at Roma and Zico at Udinese.

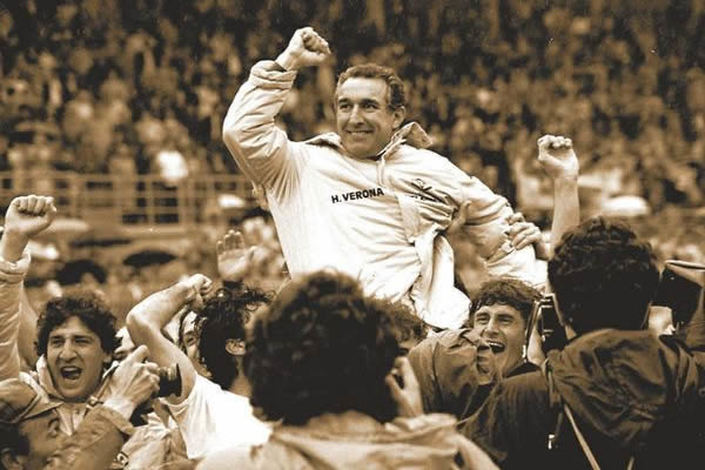

Fontana recently staged a play about this miraculous 1984-85 season from a fan’s perspective (think Skinner and Badiel’s Fantasy Football meets Trainspotting with events on the pitch providing the dramatic backdrop). He has now turned his attention to the coach of that legendary Hellas Verona team, Osvaldo Bagnoli. Although a legend in Verona, Bagnoli is not widely known outside Italy.

Fontana’s book “Il miracoliere – Osvaldo Bagnoli, l’allenatore operaio” was published recently (in Italian) and is currently enjoying favourable coverage in the Italian sports media. Although the idiosyncratic coach is the central protagonist in the book, Fontana’s writing is much deeper than a simple sporting biography. Bagnoli’s footballing career is explored within the context of post-war Italian society and the 1984-85 season is set against the backdrop of the turbulent social and economic events of the time, both local, national and international.

I sat down with Matteo over a beer (Tennents, of course) to chat about Bagnoli and that amazing 1984-85 season. I started off by asking him if he thought what Hellas Verona achieved in 1985 and what Leicester are on the brink of achieving now are comparable.

MF: There are similarities. But in some ways, if Leicester were to win the Premier League, the surprise would be even greater. Verona’s title, in fact, came on the back of a couple of decent seasons in Serie A [in the 1983-84 season, Verona finished in sixth place] and they were losing finalists twice in a row in the Coppa Italia. Claudio Ranieri’s team, on the other hand, experienced a difficult relegation battle last season. However, the comparison is a correct and useful one in order to understand the magnitude of such an accomplishment.

RH: Who was Bagnoli and why have you decided to tell his story now?

MF: For Verona, Osvaldo Bagnoli is comparable to Bill Shankly at Liverpool: he made people happy. I was a child, my house – my family has always supported, for generations, the team of the city – when he appeared on television, or we read his words in the newspapers, it was like listening to the sermon of a priest: there could be no doubts about his message. He was, and is, a calm, honest person. And he was a great coach. And not only for Verona. But being so quiet and not at all attracted to the limelight, his contribution to football has not really been recognised by the press and commentators.

RH: How do you explain his incredible achievement in 1984/85?

MF: Bagnoli built a solid group, always with a propensity towards attack. In Italy in those years, there was still the strong legacy of “catenaccio”. Verona was one of those teams who broke the “lock”. And from that tactical idea, which he developed over the years, the miracle of the scudetto was born. But the victory also came from the moral fibre within the dressing room: Bagnoli was a father to his boys.

RH: At what point during that season did you begin to think that Verona could actually win the league?

MF: Osvaldo Bagnoli explained several times that he felt that the final victory was near after the 1-1 ‘victory’ in Turin against Juventus [played on 24 February 1985, this result kept Verona at the top of the table with just 10 games to play]. On a personal level, in my memory, I think the 3-1 comeback, in which Verona’s second half performance destroyed Fiorentina, was the time when, as a child, I understood that we could achieve this dream.

I will never forget the context of that event and how I followed the game. I listened to the first half at home with my parents. At half time Verona were down 1-0. For the second half we listened with my maternal grandmother, a wonderful sweet woman. After that match I really did believe! [The match Matteo is describing took place on 17 March 1985. Verona were one down at half-time, but a rare second half goal from moustachioed defender Silvano Fontolan and two late finishes by top striker Giuseppe Galderisi ensured a decisive victory for Verona, putting them 3 points clear at the top with 8 games to play].

RH: What is your strongest personal memory from that season?

MF: Every single moment, every single match is carved in my memory. I was lucky, I was only eight years old but I saw 11 out of 15 home games from the stands of the legendary Bentegodi stadium. The final act that remains with me is that of the party for the league title, the last day of the season, 4-2 at home against Avellino. That day I took my First Communion in the morning and should have spent the afternoon celebrating that with my relatives. But there were no doubts about going to the game. So, we went to the match and celebrated at the Bentegodi. By the time we got back to the Communion celebrations the buffet was already finished!

RH: What did/ does it mean for a city like Verona to win the league?

MF: It means to make history and to leave a mark that can never be forgotten. Verona is a quiet and reserved city, but in the days of the championship it turned into a small Rio de Janeiro. The imprint of that triumph remains unchanged in the memory, even after three decades. Fathers tell their sons. Verona’s 1984-85 Scudetto is oral history, like the narratives of the bards of ancient Greece!

RH: Is it possible for a so called provincial team like Hellas Verona to ever win Serie A again?

MF: As things stand in Italian football at the moment I would have to say 99% no. Then I look at Leicester City in England, with the hope that they will actually complete their superb journey, and I think of the 1% that remains….

RH: What has gone wrong for Hellas Verona this season? [bottom of Serie A, Verona are almost certain to be relegated to Serie B]

MF: The owner made a long list of errors. Fatal was the change in the area of the sporting director [in May 2015 Verona announced the departure of Sean Sogliano, Director of Sport, after 3 successful seasons with the club]. Another mistake was giving too much power to a management team who couldn’t find the correct response to the shortcomings that were immediately obvious.

There has also been a component of bad luck, because many players have had physical problems, including key striker Luca Toni. But the mistakes are much greater in number and effect than the harm caused by bad luck. This is, for now, the worst ever Verona in Serie A. And relegation is a necessary consequence.

RH: Final question. Can Verona survive in A?

MF: Not now. Not any more. It’s better that we prepare for the future in Serie B and look for a quick return to the top flight.

Our interview is over. It’s been thrilling to observe how Verona’s famous Scudetto can still provoke such raw and vivid memories, even after all this time.

Of course, for Verona things have never been the same since those halcyon days in the mid-1980s when shorts were short, players were honest and gialloblù really was gialloblù.

The following season, Verona finished a disappointing 10th, but in the 1986-87 they returned to form, finishing 4th and qualifying for the UEFA Cup. In 1987-1988 they achieved their best ever European result, reaching the quarter-finals of the UEFA Cup. By 1990, Italian football was in its absolute prime. Names like Maradona, Van Basten, Roberto Baggio, Toto Schillaci, Rudi Völler, Jurgen Klinsmann and Lothar Matthäus were regularly on the score sheet and Italy itself was preparing for what would be an era-defining World Cup. But for Hellas Verona, the dream was over. Financial difficulties off the field and poor results on the pitch culminated in defeat away to Cesena on the last day of the 1989-90 season. Verona finished the campaign third-from bottom and the team that won the title just 5 years previously was relegated to Serie B.

Although they bounced back to the top flight the following season, in the 1991-92 season they again finished third from bottom and again found themselves in Serie B. This time there was no quick comeback and Verona spent much of the next 20 years in the lower leagues.

As for Bagnoli, he left Verona in 1990. He had a couple of successful seasons with Genoa (earning fourth place in the 1990-1991 season, the team’s best post-war finish and, in a famous victory, eliminated Liverpool from the UEFA Cup at Anfield in 1992). He saw out the final 2 years of his career at Inter, finishing second in his first season before being dismissed in February 1994 after a poor start to his second season with the Milan club. At the age of 59 his football career was over.

In doing the impossible and winning the league with Verona, Osvaldo Bagnoli and his legendary team achieved sporting immortality. Very soon the players, managers and fans of Leicester City may well know how that feels. They won’t be disappointed!

With a special Grazie to journalist Matteo Fontana