In the Savona province of Northern Italy, you will find Vado Ligure, a commercial town known for its port, electric power plant – whose twin towers dominate the skyline – and the Bombardier railway construction company. But hidden amongst this busy centre of industry is a little jewel of Calcio and its name is Vado FC 1913. Their achievement is not of multiple Scudetti or a fine collection of European silverware, instead they are the first winners of Italy’s domestic cup competition – the Coppa Italia.

As the club’s name suggests, they were founded in 1913, headed by a consortium fronted by Angelo Morixe, which consisted of the Babboni brothers – Achille, Lino and Giovanni. They were accompanied by other work friends at the Westinghouse railway company which later became the Bombardier railway company, as it is known today.

Lino Pizzorno was chosen as the clubs first President with Nicolo Gambetta and Ragini Pasuale as club supervisor and secretary respectively. After much discussion the colours of red and blue were chosen for the club in tribute to Genoa Cricket and Football Club, who at the time were the top team in Italy.

The pitch was sandwiched between the Fumagalli paint factory – which still exists today – and the town’s train station. From 1913 until 1919, the club participated in friendly games, mainly against teams like Savona, Veloce, Speranza and Varazze. They had all been founded before Vado and these more established teams gave the Rossoblu a solid test. For six years, the club were forced to play non-competitive football due to their formation, which occurred just a year before World War One.

As Europe and Italy started to recover from the devastating consequences of the war, sport became both a means of escapism and an avenue through which the populace could embrace the hope of a better future. Although Vado FC struggled during the immediate years after the war, their fortunes improved in 1922 when they earned a historic promotion to the Seconda Division.

After this triumph, Vado were entered into the inaugural edition of a new national cup competition the Coppa Italia. This competition was born out of a dispute between the FIGC and the major teams competing in the Prima Categoria. The teams asked for a reduction of the number of participants in the 1a Divisione of the Prima Categoria, the top level of Italian football at the time. But, fearing for their future without a chance of promotion, smaller clubs rejected the proposal.

The major teams such as Juventus, Pro Vercelli, Torino, Inter, Genoa, La Spezia and Unione Sportiva Livorno broke away to form a new league under the governance of the Confederazione Calcistica Italiana (CCI). This dispute only lasted one season but for the first edition of the Coppa Italia, only clubs under the control of the FIGC were invited to take part, which included teams from the Prima Categoria, Promozione and the Terza Categoria.

However, their cup run was nearly over before it began, as Vado needed extra time to see off Fiorente 4-3 in the first round. The next two rounds were negotiated with comparable ease, as the Rossoblu beat Genoa based club, Molassana, 5-1 and the Milan based, Juventus Italia 2-0. Vado’s quarter-final opponents, Pro Livorno (who later merged with Unione Sportive Livorno to create today’s incarnate), looked a much sterner task. The Tuscans had just won promotion to the Prima Categoria and were well-rested having been given byes up until the quarter final stage (the first Coppa Italia had started with an odd number of teams). Despite being underdogs however, Vado defied the odds and prevailed by a solitary goal. The fairy tale continued.

The semi-finals proved to both entertaining and also controversial, Vado drew another Tuscan club in Libertas Firenze, who had also received byes from the first round until the quarter finals. In fact, Libertas hadn’t even played their quarter after their opponents, Valenzana, withdrew from the competition. Thus, the odds were stacked against Vado once again. But their never say die attitude proved too much for Libertas and an extra time goal sent the team of mostly railway workers into their first ever final.

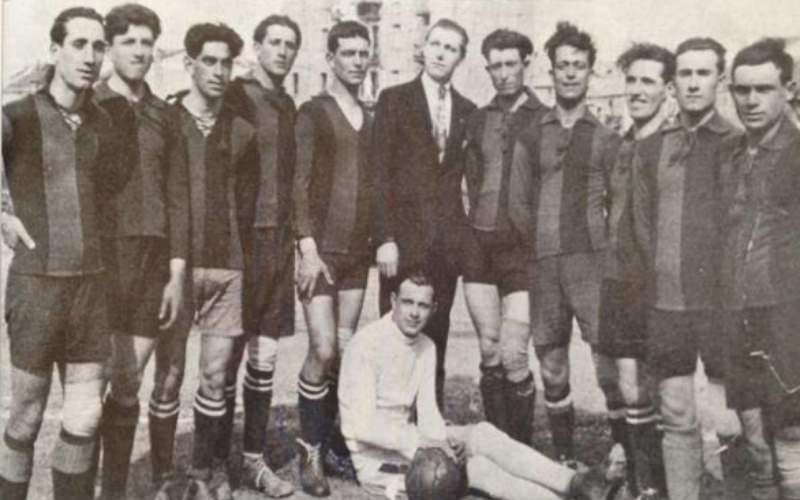

Udinese awaited Vado in the final, which was was played in Vado Ligure on July 16, 1922. Although the railwaymen had home advantage once again, the perceived technical superiority of their visitors had the Rossoblu second favourites. The three Babboni brothers lined up along with Enrico Romano, who had the fantastic nickname of Testina D’Oro, or ‘Head of Gold’, after apparently scoring 13 headed goals in one friendly game.

Vado also boasted a young left winger by the name of Virgilio Levratto, one of the Rossoblu’s more gifted players. The game progressed as expected, with Udinese pinning their opponents back but Vado’s resolve ensured they took the game to extra time. As Udinese’s exertions took their toll, Vado looked fresher and Levratto, who had been shackled all game, started to find some freedom. As extra time was drawing to a conclusion, the Udinese players started to complain about the light or rather the lack of it. Being 1922, there were no floodlights and Udinese hoped the game could be stopped and replayed in Friuli. However, the referee declined and at the end of extra time, he decided to settle the game that night by playing for a “golden goal”.

A disgruntled Udinese team pushed forward hoping their technical ability would be enough to bring the game to a conclusion. But seven minutes into the golden goal period, an Udinese attack broke down and the ball was seized upon by Lino Babboni. Together with Levratto, the duo launched a speedy counterattack. Levratto received a pass from Lino and from outside the penalty area unleashed a shot which found the top left corner to win the game. Myths and fables have arisen about this goal. Depending on which version you believe, the shot either ripped the net and the ball hit a window on the sentry tower in the corner of the ground, or the ball was hit so hard it burst as it flew into the top corner.

Regardless of whether either is true, the fact remains that the story of the Rossoblu’s success does not need any added twists or spice. After only three seasons playing competitive football, Vado FC 1913 had achieved promotion and become the very first winners of the Coppa Italia, a remarkable achievement for any club.

The scorer of the winning goal, Virgilio Levratto, went on to have a distinguished career, playing for established clubs such as Verona, Lazio and Genoa. He also won a bronze medal with Italy in the 1928 Olympics

Much of Vado’s success was based on stubbornness both of a physical and mental nature, adopting a frame of mind common in Vado Ligure at the time. The area was involved in the early days of Italian communism and was looked upon as an outlier in Italy, much of which was embracing the ideas of the National Fascist Party. Using this “outsider” mentality, Vado Fc took every game as statement of their identity and it proved perfect motivation. This helped the Babboni brothers and their team mates cement their place in history.

Today, the club is playing in Serie D and throughout their long history have spent their time in the lower leagues of Italian football. But they have their place in the history books as the first winners of the Coppa Italia, and no one can take that away from Vado FC.