On a June evening in Porto in 2004, a Scandinavian derby took place in a decisive game of the Euro 2004 group stage. Sweden trailed 2-1 going into the closing stages, but managed to equalise in the 89th minute of the match.

A 2-2 draw is not the most common score-line, but most Italians had tipped the result beforehand. It was a result that confirmed Sweden and their neighbours Denmark would qualify, whilst Italy were eliminated at the first hurdle. Both sides denied talk of an agreement before the game, and defended their performance afterwards, even if years later it emerged that the players had discussed the desired result, and had clearly settled for the score-line. Italy is a nation fond of conspiracy theories, and this, just two years on from the debacle in Korea, was another chance to feel aggrieved, to bitterly complain, to exonerate la Nazionale of any blame, because there were darker forces at work.

The Italians had good reason to be unhappy at the 2002 World Cup; Ecuadorean referee Byron Moreno harshly sent off Francesco Totti, ignored several vicious South Korean tackles, and awarded South Korea a debatable penalty. Italy also had five goals disallowed in the group stage, at least three of which ought to have stood. Moreno would even go on to appear on Italian television playing the role of the pantomime villain, where he was mocked and abused, with the audience stopping just short of throwing rotten tomatoes at the ridiculed figure.

In 2004, though, the Scandinavian ‘agreement’ was a convenient excuse. Yes, it seems rather strange that Denmark were dominating the game but conceded a late equaliser which produced the perfect result. Yes, Swedish and Danish players have since admitted that they colluded before and during the game. But who could blame them? Both sides knew that a defeat would risk elimination, whilst a result that is not too common, but is certainly credible, stood tantalising in front of both sides, allowing both to progress.

This was an Italy side containing Gigi Buffon, Alessandro Nesta, Fabio Cannavaro, Andrea Pirlo, Francesco Totti and Christian Vieri. It was a squad full of players who would go on to win the World Cup in Germany two years later. This was not a team that should have left things to chance, that should have been relying on the result between Denmark and Sweden in the final group game.

Italy had played out a dire 0-0 draw with Denmark in their opening game of the tournament, with Totti lucky to avoid a red card for spitting at Christian Poulsen. It was a temporary reprieve, as Totti was banned after the game for three matches, which ultimately ended his tournament. Still, Italy could call upon Alessandro Del Piero as a replacement as they headed into their game against Sweden, who had beaten Bulgaria 5-0 in their opening fixture. Antonio Cassano was also in the wunderkind phase of his career.

Italy led against Sweden in Porto through a Cassano first-half goal, but this was Giovanni Trapattoni’s Italy. Failing to learn from previous mistakes, the Azzurri settled for the 1-0. A young Zlatan Ibrahimovic had other ideas; he produced an audacious flick from the edge of the six-yard box, facing away from goal, with the ball somehow looping over Buffon and Vieri on the goal-line into the top corner. Ibrahimovic became part of an unwelcome Italian tradition, joining an Italian side shortly after scoring a vital goal against the Azzurri in a major tournament, following in the footsteps of his soon-to-be team-mate David Trezeguet, who scored for France against Italy in the Euro 2000 final.

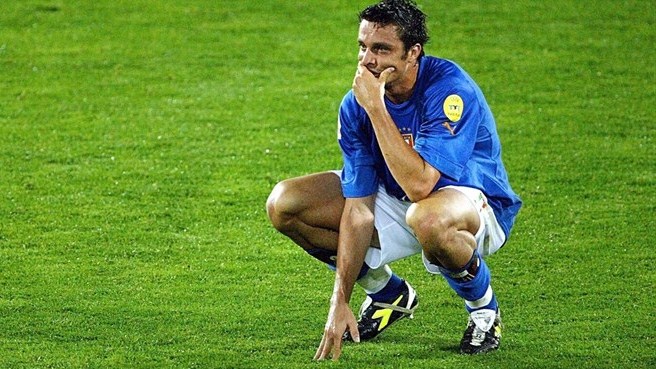

Trapattoni’s side now found themselves in a perilous position; goal difference was of no importance, so bettering Denmark’s 2-0 win over Bulgaria would have meant little. The decider, should Sweden and Denmark draw, would be their head-to-head record. Italy had drawn 0-0 and 1-1 against the Scandinavians, so a 2-2 draw between them would see them both through on goals scored within the head-to-head matches. Italy eventually beat Bulgaria 2-1, but only after going 1-0 down to a side who had failed to score a single goal in their first two matches.

What now looks a vintage Italy squad had only themselves – and their over-cautious manager – to blame for their eventual exit. To many outside observers, Italy has long been the home of pragmatic football, with tight, physical defences and 1-0 victories two of the major stereotypes of calcio. Indeed, many in Italy have traditionally considered it somehow ‘unsporting’ for a team who has nothing to play for towards the end of the season to actually ‘try’ against opponents fighting for a title or to avoid relegation. It is therefore a little rich that such a fuss was caused about a pragmatic, understandable stance taken by Sweden and Denmark, one which allowed both to progress rather than risking elimination for one of the neighbours. The proximity of the two countries added fuel to the Italian fire, but any two teams might have had similar ideas and come to a similar mutually-beneficial conclusion.

So when Italy face Sweden in a week and a half, they should not see the game as a revenge mission. Most of the players from the 2004 Sweden team have long since retired, and they only did what they had to do to ensure their own qualification in the least risky way. One man from that team does remain, though, and he should figure much more highly in Italian thoughts than the alleged ‘conspiracy’ of 2004.

When the sides met in 2004, Ibrahimovic, still at Ajax before the tournament, announced his talent to a wider audience. This time around, he is likely to play his last major international tournament and will come up against many familiar foes from his time at Juventus, AC Milan and Inter. Italy would be better to focus their attention on shackling the striker, who would love to make his mark on another European championship against the country where he played for so much of his career.