Type ‘Paolo Negro’ into the search bar on Facebook and the first result that pops up is a page called ‘Autogol di Paolo Negro’ (Paolo Negro’s own goal). The profile picture of the page is a funny photomontage of Negro wearing a Diadora-branded Roma shirt, the one the Giallorossi used at the turn of the millennium, with the orange collar and the stylised wolf profile on both sleeves.

The page has been inactive for quite a while now. The last post dates back to 16 April 2014, the day Negro celebrates his birthday, and it reads: ‘Buon compleanno bomber’ (happy birthday, goalscorer). Apart from this, there is nothing more than a couple of posts from 2009 reminding almost 3000 followers that the ‘past is unforgettable’, as well as some photos of the 2013 Coppa Italia final scoreboard. These are uploaded by Lazio fans as a riposte and reminder to Romanisti, who continue to mock them about Negro’s own goal.

Facebook pages are just the tip of this rivalry’s iceberg; one that pervades every wrinkle of Rome’s social fabric. Nonetheless, they can be interpreted as a litmus test for a derby which is lived by the inhabitants of the city, not only on two days, but all year long. A derby comprised of jokes, mockery, murals, songs and much more.Poor Paolo Negro became one of the favourite subjects of this dialectic battle that consumes Romans every day. His status as satirical icon among red-and-yellow supporters is still strong today. And yet, before becoming all this, he was just one of the many footballers who arrived in the Capital from afar.

Paolo Negro was born 44 years ago, in Arzignano, a town near Vicenza in northern Italy. He started playing as a forward, but his feet were what they were, and his first coach at Brescia decided to turn him into a defender. He moved to Bologna in 1990, only to return to Brescia two years later. In the summer of 1993, when Lazio decided to buy him, Negro was a solid defender. He was physically explosive, good in the air and already had ten caps for the under-21 national team. As everyone said at the time, it was a good deal for all involved.

His years at Lazio went as fast as the wind. He was there when they won the Scudetto and Coppa Italia in the 1999-00 season, and he was there when they lifted the 1999 UEFA Super Cup. These were just a few of the trophies won by the Biancocelesti. Paolo Negro formed part of one of the strongest Lazio sides of all time, playing with legends like Juan Sebastián Verón, Alessandro Nesta, Pavel Nedvěd, Dejan Stanković and Roberto Mancini.

Being in the squad since a young age, Negro’s love for the Biancocelesti shirt was genuine, despite not being a son of Rome. He was the kind of footballer every great team can’t do without: a utility player, an obedient and functional cog in the wheel. He was not a history-maker, nor the kind of player that would appear on the Corriere dello Sport’s front page on a Monday morning. He had never thought that, on a cold December evening, he would secure his place in the hall of derby heroes. Although, unfortunately for Negro, he did not enter through the main door, but instead found himself pushed in through the side entrance.

At the end of September 2000, the euphoria surrounding their second-ever Scudetto had mostly dissipated and Lazio were ready to face another tough campaign. The season started unusually late due to Euro 2000, World Cup qualification rounds and the Sydney Olympic Games. But right from the start, it was clear that Lazio’s main opponent were inside the city walls. With the purchases of Emerson, Walter Samuel and Gabriel Omar Batistuta, Roma were certainly among the teams to beat.

The first turning point of the season came on 17 December in the Derby della Capitale. Roma were first in the table and Lazio were fourth; with Juventus and Atalanta between them. The Stadio Olimpico was a sell-out, with just over 80, 000 spectators brimming with anticipation. But it soon became clear that this would not be a classic. There was a palpable tension in the air and though the players demonstrated plenty of physical exuberance, little happened of note – except for Cafu’s famous series of sombreros over Nedvěd’s head.

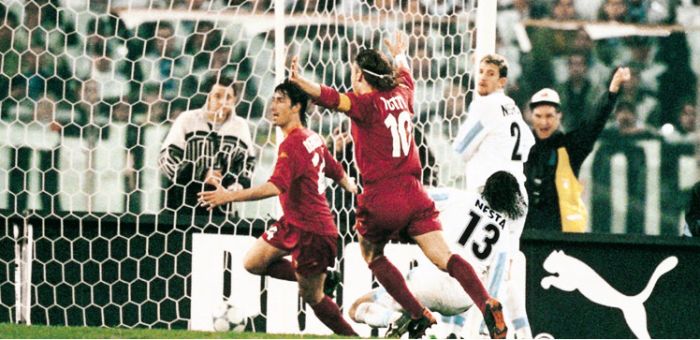

But on 70 minutes, the almost bored public were suddenly shaken from their numbness. Cafu crossed the ball into the box from the right flank for Cristiano Zanetti to head toward goal. Lazio goalkeeper Angelo Peruzzi parried the ball into the path of Nesta, who instinctively tried to sweep it away with his right foot. Unfortunately for him and his teammate, he directed the ball towards Paolo Negro instead, who was standing less than one-metre away from Nesta.

In that very instant, time stopped. A blink of an eye seemed to last ten minutes as Negro realised he was a few nanoseconds away from becoming a legendary figure. The worst kind of legendary figure. When time started ticking again, it was already too late. The poor defender could do nothing but feel the ball hitting his body and then entering the unprotected net, which was directly in front of him. The moment sparked jubilance among Roma supporters.

As they started to celebrate uncontrollably, the whole world seemed to be falling in on Negro: he was now a symbol of Giallorossi joy. At that point, he was already aware that he would remain so for many years to come, probably for his entire life.

In the 20 minutes remaining, Lazio tried everything to spare their teammate the unbearable dishonour of having granted their city rivals victory in a crucial derby. But the result remained until the final whistle, which signaled an opening of the gates of hell for Paolo Negro.

From that day on, nothing was the same in Rome. That surname is etched into the memory of every Romanista. It is one of the most common reference points when they write banners or sing stadium chants, and every year the anniversary of that derby is celebrated with new and more hilarious slogans, not to mention all the wishes Negro keeps on receiving from Roma supporters every time it’s his birthday. He is genuinely lauded as though he were a player who scored a hat-trick in the derby. Perhaps more.

Negro moved to Siena in 2005 and retired in 2007. After three-years, he changed his mind and played for one year at Cerveteri, in the Promozione (the seventh tier of the Italian football system), before starting his coaching career.

He will probably never be able to dissociate his name from that episode, not in a million years. Romanisti will never cease to find banners like ‘Nesta, mark Negro closely!’ funny, nor will they stop calling Negro ‘one of us’ and thanking him for that unexpected gift.

This is the Derby della Capitale: the match every true Roman is waiting for, the moment when the whole city stops, a game that can turn mortals into immortals. Even if some are turned against their will.

Words by Franco Ficetola: @Franco92C14

Franco is a son of Rome who grew up admiring Totti’s assists and chasing a ball through the streets of the capital’s suburbs. Now he spends most of his time watching football matches, regardless of the league, the country or the level. He also writes for @JustFootball.