If you were to ask most people to choose one game with which to showcase the philosophy and mentality of Italian football, they probably wouldn’t pick a 12-goal thriller. While high-scoring games may be taken for granted as entertaining spectacles in some countries, in Italy, they have historically been considered as anomalies. In fact, they contradict everything that the game stands for.

A big scoreline represents a flawed game. For such an event to occur, something drastic must have gone awry. Perhaps the tactics or formation were wrong, or the defensive line were particularly calamitous that day. But whatever the reason, when such a game occurs in Italy, it is analysed with forensic precision, not because it is entertaining, but because the cause of such a malaise must be identified and never repeated.

One such game occurred at San Siro on 15 October 1972, when AC Milan defeated Atalanta by a record 9-3 scoreline. And despite the atypical nature of that clash, it presents us with the perfect opportunity to explore the psychological structure of Italian football.

The game was painted on a familiar canvas: the hosts were one of the title favourites, while the visitors were amongst the front-runners to face the drop. As a result, it was expected that the team from Bergamo would turn up and play for a 0-0 draw, just as Ternana (the team that eventually finished bottom) had done so successfully when they hosted the Rossoneri at Stadio Libero Liberati just a week earlier

The visitors were certainly not known for leaking goals. In fact, over the course of that season, Atalanta recorded a total of seven draws on the road, five of them with 0-0 scorelines. In their 15 home games, only two teams (Juventus and Sampdoria) scored more than a single goal at Stadio Atleti Azzurri d’Italia and no team scored more than twice. In fact, 10 of their home games featured a single goal or less.

Moreover, when Giulio Corsini’s men arrived in Milan, they had played six competitive matches that season (four in Group 6 of the Coppa Italia and two in Serie A) and had yet to concede a goal. If anything, they were considered tactically astute and tough to beat, so what happened on that exceptional afternoon in October?

The initial reaction amongst observers in Italy was not to marvel at this goal-ridden spectacle but to don a white body suit, pick through the remains, and dust for fingerprints. There was a rush to examine the evidence and be the first to identify the culprits of this shambles.

Initial examinations by the press identified Corsini’s changes to the midfield set-up as the root of the problem. He sacrificed the attacking threat of Alberto Carelli in order to man-mark Gianni Rivera, and positioned Giuseppe Picella in a free role in front of the back line, a move also designed to stop the playmaker. However, the decision to block Rivera at whatever cost ultimately proved to be flawed.

The great Gianni Rivera in the iconic Red and Black of AC Milan

The great Gianni Rivera in the iconic Red and Black of AC Milan

Carelli, unused to such a role, struggled to track the midfielder, affording him space to operate behind the attacking trident of Luciano Chiarugi, Alberto Bigon and Pierino Prati. By the time he was closed down by Picella, it was too late as the ball had been offloaded to Romeo Benetti or Alberto Bigon, who penetrated the danger areas with their clever runs. This trend continued for the opening period of the game, with Rivera managing to evade his shepherds with ease while orchestrating countless attacking moves.

To be fair to the Atalanta boss, he did alter the midfield shape once it became clear that it was not working. But with the score at 4-1 after 40 minutes, it seemed as if a psychological seed had already been planted and the agenda of the game had been set.

The next exhibit presented by the prosecutors was the Atalanta backline. The usually solid Giacomo Vianello failed to impose himself on Pierino Prati, who lived up to his nickname of “the pest.” Likewise, Antonio Maggioni struggled to cope with the trickery of Chiarugi, while Giancarlo Savoia looked way off the pace after a long spell out injured.

But despite the mounting stack of evidence and identity parade of suspects, there were still questions that needed to be answered before the jury could return their final verdict. For example, why did Milan keep pushing for more goals? At the time, it was normal practice for any Italian team that opened up a three or four goal lead to sit back and protect their advantage. To continue punishing the opposition for the sake of it was considered wasteful and somewhat disrespectful. However, as both Romeo Benetti and Nereo Rocco pointed out, Atalanta were still creating chances and posed a threat (they actually won nine corners to Milan’s three), so to pull up the oars at any stage would have been more disrespectful to the opposition.

The final explanation for what happened that day goes beyond the normal realms of tactical and technical analysis. The truth is, Milan put in a magical performance. From an attacking point of view, everything they did went right; their passing was exemplary, their flicks, tricks and feints all came off, and their set pieces were delivered with precision. What’s more, their movement was bewildering and their dribbling sublime.

As if that was not enough, everything seemed to go their way. When the ball was spilled or deflected, it went to a Milan player and every clearance or second ball fell to their feet. It was as if the stars had aligned to create something preternatural, something inevitable.

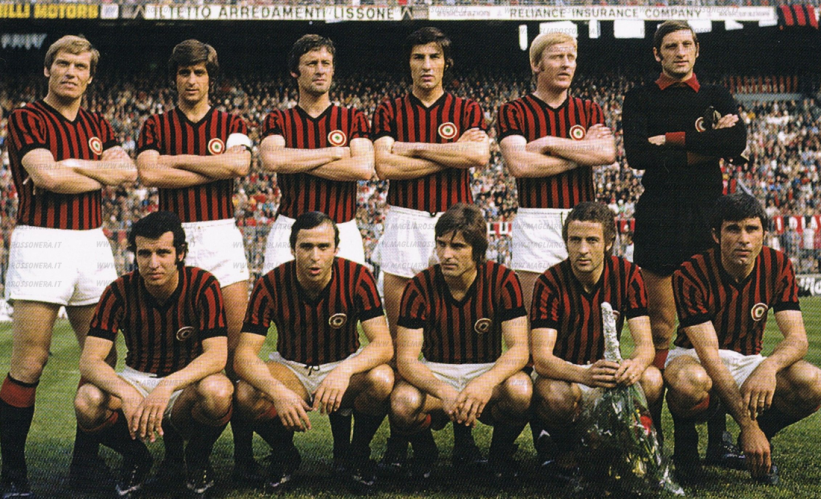

The Milan side of the 1972/73 campaign, lining up for a game later that season against Cagliari

The Milan side of the 1972/73 campaign, lining up for a game later that season against Cagliari

The profundity of the unfolding events proved too much for Atalanta goalkeeper, Pietro Pianta. By the time the seventh Milan goal went in, he became overwhelmed by anxiousness and was unable to continue. As he left the field (to be replaced by Marcello Grassi) he was visibly shaking and received a sympathetic standing ovation from the crowd.

The fans were also perplexed by what they witnessed that day. The taunting chants of “Serie B” from the home crowd eventually faded as the goals continued to flow and the scoreboard operator struggled to keep up.

Once the autopsy was complete, the final diagnosis was not conclusive. Instead, it was decided that the game that became known as “La Grande Abbuffata” (the great feast) was a freak result, and that many factors had conspired to produce this excruciating spectacle. To this day, it remains the highest scoring game in Serie A history.

When the teams met in the reverse fixture later in the season, normal service was resumed as they played out a 1-1 draw. But for Atalanta, the result in Milan proved decisive as they were eventually relegated on goal difference. Had La Dea conceded just two goals less, they would have remained in the top flight.

Meanwhile, Milan went on to lift the European Cup Winners Cup by defeating Leeds United 1-0 in Thessaloniki on 16 May, 1973. Just four days later, they looked all set to bag their 10th Scudetto title when they travelled to the Bentegodi Stadium to face relegation-threatened Hellas Verona needing just a draw. Nereo Rocco had asked for the game be moved due to their European exertions but the request had been denied.

Remarkably, Milan were involved in yet another high-scoring encounter. But this time they came out on the wrong end of a 5-3 scoreline. Just as Rocco had predicted, his team were suffering from fatigue and struggled to cope with the high-intensity approach of the opposition. The result lifted Verona into 10th place in the table, while Milan were pipped to the title by a single point by Juventus, who edged to a 2-1 win at Roma.

Milan XI: Pierangelo Belli, Giulio Zignoli, Angelo Anquilletti, Roberto Rosato, Karl-Heinz Schnellinger, Romeo Benetti, Gianni Rivera, Giorgio Biasiolo, Alberto Bigon, Pierino Prati, Luciano Chiarugi (67′ Magherini)

Atalanta XI: Pietro Pianta (56′ Grassi), Giacomo Vianello, Bruno Divina, Giancarlo Savoia, Antonio Maggioni, Giovanni Pirola, Giuseppe Picella, Raffaello Vernacchia, Giovanni Sacco, Gian Piero Ghio, Alberto Carelli

Goals: Prati (16’, 55’, 90’), Bigon (30’, 64’), Divina (33’), Rivera (35’, 52’), Benetti (40’), Chiarugi (50’), Ghio (54’), Carelli (88’)