Paolo Mantovani didn’t fit the traditional mould for Italian football presidents. Self-effacing, quiet and open, he controlled Sampdoria with thought and love. His time in charge of the Blucerchiati was filled with silverware and superstars; he invested heavily and reaped the rewards. But underlying the baubles, the glitz and the honour that came with his presidency was a strangely heartfelt message, one that stated it was possible to win against the odds without sacrificing important principles. Perhaps the truest testament to Mantovani’s character is that, even when at the grubbiest, highest echelons of calcio, he retained his dignity.

Born in Rome, Mantovani grew up a Lazio fan, though it wasn’t until a move to Genoa in his mid-20s that the football world opened its doors to him. He had an appreciation for Liguria’s capital thanks to time spent there as a child and, in 1955, he got the chance to work in the city. Employed by Cameli Petroli at the time, he transferred to the Genoa office and began to immerse himself in the local culture. There he not only married a prominent member of Genovese society, Dany Rusca, but found a new team to support.

Mantovani followed Genoa, even signing a two-season ‘subscription’ to the club on the promise of Rossoblu owner Giacomo Berrino that, if enough supporters did likewise, the club would not sell star player Gigi Meroni. But that promise, like those made by so many other presidenti, was ultimately broken—amid mounting debts, Meroni was sold to Torino for 300 million lira. Disgusted by such underhand schematics, Mantovani stopped supporting Genoa, and years later he would work for their fierce local rivals.

By the time he first arrived at Sampdoria in 1973, the club was less than three decades old, and they were decidedly behind Genoa in terms of historic achievement. Mantovani, meanwhile, was branching out on his own in the business world, having founded his own company in the oil industry. For three years he combined running a firm with the role of Sampdoria press secretary, in which he showed a level of ruthlessness not in keeping with the widespread opinion of his personality—it was rumoured that he maintained detailed report cards on all journalists he came into contact with.

Glauco Lolli Ghetti, a man the media dubbed the ‘King of the Seas’ on account of his owning one of the largest fleets in the country, had two separate spells as Sampdoria president in the 1960s and 1970s. But, following relegation to Serie B in 1977, he resigned from his duties. Edmondo Costa stepped in temporarily, but the club desperately needed someone capable of injecting both financial capital and ambition.

As owner of Pontoil, Mantovani, along with partners Lorenzo Noli and Mario Contini, profited greatly during the 1979 energy crisis, and months later he would step in to buy Sampdoria. On 3 July his ownership was confirmed, and a glorious new era in calcio history was officially underway.

Like almost all Italian football club owners, Mantovani came with promises; not only did he want to return the club to Serie A, but he wanted to win a Scudetto. But, unlike almost all Italian football club owners, he kept his promises. And one of the first building blocks toward fulfilling those lofty objectives came with the construction of a new training complex. In what was a clear indication of intent, within the first year of Mantovani’s presidency the Centro Sportivo Gloriano Mugnaini was opened.

There were some difficulties in the early stages of his time in charge, however. From 1981 to 1983, he was involved in a legal case relating to his work with Pontoil that saw him accused of tax evasion, fraud and oil smuggling. Mantovani was eventually acquitted, though he also endured serious health issues during this period. He suffered an acute diaphragmatic infarction during a Coppa Italia defeat to Cagliari in March 1982 and had to fly to Phoenix to undergo heart surgery.

Having survived legal and health scares, Mantovani decided to concentrate fully on Sampdoria, leaving the oil industry. By this point, the first of his promises had already been made good—under the auspices of Renzo Ulivieri, the club achieved promotion having finished third in Serie B behind Hellas Verona and Pisa. And, back in the big time, the calibre of player brought in improved drastically.

Unlike other owners, Mantovani had no ulterior motive. He wasn’t running Sampdoria to boost his reputation or massage his ego, he didn’t use the club as a mask for financial wrongdoing, and he didn’t seek to use his team’s performance as a means to gain politically. Success was an end in itself, and Mantovani’s investment, combined with the scouting and negotiation skills of sporting director Paul Borea, ensured the club was set up to thrive in Serie A.

Over the course of Sampdoria’s first four years back in the top flight, several star names arrived, including Liam Brady, Trevor Francis and Graeme Souness. Borea’s sound recruitment model also involved the signature of top young talent. Roberto Mancini joined from Bologna at 17 years of age, a 20-year-old Fausto Pari arrived from Parma and a 19-year-old Gianluca Vialli was signed from Cremonese. Ulivieri cemented the Blucerchiati’s place in the top half before his successor in the dugout, Eugenio Bersellini, led the side to Coppa Italia victory, and subsequently continental competition, in 1985.

The discreet, paternal image of Mantovani was no façade. While some on the outside suggested the president was spoiling his players, he was in fact gradually building a truly familial atmosphere. It seemed an unwritten rule that those who signed for Sampdoria should not want to leave, even if the big guns came calling. Vialli was particularly complimentary about his former president, writing in ‘The Italian Job’ that, “Mantovani was the classic father-figure chairman, a throwback to another era. He loved the club and saw players, coaches, fans…as members of an extended family.”

Mantovani took a decidedly informal approach to contract negotiations with his players, talking to them directly and often encouraging them not to go for long-term deals with set salaries. Instead, he placed his trust in them, suggesting that pay be re-negotiated on an annual basis. In his own way, he was attempting to foster a culture of constant self-improvement—players knew that, were they to develop year-on-year, they would be rewarded financially. While other presidents treated their footballers as commodities to be bought and sold, Mantovani looked to build relationships with them. His was an approach at odds with the increasing commercialisation of the beautiful game.

In 1986, following a 12th-place finish, Vujadin Boskov was brought in as Sampdoria’s head coach. Experienced and well-travelled, Boskov quickly became a cult hero for his quirky aphorisms and qualities as tactician, motivator and trainer. In his first four seasons at the helm, the club picked up three major honours—the Coppa Italia in 1988 and 1989, and the European Cup Winners’ Cup in 1990. The latter achievement moved Mantovani to suggest Italian football had a new Scudetto contender on the horizon. “Our enemies are not in Genoa,” he said, “[but] in Florence, Milan, (and) Turin.”

With a defence containing exceptionally agile goalkeeper Gianluca Pagliuca and central defensive colossus Pietro Vierchowod, a midfield including experienced Brazilian playmaker Toninho Cerezo, Pari, Attilio Lombardo and Srecko Katanec, and a stunning attacking duet of Vialli and Mancini, it was hard to argue against Mantovani. His methods might have been old school, but the president had nonetheless managed to assemble a squad capable of competing with anyone in Europe. And, between 1990 and 1992, that was exactly what they did.

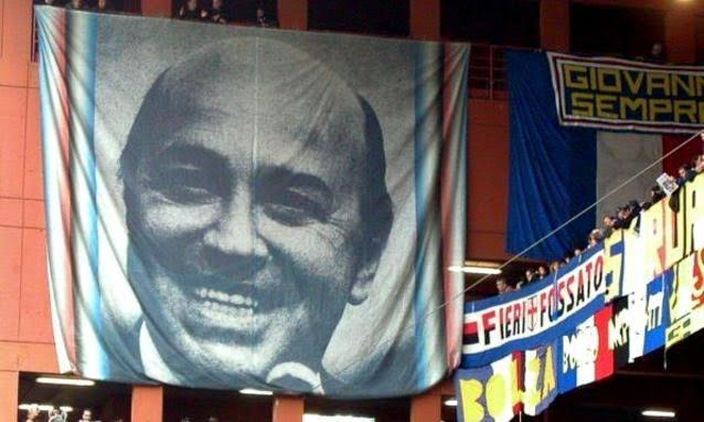

A banner of Mantovani hanging from the stronghold of Sampdoria’s ultras, the Gradinata Sud

First came the Scudetto. In 1991, Boskov led Sampdoria to their first-ever league title. With just three defeats from 34 fixtures, his side finished five points clear of Arrigo Sacchi’s iconic AC Milan. Then, in the 1991-92 season, they saw off the likes of Red Star Belgrade and Anderlecht to reach a European Cup final where they faced Barcelona.

Known as the ‘Dream Team’, Johan Cruyff’s Catalan giants were intent on winning the European Cup for the first time in their long, storied history. The fact that Sampdoria were one win away from achieving the exact same feat less than half a century on from their foundation spoke volumes about both the rapidity and scale of progress under Mantovani’s ownership.

For much of their history, Sampdoria had been Genoa’s second club, lying in the shadows of their venerable city rival’s achievements. Yet, at Wembley Stadium on 20 May 1992, they stood 90 minutes away from becoming the number one side in Europe. A Ronald Koeman free kick put paid to that dream, and Boskov subsequently left, but the Blucerchiati had gone further than anyone could possibly have imagined 13 years previously, when the club languished in Serie B.

High-profile players and managers continued to file in. Sven-Goran Eriksson replaced Boskov, Dutch icon Ruud Gullit signed from Milan, and England internationals Des Walker and David Platt arrived, but another title proved elusive. And, on 14 October 1993, Mantovani passed away following a battle with lung cancer.

With a warm smile and kind eyes, Mantovani respected his team and their fans. In return, he received adulation from both. Yet, rather than hog the limelight, he worked silently in the background. He was no ordinary president; he enjoyed football, loved his adopted city and, helpfully, happened to have money, which he invested astutely in his chosen club.

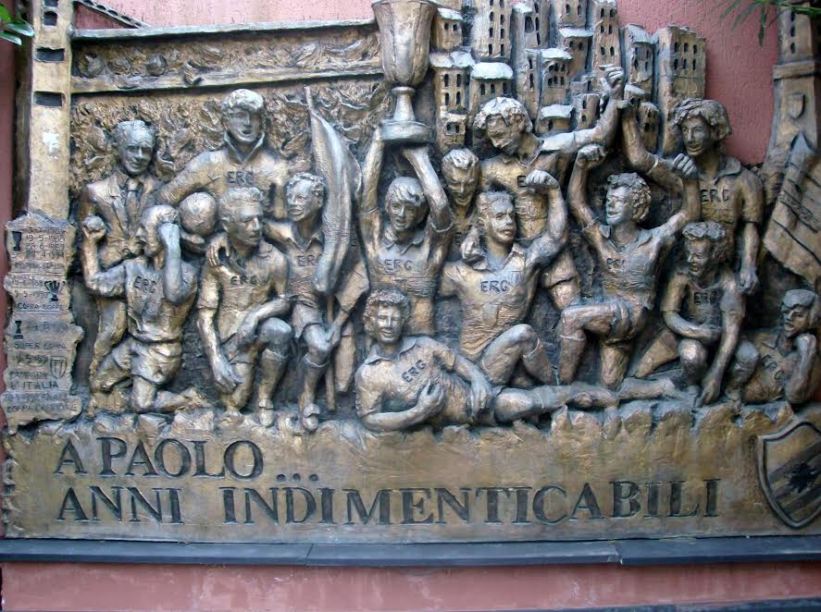

The plaque dedicated to Mantovani at Sampdoria’s training facility – ‘Unforgettable Years’

Like many others who have changed the course of history, there remain visible traces of Mantovani’s legacy. In the city there is a street named after him, while at the training facility he helped to build there is a plaque dedicated to his great Sampdoria team.

The plaque shows his players celebrating with one of their many trophies. Underneath four words are inscribed in capitals. The words simply read: “A Paolo … Anni Indimenticabili.”

“To Paolo … Unforgettable Years.”

Words by Blair Newman @TheBlairNewman

‘Blair is co-editor of The Gentleman Ultra. He is also a freelance football writer for FourFourTwo, uMAXit, These Football Times, and others.’