When a player breaks his leg in a top-flight game, it is never immediately obvious. In the stadiums, you will always get two conflicting views from two decidedly biased onlookers. As one set of fans cry gamesmanship, the opposition supporters rail against the act of battery they have been forced to witness. After a few minutes, when a stretcher is brought on and the strap of an oxygen mask is slipped behind the player’s head, the argument is settled, though rarely the cause.

Watching on television, recognition of the injury’s severity takes even less time. “And this could be bad news for so-and-so” suggests the commentator, as he or she struggles for ways to narrate a prone player. The director will then cue a replay of the incident that, depending on their squeamishness, may get multiple airings. “No one wants to see that” remarks the co-commentator, utterly incorrectly. A YouTube video entitled “The 10 worst leg breaks in football” has over 100,000 views.

Italia Wasteels’ game against St Germains lacks the fans, commentators and cameras of a professional tie, yet it is more immediately obvious that something is very wrong. Unimpeded by the roar of fans, the sound of a bone snapping is terrifyingly loud. Substitute and de facto linesman Vincenzo Gambino rushes onto the pitch, more immediately aware of Domenico Cattini’s injury than perhaps even he is.

An ambulance is called and Domenico, ashen-faced as the blood diverts elsewhere, is kept warm under a mass of coats, propped up on captain Marco Marchini’s shoulder. The game had been full-blooded though not bad tempered, with his broken leg probably best chalked up as “just one of those unfortunate things”.

After a while, once the shock has worn off, Domenico starts making jokes and the players tell me stories of other, often even worse, injuries. There would have been plenty throughout the history of Italia Wasteels. Amongst the players and staff present, all 49 years of the club’s history are accounted for, and most of the thousands of club games were either watched or played by two generations.

Luigi Farnesi calls the ambulance. He is the club’s only ever-present servant, starting the team with his brother in their early twenties and remaining at Wasteels in a variety of roles since then. After nearly half-a-century, this is not the first-time Luigi will have made that call. Indeed, it is not the first time he has had to deal with the broken leg of a Cattini. The club’s meticulous records note that Domenico’s father, Mario, was a “wonderfully skilled attacking midfield player whose career was held back after breaking his leg.

Claudio Marchini, the club’s manager and scorer of nearly 100 goals in the 1970s, brings water onto the pitch. Like Luigi, he has been with Italia Wasteels since the beginning, with his sons Riccardo and Marco now the defensive linchpins of the side.

This is just another twist in the long story of the UK’s sole surviving Italian football club. Along with the broken legs and other misfortune, there have been league triumphs and cup runs, late winners and stoppage time sickeners. It is a rich history, and one inextricably linked to the wider story of post-war Italian migration to England.

The History

A community of Italians in London had been established long before the Second World War, most notably in the “Little Italy” of Clerkenwell, complete with its own basilica-style church. Throughout the 1800s, thousands of Italians would settle in London. Many of the immigrants were artisans, specialists in terrazzo or plaster figure making, whilst others worked in catering, particularly the making and selling of ice cream. Most came from the north of Italy, and by 1939, more than 20,000 Italians lived in the UK.

After Benito Mussolini allied with Adolf Hitler’s Germany in 1940, Italian men of fighting age were arrested and interned in camps around the country, all considered potential enemies of the state. 476 Italian internees drowned after the Arandora Star ocean liner was sunk on its way to Canada, carrying those deemed, often incorrectly, most sympathetic to the fascist cause. Internment had cost many Italians their livelihoods, and some their lives.

Back in Italy, things were even worse. The country had been ravaged by a land war that had all but destroyed its economy. The harsh conditions in the peninsula drove a wave of migration throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s, only later stemmed by Italy’s emergence as a major industrial power.

Though many Italians chose to settle in the New World – Argentina and the USA predominantly – and Australia, some preferred the Old. Of those who moved to England, most were recruited under the European Voluntary Workers Scheme, usually as labourers in heavy industry, before they had residence and choice of work; many were recruited by brick factories in Peterborough and Bedford. However, London was still, as it had been for thousands of Italians for over hundreds of years, the place to be, and most of the post-war recruits moved there as soon as they could.

Robin Palmer is currently a professor of anthropology at Rhodes University in South Africa, but in the 1970s, he was doing research for his doctoral thesis on Italian migrants in London, entitled: ‘The Britalians’: An Anthropological Investigation.

“The accepted term for Italians in Britain at the time was ‘Italianates’, but I didn’t like it because I thought it objectified them” Palmer tells me. “I needed a collective term to include not only the Italian born people, but also their British born children. So I called them Britalians instead.”

Palmer’s work was revolutionary for its time. Rather than regarding the immigrants as sociological problems, as had been the academic norm, he sought to look at where they had come from, as well as the conditions they encountered once they had emigrated. During his research, he found that the relationship between the Britalians and their hosts had been damaged by the war. “The experience of internment, culminating in the Arandora Star disaster …for a small community to lose over 400-men was a terrible thing,” says Palmer.

It essentially took out a lot of the pre-War leadership. They were terribly shocked by the experience of a whole society turning on them through no direct fault of their own, simply because they shared a nationality with Mussolini. They were very cautious after the war. And I think it persuaded people to live in the community.

The community could not revolve around Clerkenwell as it had done previously, and another Italian church was set up, over 100 years after St Peter’s was consecrated. Many of the post-war migrants settled south of the river, where the houses were cheaper. The church was positioned at the heart of that community on Brixton Road. The church was, and still is, run by the Scalabrinian Fathers, an order set up to tend to the needs of the Italian diaspora throughout the world. Palmer found that the order took a broad view of their responsibility to the community.

The Scalabrini were sent as missionaries, but rather than to “convert the natives”, they were sent to retain Italian immigrants for the church. To keep them Catholic, but also to look after their needs, not only spiritual but also material, and even recreational. They might have retreats for the very religious, but then they might have football teams for the youth.

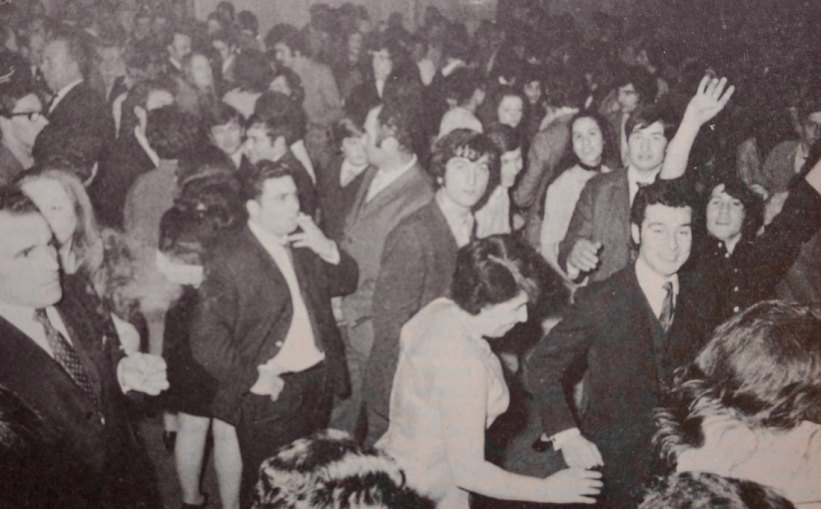

The Scalabrinians thought up numerous ways to keep young and old Italians involved in the community. The best example being Club Italia, founded at the Scalabrini Centre in 1963. An extract of the diary that Palmer kept whilst completing his thesis gives a good sense of what the club was like:

Sunday 22nd October 1972. “This is the first time I have seen so many Britalians together in one place. Either most of the families which belong to Club Italia are here or many members have brought friends. Nearly all the young people are dancing; there are a lot of older women sitting around the edge of the floor trying to talk to each other above Father Silvano’s discotheque and minding the younger children.The other children are dancing or just running around, jumping from the stage. The bar lounge is full of men; some of them around the bar, others in groups playing cards at tables. The other priests are there too, mingling. I watch the way they relate to their parishioners. It is very informal and natural. Father Silvano is surrounded by a group of young people, requesting records, having a go at being disc jockey, or just chatting to him.”

Fun for all ages organised by jocular priests turned DJs for the night, back to the sacraments come morning. The order understood that for the migrants who arrived after the war – desperate to make better lives for themselves and their children in a new country – language schools, cultural events and newspapers acted just as effectively as social glues as the church, if not more so. This was also the driving force behind the creation of the Anglo-Italian Football League (AIFL), made up of teams from London and its outlying areas. Just as Italians were sure to bring mosaic and ice cream, they took calcio with them as well.

Wasteels players partying at Club Italia (Image: Italia Wasteels)

Every fortnight La Voce Degli Italiani, a Scalabrini-run Italian-language newspaper, would print the Serie A table across from that of the AIFL, the Britalian’s pseudo-Scudetto. In the issues from the 1970s, mentions of the great Juventus of Turin are often given second billing to the less famous Juventus of Peterborough, or even the one in Swindon. In 1969, the inaugural Anglo Italian Cup is advertised, but still follows after the more important news of the latest AIFL results.

The league was a major fixture of amateur football in London for several decades. Some years there were close to 20 teams competing for the title, most sponsored by companies with links to the Italian community, like travel agents or catering companies. In 1968, the league expanded to include three more teams, one of which was the embryonic Italia, which would later grow into Wasteels.

Luigi was encouraged to make a team by Silvano Bertapelle, the aforementioned Scalabrian priest and DJ. Both Claudio and Luigi remember him fondly. During the journey back from another game aborted following a broken leg – this time suffered by a member of the opposition – the club’s current custodians reminisce about the Wasteels’ founding Father.

“He was a priest,” says Claudio, “but he was also a friend to us. He used to ask me why I never came to confession, and I would tell him: ‘Father, I see you every day! If I told you about all of the things I was doing you would have to kick me out of the club.’”

Claudio and Luigi are quite different. Where the manager is gregarious and talkative, Luigi, whilst equally amiable, is more reserved. Despite their contrasting characters, they have remarkably similar stories of arriving in England. They both moved to London as teenagers with their parents, and ran coffee shops as their parents had done. Indeed, Luigi still runs one, in the main UCL (University College London) building.

I meet him there during the week, and it is obvious his convivial manner has made him popular with the staff and students. He was 23 when he started the club, supported by Father Silvano and later sponsored by Benedetto Longinotti, who ran the Wasteels travel agency in London. He offers me a coffee and hands me a book printed for the 25th anniversary of Wasteels. Over almost 200 pages, every appearance and goal is meticulously recorded, with an appraisal of each season written by a former coach or player.

Great teammates are remembered. Claudio and his brother Oscar take a paragraph to marvel over the ability of Osman Bayram, who was with the club for a few seasons before he went on to play for Dulwich Hamlet and then briefly for Millwall. Both are certain he could have played for Turkey if he had wanted to. The biggest name, however, is Ray Houghton who turned out for AIFL side Avellino when he was just 13.

Rivalries are recalled and refereeing grievances are cathartically recorded. After mixed results in its first few seasons, Wasteels won the AIFL in 1972, the first of many league triumphs. La Voce Degli Italiani gave a double page spread to celebrate Wasteels’ league and cup double. Hundreds, maybe even thousands, of spectators were there to witness the club beat Libertas in the league final.

The 1972 league final between Wasteels and Libertas (Image: Italia Wasteels)

But after this success, more fallow years were to follow, and it was well over two decades before Wasteels were again crowned champions of the incredibly competitive AIFL. Like many leagues, an influx of money saw other teams with greater resources beat Wasteels to titles. In much the same way as oil riches would ensure the rise of Manchester City and Chelsea 40-years later, the influx of ice cream money would help put Benigra FC top of the league, named after the now defunct Gelateria on Tottenham Court Road.

Though there is only limited success in the league, Wasteels did win the London Junior FA Cup in 1984, a tournament that hundreds of sides across London enter, beating Toby Football Club in the final.

It is often difficult to say whether a Sunday league side could be considered an underdog. After all, one late night for a key central midfielder can be the undoing of any side, and a teammate’s badly timed wedding can decimate even the deepest squad. Judging by the match programme, however, Toby FC had quite the team. The previous season, Toby’s Mark Gerbaldi was playing for Arsenal’s youth team alongside Martin Keown and Tony Adams, and the team’s spine was made up of youth products from Chelsea, Fulham and Brentford.

The Wasteels line-up was decidedly less grand, yet they still ran out winners. Testament to players and management, as well as the strength of Italian football in England at the time; Wasteels might have won the national cup, but they were well off the pace in the AIFL, finishing third. The article in La Voce Degli Italiani that celebrates Wasteels reaching the final is keen to note “that this result is an achievement in itself for the Anglo-Italian Football League in London”.

The only goal in the 1-0 win was scored by John Sidoli, whose father, Guido, was the manager at the time, and who would manage the team himself once he hung up his boots. Though many players were of Italian descent, Wasteels operated with a pragmatic “if you are good enough, you are Italian enough” recruitment policy. For every Gabrielle on the team sheet, there is an Anderson, for every Cattini a McKillop. A vowel at the end of your name helped, but ability with the ball helped even more.

The year 1984 saw the AIFL at the very peak of its powers, so large that it had to be split into two divisions; though the league would decline as Wasteels grew stronger. In 1991, Wasteels left the league altogether; having won it five times in a row, they sought new and greater challenges.

Wasteels continued to be successful, winning a league and cup double in 1996, and another citywide tournament, the London FA Challenge Cup in 1999. Luigi was there for all of these triumphs. He takes me through all the pictures he has kept, including snapshots of Sidoli’s cup winning goal, the team on tour in Italy, and posing for the front cover of Pete May’s book, Sunday Muddy Sunday.

Luigi came to London with his parents from Tuscany, and has worked in coffee shops since he was 14. His accent is definitely one of a Londoner, though laced with the peninsula on which he grew up. Well over half of his life is wrapped up in the history of the football club he started in the Scalabrini hall.

“Me and Claudio took over running the club two years ago, there was a chance that it might die out, and we didn’t want to see 50 years go down the drain.” Every year the team try to get clubmen, past and present, together at a hotel in London for a celebration of the team’s anniversary. “It will be the 50-year anniversary soon” remarks Luigi, “if we get that far.”

The 1984 cup winning side (Image: Italia Wasteels)

The Present

I decided to cover Wasteels after reading about them online, but a month into following them around south London, I was yet to see them finish a game. First there was poor Domenico’s broken leg, then another one for an opposition player. Next there was a team that dropped out at the last minute, and the Sunday after that a waterlogged pitch. I had almost given up hope of ever seeing a match completed.Then, one Saturday evening, I got a text from captain Marco Marchini, asking if I could come the following morning, not just to take pictures and conduct interviews, but to play. I agreed and turned up at half nine to replace Marco’s brother, Riccardo, a tall defender with great feet who was away at a wedding.I was quite pleased to get the chance in a way. My grandfather moved from Friuli to Ireland shortly after the war, and I felt that playing for the team was a fulfilment of my responsibilities to the wider diaspora. I slot in at centre back for the cup tie, ready to hold the fort and eager to play my part in Italia Wasteels’ illustrious history.

We lose 8-0.

Marco struggles to find words to articulate his annoyance. The team is cobbled together last minute, with injuries and other commitments taking its toll on a small squad. In a way, it is a wonder there are eleven players at all, and Marco is reticent to attack those who have done the team the favour of turning up. He references the proud history of the club and gestures to Luigi, who is somewhat less worried about lambasting us. “Lu started this club 49 years ago, and he is here every week” says Marco.

The secretary is busy stuffing dirty kits into a bag, and mutters “It is weeks like this that make me wonder why I bother.” I myself wonder whether this game is more or less of a disaster than the ones that ended with broken legs. This game sure as hell feels worse for me, though I think that Domenico, still on crutches, might disagree.

In truth, the result is an anomaly and not indicative of the season. The team has definitely had some bad luck, and although the club is in the wrong half of the table, there is good reason to think that they won’t be relegated. When a full team is fielded, they are quite the proposition. The Marchini brothers are resolute in defence, their cousin Damon is a tricky winger, and in midfield, Reda Barouti and Darren Anderson (one of the very few non-Italian second generation Wasteels players) are more than capable of holding the team together.

The problem is not so much with the core personnel, as it is with them turning up. Claudio does remark that it would not have been so in their day. “Back then we had the football and Club Italia. That was it. We may not have had a lot of money, but we would spend it on petrol to travel to Peterborough, Woking or Bedford every week.”

To be fair to the current cohort, part of this is just representative of the way that Sundays have changed. When Luigi and Claudio were driving to games in the 1970s, they would have had much of the road to themselves; shops weren’t allowed to open, and the working week was more clearly defined between Monday and Friday. After all, Italia Wasteels is hardly the only Sunday league team in the country scrabbling around for players on Saturday night, it was just the only one unfortunate enough to call on me.

The team also has a fair few new arrivals from Italy. Along with the second and third generation Italians in the team. Goalkeeper Valentino Ciciarelli is from Rome, Vincenzo Gambino has moved to London from Sicily and midfielder Andrea Morisco was born in Naples.

Current captain Marco Marchini in action for Wasteels during a league game (Image: Gianlucca de Paoli)

Dr Giuseppe Scotto is a researcher at John Moore’s University in Liverpool, and has looked closely at the differences between post-war migrants like Luigi and Claudio, and their modern-day counterparts. He discovered that the old and new migrant groups have surprisingly little to do with one another. “In my study,” Scotto tells me “I distinguish between people who arrive after World War II up until the end of the 70s. Then in the 70s, immigration from Italy decreased. I considered the new wave that began in the 80s, but became more significant in the 90s and boomed in the past few years.”

Whereas the community fostered by the Scalabrini and similar organisations had meant so much and been so important to many Italians in London, the new type of migrant from Italy is less reliant on these institutions. Much of this is down to alternatives offered by technology, as Scotto explains:

Facebook and other social media [outlets] can satisfy some of the needs that migrants traditionally have. On many of the groups there are requests for information, about what paperwork you need to get a job. Often there are requests from those who are still in Italy but are considering moving.

Italia Wasteels are one of the few remaining relics of the Italian community that once thrived. La Voce Degli Italiani stopped printing in 2011, the travel company from which Wasteels take their name no longer operates in England, and the AIFL is long gone, its final season concluded over a decade ago.Despite these closures, the Scalabrini church is still at the same place on Brixton Road, offering mass in Italian several times a week. Club Italia also continues, though it is less popular and raucous than when Professor Palmer was doing his field work there. “Club Italia is now for the elderly,” says Katia Bortolazzo, the church’s secretary. “Back then they were not so elderly and they are the same people [who would have come in the 1970s]. So now we tailor it for them, as a social platform.”

Whilst I was at the Scalabrini centre, scouring old issues of La Voce Degli Italiani for news of Wasteels’ long concluded LFA Cup run, two teenagers were working next to me, sent to London in order to improve their English. Bortolazzo says that this is a big part of the reason Italians come over nowadays, and that they tend not to settle in the same way as the post-war generation. Additionally, those who do settle are less likely to rely on the community the Scalabrini offer, some which Scotto again expands on:

Don’t forget that those who came before may have spent years before returning back to their land. There is not the same desire to spend time with those from your country, when it is so much easier to just travel back [to Italy]. Travelling then would have cost a fortune, and they were not very well off of course, that is why they were here trying to build a better future.

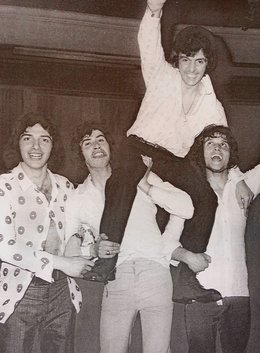

Luigi held aloft after Wasteels league victory in 1972 (Image: Italia Wasteels)

Luigi held aloft after Wasteels league victory in 1972 (Image: Italia Wasteels)

In his preface to a book celebrating Wasteels’ 25th anniversary, Luigi gives much the same reasons for the importance of the community the Scalabrini have created: “The social club was a focus point for the younger generation which met, enjoyed each other’s company and reminisced about the land they had all left to emigrate to England, each for their own reason, and for having to leave so many loved ones behind.”

The overall impression is that for those of Luigi’s generation, the community was more important than it is for those Italians who play in the team now. This is natural given the ease with which these Italians can return home, as well as the comparatively inexpensive communication they can have with family and friends back in Italy.It is also important to remember that Italy has changed. As Scotto puts it “[The Old and New migrants] come from two different Italys. People who left Italy 40, 50, or 60 years ago, had a completely different view of Italy and Italians than those who have moved more recently.”Migration to the UK, and from Italy more generally, declined after the unexpected transformation of the country’s economy in the late 1950s, so unexpected that it was referred to as il miracolo economico. Though there is still a huge and widespread Italian diaspora, the improved economic situation in Italy has meant fewer Italians are forced abroad to make a living.Whereas Italy was once a country that might send over 800,000 migrants abroad a year, it now finds itself at the heart of a different migrant crisis, with thousands making perilous and often fatal journeys to a country that Luigi and Claudio’s parents had left in desperation. The Scalabrini order still work with migrants, but often they are those arriving on the shores of Sicily, rather than those leaving it. The order’s church in London conducts Mass in Portuguese, as well as Italian, to cater to the large population of Portuguese immigrants in south London, that now dwarfs the Italian counterparts in that area.The AIFL could not exist today. Many of the travel agents and catering businesses that once sponsored the teams are gone, or have moved away from the Italian community. In one way, this is a very good thing. The Italians are now more integrated than ever before, with new arrivals less suspicious of their hosts. The descendants of the post-war migrants have embraced an English way of life, their surnames adding a little continental glamour to pub teams across the country.

Still, of those Italian clubs that formed in the 1960s, it is heartwarming to know that one survived. Testament to the hard work of generations of Sidoli’s, Anderson’s, and Marchini’s. Luigi in particular has shown a remarkable dedication to a club he started almost half a century ago. Though my visit coincides with a difficult period for Wasteels, what with all the broken legs, they still win several of the games I attend, though none of the ones I play in. Merely coincidence, I am sure.

Wasteels take the first 3 points of the season against @greencourt with an impressive 3-1 win! One goal from Lorenzo and 2 from Lee seal it! pic.twitter.com/hQaMpz0Ioi

— Italia Wasteels F.C (@WasteelsFC) October 9, 2016

Wasteels has outlived every other Italian team, continuing to offer Italians a chance to speak their language on the weekends; a relic of a time not too long ago, when the calciatori ruled London’s Sunday league football. As such, there is one team still befuddling opposition centre forwards with Italian instructions from centre-back to goalkeeper.

During another game I play in, one such confused striker looks up after Marco shouts something at Valentino. He asks the captain, dressed in blue with the tricolore on his breast, “Are you lot fucking Italian or something?”

“Yeah,” Marco replies, “something like that mate.”

Words by Gianlucca de Paoli: @ManySundays

‘Gianlucca is a blogger and journalist, currently writing about teams in the UK made up of migrants.’

You can also follow Italia Wasteels on Twitter: @WasteelsFC