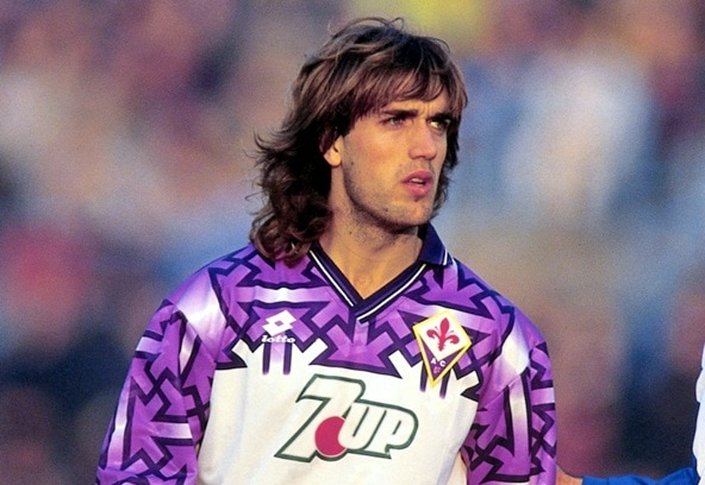

“Batistutaaaaa!” yelled the great Peter Brackley seemingly every other Sunday afternoon. It was one of the most striking visuals in any sport of the 1990s, the Argentine front man wheeling away in celebration, his golden locks flowing majestically whilst in the purple of Fiorentina, accompanied by Brackley’s commentary. To people of a certain generation, the memory of Gabriel Batistuta destroying defences the length and breadth of Italy will give them a warm, fuzzy feeling.

Batistuta was a sight to behold when in full flow. In a period littered with top of the range strikers, he was head and shoulders above the rest. If one was to compare Batistuta to a horse, he was the embodiment of a thoroughbred. A one-man stallion trampling over the carcasses of world-class defenders on a weekly basis.

By the beginning of the 1995-96 season, Batigol had been at Fiorentina for four years and had already amassed an impressive 55 goals in 91 Serie A games. Showing tremendous loyalty, he had plundered 16 goals to guide La Viola out of the doldrums of Serie B at the first attempt after their shock relegation in 1992-93.

Upon their return to the top flight a year later, Batistuta would be crowned Capocannoniere with 26 goals, the result of a blossoming relationship with a young Manuel Rui Costa. Fiorentina finished the 1994-95 campaign in 10th position under current Leicester City boss Claudio Ranieri, but the ever-ambitious president Vittorio Cecchi Gori wanted further improvement.

By his lofty standards Batistuta had a slow start to the season as he failed to find the net in the opening four games, however he would soon rectify this tardiness and the goals started racking up. Four braces against Lazio, Torino, Udinese and Atalanta with further single strikes against Cremonese, Bari, Inter, Padova, Roma and Vicenza saw him race up the scoring charts. By February of 1996 he had 14 goals in the league and a further two in the Coppa Italia. ‘El Rey Leon’ (The Lion King) was frothing at the mouth for more teams to chew up and spit out, and at the end of the month Napoli travelled to Florence.

Napoli, by the mid-1990s, were slowly sinking towards the end of a near decade-long decline. The days of Diego Maradona strolling around the San Paolo and slaying the giants of the north were nothing but a distant memory by 1996. Whilst Marcello Lippi did bring some respite in 1993-94 when the Partenopei finished a credible sixth, the post-Diego years had been volatile. Challenging for the Scudetto was no longer the agenda; mid-table mediocrity was now the name of the game.

The legendary Vujadin Boškov, formerly Sampdoria’s coach, had taken charge of the side midway through the previous season and had managed an upswing in results, finishing in 7th place. Despite the positive second half to the campaign, star player Fabio Cannavaro had been sold to Parma and was replaced by the rugged-yet-exceptional Roberto Ayala. Yet a look through their squad for 1995-96 shows a ragtag team filled with either journeymen players or youngsters with potential. Not a single superstar in sight.

When the pair met first met in October, Batistuta’s men triumphed with a 2 – 0 win. When they next came together in round 23 of the season, Fiorentina were second in the table, seven points behind runaway leaders Milan and a point ahead of Parma. Napoli meanwhile were sitting comfortably in 10th position and, while scoring was a problem – they had only found the net 22 times – their defence was almost watertight relative to their position in the table, conceding only 26 goals. To give a comparison, Atalanta – only three places behind Napoli – had conceded 35 goals.

If ever there was a goal in his extensive back catalogue that typified the very essence of what Batistuta possessed as a striker; frightening power, a towering physique and strength, pace and a simply unstoppable shot, it was his second goal of this match.

Click to read ‘An Undying Love Affair, Argentines in Italy: Gabriel Omar Batistuta’

The Argentine had toyed with the away side all afternoon. He and partner Francesco Baiano, superbly nicknamed Ba-Ba by the Italian media, were pulling the feeble Napoli defenders in every direction. Baiano is a somewhat underrated player in his homeland, possessed with a glorious turn of pace and incisive vision, he only ever received two caps for Italy, and both came whilst playing for Foggia in the earlier part of the decade. He’d played alongside Batistuta since 1992 and this would be his most productive season in purple as he scored 11 times. A year later he would move to Derby County, amongst the first wave of Italians to try their hand in England, where he became a cult hero of sorts.

Batistuta had scored a sublime free-kick late in the first half, a facet of his game that is rather overlooked, and really should have added a second after performing a gorgeous give and go with Baiano that sent him through on goal, but his effort was tame by his ferocious standards.

In the 76th minute Batistuta would rectify this by netting his second. Fiorentina intercepted a Napoli attack and began a charge of their own towards the other end of the field.

Michele Serena races down the right hand side of pitch entering Napoli’s half. Serena has only Baiano ahead of him, who is being tightly marked by two defenders, whilst Batistuta is level with him but in a more central position. The right-back lifts his head and sees that the No.9 has inexplicably been given a clear path to goal, with all of the Napoli defenders occupied with Baiano and committing the cardinal sin of following the ball.

Batistuta is now running straight towards the goal, however the ball takes an odd bounce just before Serena attempts to pass it, making it slightly more difficult. The unexpected bounce actually works in his favour as he brilliantly lofts it with his instep over the heads of the defenders, and the ball arcs beautifully towards the onrushing Batistuta.

The Argentine, now running at full pelt, anticipates the pass by jumping just a fraction; he takes the ball under control by violently cushioning Serena’s pass with his chest whilst simultaneously pushing it onwards. The execution of this alone would have marvellous, but what happens next is typical Batistuta.

Zeroing in on the Napoli goal and with their defenders collectively realising their serious error of giving him an ocean of space, they desperately backpedal, but it is too late.

With both ball and man just inside the D and still running at the speed of a locomotive, Batistuta, with his second touch of the move, cannons the ball past a truly helpless Giuseppe Taglialatela and into the roof of the net.

There is a raw, visceral beauty about the goal. Roberto Baggio was famous for delicately placing the ball in the corner of the goal; Batistuta couldn’t have contrasted more with The Divine Ponytail. If Baggio killed them softly, Batistuta bludgeoned them to death. This was a goal of pure, almost animalistic rage, a beautiful torrent of anger; it was vintage Batistuta.

Fiorentina would add a third goal, Batistuta turning provider for Baiano to secure a comprehensive 3-0 win. They would tail off in the final part of the season, finishing a disappointing fourth. However they would taste glory, beating Atalanta over two legs – with Batistuta of course scoring in both legs – to win the Coppa Italia and thus qualify for the Cup Winners’ Cup. Batistuta would add another brace against Padova in a ridiculous match that ended 6-4, finishing the season on 19 league goals. Ranieri would last a further year at the Artemio Franchi before getting the axe in the summer of 1997.

Napoli survived relegation, finishing in 12th position. Their lack of goals highlighted by the gloriously named Arturo Di Napoli being the team’s top scorer with a paltry five goals. But the downturn wouldn’t be reversed and they would finish 13th the following season before finishing rock bottom in 1997-98, completing their transformation from Scudetto winners to Serie B inside eight tumultuous years.

“Bati was a powerful player,” spoke Ranieri of his former striker. One could argue there hasn’t been one as powerful since Batistuta’s departure from Italy in 2003, some 183 Serie A goals later.