If there was ever a transfer that kick started a mini pop culture revolution, it was Paul Gascoigne’s move to Lazio, 25 years ago this summer.

It’s a well-worn tale by now; England’s finest talent in a generation was signed for an ambitious Lazio side fuelled by Sergio Cragnotti’s money. Gazza’s arrival on the peninsula started a chain of events that ultimately led to Channel 4 buying the TV rights to Serie A for three seasons, paying a paltry £2.5 million in the process and giving rise to AC Jimbo and millions of followers every single week, even if Gascoigne’s time in Italy wasn’t the success story everyone initially hoped it would be.

Yet it doesn’t make the story any less true, or important. Gazza’s move was the catalyst for every foreign league that is now broadcast on British television. Serie A, La Liga, Bundesliga and all the various leagues owe a sizeable portion of gratitude to Gascoigne’s Italian adventure. Without him, this website wouldn’t exist, and likewise this piece. Channel 4 – and by extension Gascoigne – wetted our appetites in looking further afield for our football fix. The humdrum of early ‘90s English football simply wasn’t cutting the mustard; we wanted a more sophisticated, a more elegant, and a more cultural style of football.

Gazza emerged from the 1990 World Cup as one of Europe’s brightest stars. His performances, instrumental in England surpassing all expectations and reaching the semi-final, combined with his tears following a second tournament yellow card, ensured that he won the hearts of a nation who had fallen out of love with the game following a brutally dark decade.

Gascoigne had piqued the interest of the biggest European clubs and it was Lazio who first made contact with Tottenham in the spring of 1991. Gascoigne was in the midst of the best season of his career (and with hindsight, his last) and the Roman club had agreed a fee of £8.5 million for the 23-year-old.

Gascoigne then scored a sublime thirty-yard free kick against North-London rivals Arsenal in the FA Cup semi-final as Spurs booked a place in the final. Whilst Lazio and Tottenham had both agreed on a deal, the player refused to sign on the dotted line until their cup run ended. But, with the final against Nottingham Forest on the horizon, and signing for the Biancocelesti just a mere formality, it appeared Gazza’s career was on an ever-increasing trajectory, a player truly destined for greatness. As history would play out, this was to be its pinnacle.

In the showpiece final, he committed the infamous horror tackle on Gary Charles 15-minutes into the game. Outrageously attempting to win a tackle in a situation that massively favoured Charles, he lay writhing in agony on the Wembley turf. Tests would later confirm Gascoigne had ruptured cruiciate ligaments in his right knee. His life would never be the same again.

Lazio quickly hurried to renegotiate the deal, realising that such an injury – especially in the early ‘90s – amounted to nothing short of a death sentence for a player’s career. With Gascoigne facing a lengthy lay-off, a second deal was rehashed, for £5.5 million.

Gascoigne’s road to recovery was laborious; he reinjured the knee in a nightclub brawl in late 1991, as Lazio anxiously looked on from afar. The incident was a precursor to what lay ahead for the club in the following three years.

His debut would come, finally, in late September 1992, in a 1-1 draw against Genoa. He only played 45-minutes, failing to make it out for the second-half after a typical-of-the-era challenge from an overzealous defender. “I went down like a sack of spuds”, Gazza said characteristically.

Despite his absence on the pitch for well over a year, ‘Gazza-mania’ hadn’t lost any of its lustre with British public. An estimated 3 million people, more through curiosity than a profound knowledge of the league, tuned into watch the first offering of Channel 4’s Serie A coverage. What they got was a thrilling 3-3 draw between Sampdoria and Lazio that didn’t feature Gascoigne, not yet match fit. The game was an end-to-end affair that included two own goals, a brilliant free-kick from Samp’s Vladimir Jugović and a pair of Beppe Signori goals. The bar had been set. A nation hooked.

Lazio were in their third season under the tutelage of goalkeeping great Dino Zoff. They had lost their chief goal-scorer – and future best friend of Dennis Bergkamp – the diminutive Ruben Sosa, to Inter. However, Gascoigne’s new side contained no shortage of talent, from Giuseppe Favalli at the back, to seasoned internationals Aaron Winter, Thomas Doll and Diego Fuser in midfield, and Signori and Karl-Heinz Riedle in attack.

Gazza (right) gets friendly with his teammates on the bench, while Zoff (left) watches the game, characteristically smoking a cigarette

The 1992/93 season was a surreal time in European football, the abolition of the back-pass rule, so often the safe haven for technically limited defenders, ensured absolute chaos in games across the continent, and Serie A was no exception

Some of the score-lines between Italy’s top teams bordered on the ludicrous; week two produced a Pescara 4-5 Milan game, and week three saw Fiorentina obliterate Ancona 7 – 1. However, week five entered into the scarcely believable; Pescara again on the end of a battering, this time by Udinese in a 5-2 loss, Genoa and Ancona played out a 4-4 draw, Gazza’s Lazio beat Parma 5-2 and the truly insane encounter between Fiorentina and Milan that ended 3-7. In ultra conservative Italy of the early ‘90s, this was total anarchy, defensive organisation gone askew.

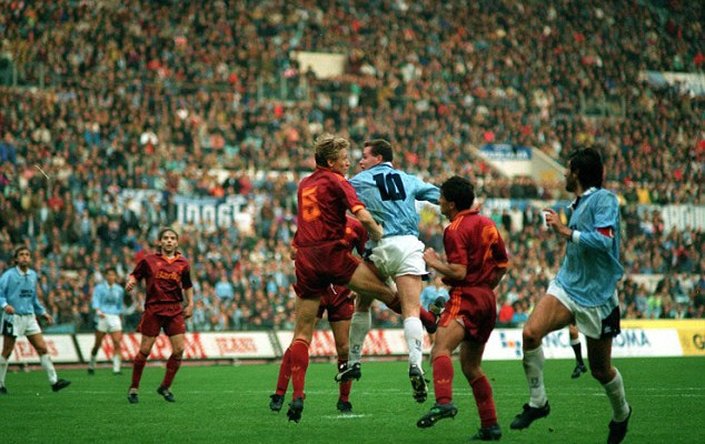

By the time Lazio and Roma met for the derby in late November, Lazio had only won two games from ten. The pressure was starting to mount on Zoff. Roma were similarly in a bad patch of form under Vujadin Boškov, winning only one match more.

Gascoigne started in midfield, alongside Doll, Winter and Fuser. Due to the three-foreigner rule in those pre-Bosman days, this meant consigning Riedle to the Tribuna Monte Mario. The pint-sized yet-lethal Signori up front on his own.

The first-half was back and forth without either team exerting dominance over the other. However, two minutes into the second-half, the Romanisti were sent into the raptures through their Prince; Giuseppe Giannini.

Now sadly overshadowed by Francesco Totti’s seemingly everlasting endurance at the top level, Giannini was the poster boy for all Roma fans throughout the 1980s and early 90s’. Like Totti, Giannini was a number 10 who graduated through the youth system. By 1992, however, he was at odds with totalitarian boss Ottavio Bianchi, and an exit looked likely.

However, Bianchi was the one to be shown the door, and so Giannini was reinstalled to the side and regained the captain’s armband, a situation not so dissimilar to what Totti would go through several years later, with eerily, another Bianchi, this time Carlos.

Giannini pounced to slot the loose ball into the Lazio net following several misjudgments from the Lazio defenders and goalkeeper.

Lazio, knowing a defeat to their local enemies would cause nothing short of a riot, pushed forward and Fuser, always a crisp striker of the ball, unleashed a furious thunderbolt that smashes off the underside of the bar and bounced out.

With four minutes left on the clock, Lazio win a free kick on the left side of the Roma half, some 35 meters from goal. Gascoigne initially ventures over to take the free kick, but after insistence from Signori – who rightly points out that standing at 5ft 7in, he wasn’t going to win many headers – Gascoigne runs back into the box.

Signori stands over the ball and sends an inviting high cross into the box. Gascoigne, who had won several aerial duels throughout the course of the match, rises above a Roma defender to meet Signori’s cross with the side of his head… cue absolute pandemonium in the Stadio Olimpico as the ball nestles in the Roma goal.

Broadcast live on Channel 4, the importance of the goal is accentuated by the majestic (and criminally underrated) Peter Brackley, who gloriously yells “Gascoigne…YES!! He’s got it!! The saviour has saved Lazio!” through his headset. Gazza at first isn’t sure what to do, and then shifts gears, immediately running over to the Curva Nord and is soon mobbed by teammates.

Lazio players bury Gazza under the Curva Nord after his famous equaliser against Roma

Some 561 days had passed since Gascoigne’s last competitive goal. In an intriguing statistic; his final goal for Spurs was in a derby, and his first for Lazio was in a derby. A big game player.

The man himself was under no illusions to what the goal meant to the Laziale and on his trot back to the halfway line he began to cry on Italian soil, again. This time for very different reasons, “I wasn’t crying for joy, more for, phew, thank God for that,” he would later say. “It was the first time in my career I had been nervous in a game, I’ve got to win this game.”

Recalling his derby experience, Gazza said, “I’ve played in some derbies, up in Glasgow as well, but that one (Lazio-Roma) just wasn’t normal. The players from both sides were nearly crying because there was nowhere to run or hide for the losers.”

No matter what was to become of his Lazio career, Gascoigne knew a dramatic late equalizer in the derby would forever forge an eternal bond with the blue half of the Eternal City. “I could live off that goal for a few years over there,” Gascoigne jokingly said.

In 2012, nearly two decades to the day of the goal, Gascoigne returned to his old team when Lazio were pitted against Spurs in the Europa League, and received a hero’s welcome as he did the obligatory lap of honour around the Olimpico.

“Welcome back Gazza. Lionheart, headstrong, pure talent, real man: still our hero,” hung a banner from the Curva Nord.

“I loved that boy,” Zoff said when reflecting on his time with Gascoigne. Thanks to his equaliser in the Derby della Capitale, the Lazio fans will forever love him also. Truly eternal.