In 1976, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak founded Apple, the Concorde completed its first commercial flight and the first movie of the Rocky franchise was released. In football too, it was time for change. The totaalvoetbal revolution inspired by Ajax and Holland spread across the continent as teams, with various degrees of success, tried to follow the example of the great Rinus Michels.

The wind of change and innovation swept across Italy too, as the newspaper La Repubblica – now one of the country’s most respected publications – was launched and school term began on 1 October for the final time. The country’s football landscape witnessed a momentous shift of its own, as Luigi Radice steered Torino to their first title since the Superga disaster 27 years earlier, pipping cross-town rivals Juventus to the Scudetto by two points.

After his men drew their last game of the season 1-1 at home to Cesena, however, Radice looked as gloomy as he had done at any stage during the 30-match campaign. Followed onto the pitch after the final whistle by a group of journalists and a TV camera, he quickly addressed one of his players: “Jesus, I’m really gutted. You’ve let yourself down a bit, lads.”

Torino had won all their home games up until then and the draw spoilt what would have been an otherwise perfect record. In an era when smart phones were still three decades away and when football fixtures were not spread over the weekend, fans inside the grounds relied on transistor radios to keep up to date with the scores. In Italy, however, coaches were forbidden from carrying one themselves, meaning when Radice strode onto the pitch, he still did not know who had secured the title.

The uncertainty would last only for a few seconds, before a journalist puzzled by his reaction broke the news to him. “Aren’t you happy? Juventus have lost, you’ve just won the league,” he said, hugging the Torino head coach.

Radice’s reply was typically understated. “Have they? Well I’m a bit disappointed, though. I mean we’ve thrown a 1-0 lead away,” he said without even managing to break into a smile.

The reaction belied the man’s perfectionist nature.

Radice was a man ahead of his time and he played a pivotal role in carrying the torch of the Dutch revolution to Italy, a place where conservatism was as central to football as the players themselves.

By the time he arrived in Turin in May 1975 to replace Edmondo Fabbri at the helm of the Granata, his managerial career was already entering its second decade, even though he was still a few months short of his 41st birthday. Two spells at Monza either side of a season with Treviso had offered only a glimpse of Radice’s managerial talent, but by the time he steered Cesena to their first ever promotion in Serie A at the end of the 1972-73 campaign, a number of suitors had come knocking.

A season each at Fiorentina and Cagliari – which ended with a sixth and 10th place finish respectively – followed before his arrival in Turin. A promising young tactician and an ambitious side – Torino had never finished lower than sixth in the previous four seasons and had finished runners-up in the 1971-72 season – looked the perfect match.

The honeymoon, however, appeared destined to be short-lived. A few disappointing results in pre-season friendlies, coupled with Radice’s decision to sell veterans like Aldo Agroppi and Angelo Cereser soon attracted criticism from media and fans.

More worryingly, Radice’s style of football came under scrutiny after the Granata managed only one win in their first three league games of the season. For a man who had played under Nereo Rocco, one of the masters of Catenaccio at Padova and AC Milan, Radice’s tactical approach could not have been more different from that of the man they called El Paron.

While Rocco’s teams placed great emphasis on not conceding, pressing and attacking football were central to Radice’s philosophy.

Click to read ‘Nereo Rocco: The Master of Italian Football’

It would take a while, however, for his players to embrace his tactical mantra. Once they did, however, the rewards were immediate, as Torino won nine matches out of a 13-game unbeaten streak stretching from early November until mid-February.Their once spluttering engine now operating at full revs, Torino swarmed over their opponents almost at will. Radice’s men were the first to introduce high pressing in Italy and the first to rely heavily on players moving without the ball and one-touch football. A modern side, which clearly drew inspiration from the Dutch philosophy exported by Ajax and their total football, they took Serie A by storm.

Patrizio Sala, Renato Zaccarelli and Eraldo Pecci, one of Radice’s summer signings, dictated the tempo of the game in midfield, with moustachioed captain Claudio Sala the chief provider for the two strikers, Paolo Pulici and Francesco Graziani. The Goal Twins, as they were known, plundered in 21 and 15 league goals respectively, developing an almost telepathic understanding with each other.

Despite their unbeaten run and their exciting football however, by mid-March Torino still trailed Juventus by five points, a sizeable gap in the two points per win era – Italy would introduce the three points rule only in 1994. Within three weeks, however, the Granata had claimed the local bragging rights and, more importantly, top spot.

Wins against Roma and AC Milan coupled with Juventus’ defeats against Cesena and Inter either side of a 2-1 win in the Derby della Mole – which would then be converted into a 2-0 win, as Juventus were punished after a firecracker launched by their fans exploded next to Torino’s keeper Luciano Castellini – put Radice’s men a point clear.

They would not relinquish their lead, clinching Torino’s seventh – and so far last – league title and ending the season with the best attacking and defensive record. The following season Radice led Torino in the European Cup, a competition he had won as a player with AC Milan less than two years before a serious injury curtailed his career, for the first time in their history.

There was to be no fairytale in Europe, however, as the Granata were knocked out by eventual runners-up Borussia Monchengladbach after losing 2-1 on aggregate and ending the second leg three men down and with Graziani in goal.

On the domestic front, reality was even harder to stomach, as Torino finished second, a point behind Juventus. Radice’s men had accumulated five more points than in their title-winning campaign and improved their record at both ends of the pitch, but to no avail.

Another second place finish followed, this time alongside Vicenza, before Radice, who in 1979 had miraculously escaped a serious car crash which killed his friend Paolo Barison, was relieved of his duties during the 1979-80 season with Torino perilously close to relegation.

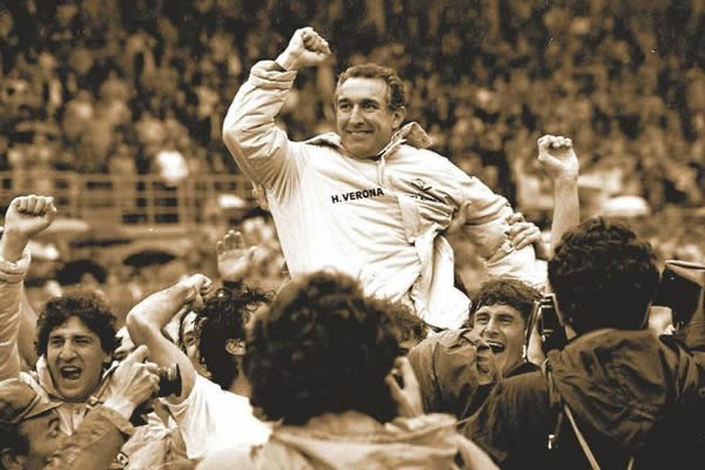

After spells at Bologna, Bari and on both sides of the divide in Milan, Radice returned to Turin in 1984 and looked to have taken the glory days back with him. However, the dream of a fairytale homecoming was dashed by Osvaldo Bagnoli’s Verona, who would write a piece of history of their own by securing their first, and so far only, Scudetto.

Read ‘Miracles Happen: Osvaldo Bagnoli, Verona and the 1985 Scudetto

Radice’s second spell on the banks of the river Po petered out and he left Turin for the final time in 1989, before embarking on another tour of the peninsula’s dugouts. Stints at Roma, Bologna, Fiorentina, Cagliari and Genoa were followed by one final stop at Monza, where it had all begun and where, in 1997, it all ended.

Away from football, Radice lived his retirement as he’d lived his career, eschewing publicity and interviews. When his name was reappeared in the media, it sadly did so for the wrong reasons. In 2015, Radice’s son, Ruggiero, revealed the former Torino manager had developed Alzheimer’s disease over the previous five years.

With a few notable exceptions, Radice, his son said, had been forgotten by the world of Italian football even before his debilitating illness. However, for his 80th birthday, he received a Torino shirt signed by the current players and he will always have a special place in the hearts of the Granata fans.

Those who were kids when he led Torino to the title now have kids and families of their own, but they can still recite the starting XI from 41 years ago like a well-rehearsed mantra, such is the delight that team brought them.

As far as legacies go, it’s hard to think of one that would make Radice prouder, for joy had always been at the centre of his credo.

“I was captured straight away by total football and I’ve always tried to make that philosophy mine,” he once said.

“It’s a risky style to adopt and it’s hard to implement but it’s incredibly easy on the eye. And it fills you with joy.”