Italian clubs have broken the world record for transfer fees 18 times in the modern era, more than those of any other country. During Serie A’s golden years between 1987 and 1992, Juventus and AC Milan seemed to be in a league of their own, breaking each other’s records five times.

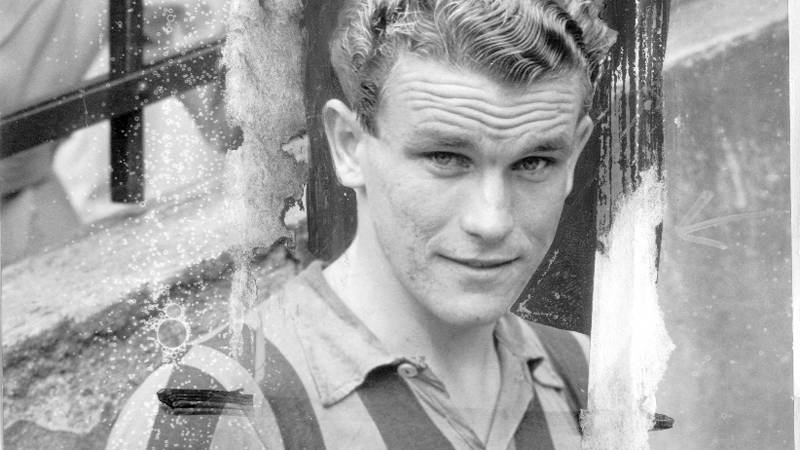

The list of players who have been subjected to world record transfers involving Serie A clubs include luminaries like Diego Maradona, Roberto Baggio, Ruud Gullit and Ronaldo. In this list the name of Hans ‘Hasse’ Jeppson will be recognized by very few calcio fans, even though the player was a pioneer. It was this Swedish striker who set in motion the wheels of gregarious spending by Italian clubs when Napoli broke the bank to sign him from Atalanta.

Jeppson was born on 10 May 1925 in Kungsbacka, Sweden. He started his career with local club Kungsbacka IF before joining Gothenburg-based Orgryte IS in 1946. A curious chain of events would land him at his next club, a turning point in his career. Djurgardens had been relegated from the top tier in 1948 and after season’s end the team went on a tour of Iceland, USA & Canada. Jeppson was included as part of the touring group largely due to his record of scoring 48 goals in 30 matches with Orgryte.

Fascinatingly, Djurgardens took part in what could easily be termed as a precursor of modern era friendlies played in the USA, taking on Liverpool in Brooklyn. Liverpool fielding the legendary Billy Liddell and won 3-2, but Jeppson impressed for the part timers, scoring both of their goals. His 21 strikes on the tour convinced Djurgardens’ management to enlist his services for 1948/49 season.

Under the watchful eyes of coach Per Kaufeldt, himself an ex-star striker and AIK’s all-time top scorer, Jeppson became one of the most lethal finishers in Sweden. Powered by his goals they soon broke into Allsvenskan, and in his three seasons with Djurgardens, Jeppson scored a remarkable 58 times in 51 matches, winning the Allsvenskan top scorer award in 1951 with 17 goals. His scoring prowess soon earned him the nickname of ‘Hasse Goldenfoot’ as he was hailed as natural successor to Gunnar Nordahl for the national team.

Jeppson had debuted for his country in 1949, scoring once as Sweden sealed a historic 3-1 win over star-studded England. He soon got a taste of the big stage by participating in the 1950 World Cup. Sweden came into the World Cup as a team to watch out for thanks to a brilliant performance in their gold-winning Olympic campaign two years before. However, the national team had also lost a string of players including Nordahl and Nils Liedholm due to rules stating that only amateurs could represent Sweden. Unperturbed, coach George Rayner drilled the team hard, especially focusing on Jeppson’s finishing and turning him into a more clinical striker.

Their first opponents in Group 3 were the defending champions, Italy. Gli Azzuri were still reeling from the shock of Superga, but nonetheless had a reasonably strong team and raced into a 1-0 lead after just seven minutes. On the 25th minute Jeppson made it 1-1 and Sune Andersson added another goal to ensure Sweden’s lead at half-time. Twenty-three minutes into the second half Jeppson scored his second, a perfect poacher’s goal to seal a famous victory. Although he didn’t score any after his opening game brace, Jeppson played three more games in World Cup, helping his country to finish third.

Jeppson was already an Allsvenskan star and in 1951 he would get his first chance to wow spectators of a foreign league. While studying English in London he went to watch a match between Charlton Athletic and Blackpool hoping to catch a glimpse of Stanley Matthews. Charlton, who were deeply embroiled in relegation battle, approached Jeppson to play for them and he signed up as an amateur, becoming only the second Swedish player to represent an English club. There are several stories as to how Jeppson ended up at the Valley, one of which says that he actually wanted to join Arsenal but iconic Addicks coach Jimmy Seed intercepted him, took him to lunch at Savoy’s before convincing him to join Charlton. Regardless of the origin, what followed was one of the most remarkable cameos ever seen.

Jeppson made his debut against relegation rivals Sheffield, scoring an 89th-minute winner to seal vital points. ‘Hasse Goldenfoot’ had never played club football outside Sweden but he showed little or no regard for the rigours of English football. His debut goal was followed by crucial strikes against Liverpool, Stoke City Chelsea and a brace against Wolverhampton Wanderers – ensuring Charlton’s safety. His most remarkable performance in England and one of the greatest games in Charlton’s history came on 24 February 1951. Jeppson struck a fantastic hat-trick to cement a 5-2 victory over Arsenal, the worst defeat the Gunners had suffered at home since 1928.

With a tally of 9 goals in 11 matches despite being part time, Jeppson left The Valley as a hero, carrying an array of gifts given by supporters and the club – a dinner set, golf clubs and a memento trophy. He played the rest of the season for Djurgardens but would soon make the big leap and follow the path a number of his countrymen had taken already.

After seven rounds of matches Atalanta were in dire straits in the 1951/52 season of Serie A. They were third from bottom and had already suffered the humiliation of a 7-1 drubbing by Juventus. Italy was swarming with Danish and Swedish players at that time, from stars like Gre-No-Li (Gunnar Gren, Gunnar Nordahl and Nils Liedholm at AC Milan), John Hansen (Juventus) and Lennart Skoglund (Internazionale) to lesser known names like Axel Pilmark in Bologna. Jeppson was already famous in Italy thanks to his World Cup exploits and duly accepted a substantial offer of 220,000 Swedish Krona to sign for Atalanta. His decision to turn professional effectively ended his international career, in which he had already scored 9 times in 12 matches.

As he did with Charlton, Jeppson yet again made a strong start for his new club. A debut winner over Como on 28 October 1951 was followed by an 86th-minute winner against Sampdoria, another winner at Fiorentina and an 80th-minute equalizer to rescue a point from Legnano. Jeppson quickly forged a strong partnership with Danish striker Jorgen Leschly Sorensen and, propelled by the duo’s goals, Atalanta rose up the table.

Jeppson continued his strong form throughout the season and regularly found the net against minnows as well as illustrious opponents like AC Milan, Fiorentina, Torino and Lazio. As the season neared its end he launched one last, valiant bid to move his name up the ladder of top scorers, notching four in a 7-1 thrashing of Triestina and three more in a 5-0 win over Torino.

Jeppson ended the season with 22 goals in 27 matches, the fourth-highest total in the league. His was a remarkable record considering he missed the first seven rounds and every other player in the top five list came either from Juventus or the Milan giants. The Swede also finished ahead of stars like Giampiero Boniperti and veteran Silvio Piola. He was ably assisted by Sorensen, who struck ten times and helped La Dea earn a respectable mid-table finish. His performance for Atalanta meant that he was once again poised for a switch, this time to Naples.

Jeppson excelled during his maiden season with AtalantaAs Italy began a miraculous economic recovery following the horrors of World War II, Achille Lauro became one of the most important figures in the peninsula. Lauro had strong fascist connections which led to him becoming Napoli president for the first time in 1936. Post-war he became one of Naples’ premier politicians and an extremely successful businessman thanks to his shipping line Flotta Lauro. ‘The Commander’ was running for the post of Naples’ mayor and, knowing the incredible clout the club had over the city, he decided to bankroll them to challenge for Serie A in 1952 to help his electoral campaign. To strengthen the team right winger Giancarlo Vitali arrived from Fiorentina and, for the left wing, Bruno Pesaola was acquired from Novara.

Both Vitali and Pesaola were seasoned Serie A campaigners and would end up having long, fruitful careers in Napoli, but Lauro still needed to make a star signing. He zeroed in on Jeppson, who had already started to attract suitors. A bidding war with Inter ensued which ended when Napoli coughed up a massive 105 million lire (75 to Atalanta, 30 to the player) for the player’s services. With this transfer, Jeppson’s name entered history books. He was the first player for whom a Serie A club broke the transfer record. He was also the first player in continental Europe to do this – every European transfer record before this had involved British clubs. He was overall only the second non-British player to break the record after Argentine Bernabe Ferreyra’s move from Tigre to River Plate in 1932. No other Swedish player has been subjected to this record since.

Jeppson was besotted with Naples and commented, “When I saw Naples I stood enchanted. She had the smell of the sea that brought me back to childhood, when I was on the rocks of Kungsbacka.” Following his record breaking move he earned a new nickname: ‘O Banco ‘e Napule’ (The Bank of Napoli). Tipped as a title contender, Napoli players and coach Eraldo Monzeglio struggled to cope with the pressure and were slow out of the blocks. Jeppson didn’t have a smooth start as he’d had with previous clubs and couldn’t combine properly with his strike partner, Serie A veteran Amadeo Amadei. He finally got off the mark in October, drawing first blood against Inter at San Siro only to see his team ship five and slump to a crushing defeat.

This pattern stayed unchanged in the next round when Jeppson yet again gave Napoli the lead against Lazio but a second half collapse saw them lose 2-1. The Partenopei’s title push soon lost steam, and dressing room morale dipped as an increasingly irate Lauro demanded better results. The star striker was also not living up to the billing of world’s most expensive player. He scored against heavyweights like Juventus, Roma, Fiorentina, Inter and Lazio, but went missing against smaller teams. Napoli eventually finished fourth, Jeppson was jointly the club top scorer, albeit 14 goals was a small return for his price tag.

Bolstered by the arrival of goalkeeper Ottavio Bugatti, Napoli and Jeppson began 1953/54 with a swagger. Victories over Palermo and Torino were followed by a brilliant 6-3 pounding of Atalanta. Jeppson was ruthless against his old club, plundering four goals. Three weeks later, the Swede scored once in each half as Napoli picked up a 4-0 win over Lazio in Rome. Despite a good start, however, Napoli’s campaign was yet again hamstrung by inconsistency and they eventually finished fifth. For ‘Hasse Goldenfoot’, this season was a personal best as he found the net 20 times, finishing just behind Nordahl in the race for Capocannoniere. One of his season highlights came against bitter rivals Juventus on the last day. Juve took the lead twice only to see Jeppson cancel it each time. Then, with 15 minutes left on the clock John Hansen struck Juve’s decisive third goal.

Jeppson was blessed with most of the attributes that defined a good centre-forward in 1950s. He was strong in the air, physically agile and technically gifted. What he lacked was the tanker-like penetration of Nordahl or neat finishing of Hansen. Indeed, while he sometimes scored brilliant individual goals, Jeppson was also known to miss easy chances. In spite of his failings, he was a popular player among the Napoli faithful thanks to his good looks and natural flair. He was also an accomplished tennis player, once ranked in Swedish top ten, a keen student of economics and a darling of Naples’ social circles. His popularity saw him featured in the movie ‘Brudar och bollar eller Snurren i Neapel’, alongside Skoglund and Gunnar Gren.

As he turned 30 and started his third season in Napoli, it soon became clear that Jeppson was in decline. He missed a major part of the season due to injury as Napoli slid down the table. He fell out with Lauro, who accused the Swede of being lazy, and it was rumoured that an extramarital affair had robbed him of focus. He came back late in the season, helped to put both Roman clubs to the sword, but could do little to prevent his team finishing sixth.

His Napoli contract was nearing its end and Jeppson was in talks with Inter for a switch. Lauro, despite being disenchanted by his record signing, didn’t want to sell him and decided to give the squad a final push by signing Brazilian striker Luis Vinicio. However, any hopes of the duo starting off on the right foot was laid to rest on 10 September 1955. Jeppson, allegedly returning from a meeting with Inter officials, suffered a horrific accident as his Alfa Romeo crashed. His driver was killed and he was injured, delaying his start for 1955/56 season.

An 8-1 victory over Pro Patria, Napoli’s greatest winning margin at home to date, where Jeppson grabbed two and Vinicio a hat-trick, proved to be a false dawn. The strikers never gelled. Jeppson and the club had fallen out of love with each other. Although one of his goals ensured an away win over Juve, ‘Hasse’ could only tally seven goals, his least productive season in Italy. Lauro’s grand plan of Serie A dominance had crashed and burned spectacularly with Napoli finishing 14th. Vinicio was the club’s top scorer and, inevitably, Jeppson was shipped off to Torino.

On the verge of retirement, his numbers in Turin were pretty good: eight goals in 19 matches. Always a scorer on big occasions, Jeppson duly found the net against Milan and Roma. For Granata fans his greatest performance came in the Derby della Mole that season, when he scored twice in an emphatic 4-1 victory. Poetically, his last ever Serie A goal came against Napoli.

Jeppson’s Serie A record of 82 goals in 151 matches was commendable, even if not at the incredible levels of Nordahl or Hansen. His ability to find his scoring boots against the top teams was awesome and somewhat made up for his inconsistency.

Retrospectively it could be argued that he didn’t quite live up to the billing of world’s most expensive footballer. It is also true that his transfer was one of the first instances of the now common phenomenon of a fee being driven up by multiple clubs competing for a footballer. Nonetheless, he remained a popular figure among both Charlton and Napoli fan bases until his death on 22 February 2013.

Jeppson was inducted into the Swedish football Hall of Fame in 2009. A year before, he revisited the San Paolo and watched a match sitting among fans who chanted his name. Perhaps, for a few moments, the greying old man was transported back to the days when he was known as The Bank of Napoli.

Words by Somnath Sengupta: @baggiholic

Thanks to Roberto Baggio, Somnath became an admirer of Italian football and Juventus in 1994. He has contributed to sites like In Bed With Maradona, These Football Times, Back Page Football and The Hard Tackle.

Jeppson did not have an extramarital affair in Napoli, as he only married in 1957 (Emma Di Martino, a daughter of a wealthy magnate). What the article may be referring to is an affair with Italian tennis star Silvana Lazzarino.