No matter how pithy the quote, football should never become a matter of life and death. Nor should it be considered ‘war minus the shooting’, though we are often guilty of treating it in such Orwellian terms. But the truth is, tribalism is an inescapable element of the game and often leads to conflict.

The ugly scenes outside Anfield ahead of Liverpool’s Champions League semi-final against Roma were both tribal and violent. It seems clear now that a group of Roma ultras were the perpetrators. As a result, Liverpool supporter Sean Cox was hospitalised and remains in a critical condition. Unfortunately, this is not the first time Roma – or Italian – ultras have been involved in matters of life and death. Roma president, James Palotta, has strongly condemned the violence, labelling those arrested as “just a couple of fucking morons.”

Undoubtedly such abhorrent behaviour is the preserve of a minority, but unfortunately this minority constitutes more than just a couple of morons. Violence, whether it be motivated by intra-club rivalries, political affiliations or the disaffection of a neglected social class, is part of the dark underbelly of Italian ultra-culture. Writing about such a sensitive subject is never easy, but the purpose here is not to sensationalise or legitimise this culture, but instead contribute to understanding its origins and why it persists.

The origin of the ultras

The etymology of the term ‘ultra’ comes from the Latin word meaning beyond or extreme. Its usage in terms of fanaticism is said to have derived from the 19th century French term ultra-loyaliste, a right-wing political faction who supported the restoration of the Bourbon Monarchy following the fall of Napoleon. Today, football ultras are generally known as groups of hard-core supporters whose behaviours go beyond that which is considered usual.

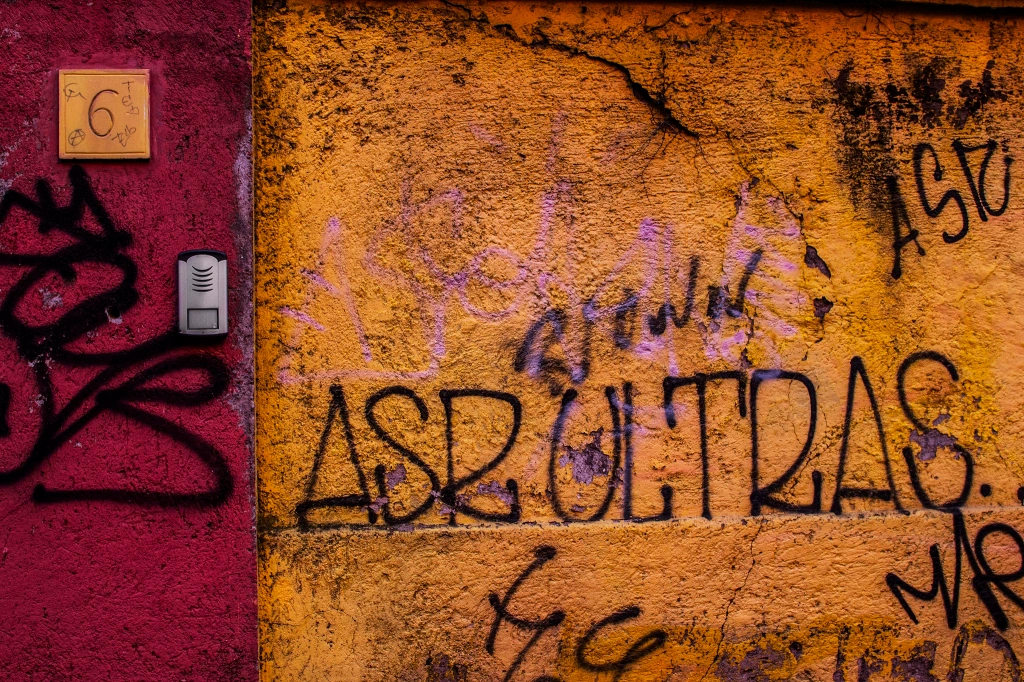

In Italy, these groups have become extremely organised and a powerful element of civil society. Their identities are often underpinned by local and political loyalties and their support for their club is vehement. They are the fans who provide the enchanting match day atmosphere: the mass choreographies, the eclectic mix of banners, flags and flares, and the incessant wall of noise generated from the Curvas (the bends located in the south or north end of Italian stadia).

But this social movement is also a product of its time, especially in Italy where the phenomenon originated in the late 1960s to 70s. It is impossible to detach violence from the political backdrop of an era known as the Anni di Piombo (Years of Lead). This civil conflict polarised Italian society into groups of politically active youths, pitting left-wing and right-wing paramilitary factions against each other. These tensions spilled over into football, leading to the presence of battle-hardened neo-fascists and communists in the stadia.

At AS Roma, for example, two groups of ultras were founded in the early 1970s, one with allegiances to the far-left (Fedayn) and the other to the far-right (Boys Roma). Both mixed politics, violence and football freely. According to reports, one of Sean Cox’s assailants is a member of the Fedayn group, who remain active on the Giallorossi’s Curva Sud. Indeed, it is quite common to find a plethora of different cliques within one fan base, some holding conflicting ideologies and allegiances. This is not to say that every group of ultras is strictly political; the movement just happened to be born in an era when everything contained political significance on the peninsula.

Add to this the already combustible nature of Campanilismo (local patriotism) and civic rivalry in Italy – sentiments underpinned by age-old parochial hostilities – and the picture of where this culture of violence originates becomes clearer. But what of the history of Roma’s ultras in particular?

The ultras of Rome

On April 17, 1944, Nazis conducted the second biggest raid in Rome at the neighbourhood of Quadraro. A zone well known for its anti-fascist sentiment, the Germans rounded up about 700 men and deported them to the concentration camps where most perished.

Fast forward 30 years and the people’s political sympathies were the inspiration behind the founding of one of Roma’s most renowned ultras. Fedayn was formed in the neighbourhood by a man called Roberto Rulli, a well-known communist. Named after a Palestinian liberation group, they maintained the political stance that opposed the Third Reich during World War II and one which ensured the group also became militarised. While their support for Roma united them, their political leanings placed them in direct opposition to Boys Roma, also founded in 1972. The Boys were the opposite end of the political spectrum, espousing neo-fascist militarism based upon nostalgia of Mussolini.

Sociologists Alberto Testa and Gary Armstrong have studied the politics of the ultras movement in Rome and observe that, “from the 1970s … political ideology became more evident among the hardcore AS Roma supporters.” The academics even coined the semantic ‘UltraS’, to distinguish those groups whose ideology lies at the heart of their identity. Violence is also part of this extreme ideology.

Roma: The Alternative Club Guide

Accustomed to violence

In 1977, Commandos Ultrà Curva Sud was founded in an attempt to unite the far-right and leftist groups under one banner. But their efforts were soon tempered by tragedy. In 1979, Lazio supporter, Vincenzo Paparelli, was killed by a rocket fired from the Curva by a Fedayn member. The death of the husband and father of two led to national mourning. But violence had become part of the Italian body politic.

During this time of social turmoil, Italian citizens witnessed violence on an almost daily basis, and acts of political terrorism were committed by both sides. A year before Paparelli’s death, the communist Red Brigades kidnapped and assassinated the former Italian Prime Minister, Aldo Moro. A year later, in 1980, 85 people were killed in the bombing of the Central Train station at Bologna, an attack allegedly perpetrated by the neo-fascist organisation Nuclei Armati Rivoluzionari. The Italian state no longer held a monopoly over violence and lost its legitimacy, causing both a crisis in confidence among the Italian populace and an upturn in the use of brutality on the streets. Italian football became part of this volatile atmosphere.

In Italian stadia, Paparelli’s death was a tipping point which led to further extremism. On June 4, 1989, teenager and Roma fan Antonio De Falchi fell unconscious and died of a heart attack after being chased by 10 Milan ultras from Milano Centrale station. You can still find his memorial flag hoisted in the Roma’s Curva Sud today.

Just a year later, the Tangentopoli scandal of the early 1990s exposed mass political corruption with more than 400 city and town councils becoming dissolved. This led to further distrust of the political establishment, creating a disillusioned social class who were in desperate search of an identity and outlet for their frustrations. The terraces of the stadia and the socio-political clout of the ultras offered one such outlet. As a response to a failed government, paramilitary political groups once again arose, which resulted in numerous clashes between ultras and the authorities.

Hostile Anglo-Roman relations

Following a UEFA Cup match between Roma and Middlesbrough in 2006, fans trickled down to the Drunken Ship, a local but international pub. Knives were drawn, and several people were stabbed. In Rome, this knife culture is known as ‘Puncicate’, a tradition dating back to Medieval Rome. Its aim is to humiliate an enemy by drawing blood with a slash to the buttocks. The incident saw Rome dubbed ‘Stab City‘.

Six years later, Tottenham fans – known for their large Jewish following – were attacked by Lazio ultras at the same pub. However, two of the assailants were Roma ultras, and not Lazio – Tottenham’s opponents on that day. In a rare turn of events, the hooligans from Italy’s fiercest rivalry had banded together in the name of their neo-fascist ideology.

Before the 2014 Coppa d’Italia final in Rome, a clash broke-out between Daniele De Santis, a former leader of the Roma ultras, and rival Napoli fans. Ludicrously, the match didn’t even involve the Giallorossi, but the presence of their fierce rivals in the city led to violence. De Santis shot three Napoletani, including Ciro Esposito, who died of his injuries two months later. A neo-fascist well-known to the authorities, De Santis had also played a part in the infamous Derby della Capitale of 2004, in which ultras from both sides interrupted the game (causing it to be abandoned) after false rumours that the police had killed a child.

When framed in this context, it is clear why the recent events at Anfield seem less like an isolated incident and more like another chapter in a long and dark tale. A fact further emphasized when considering the provenance behind that clash. In 1984, Liverpool beat Roma on their own soil to claim the European Cup. At the time, English fans were regarded as the most formidable (a theory that still lingers in Italy today), and once beaten on the pitch, Roman pride could only be restored by driving these ‘barbarians’ (an epithet given to Liverpool fans by a popular Italian magazine before the final) from their territory through violent intimidation. In subsequent meetings with English teams, including Liverpool, Manchester United, Arsenal and Chelsea, the challenge of maintaining that reputation has often fuelled events.

Needless to say, the more menacing elements of Italy’s ultras are no strangers to violence. As an Udinese supporter once told The Gentleman Ultra in an exclusive interview:

“With regards to violence, it is one of the aspects that set the ultras apart from normal fans. It is difficult for people to understand but, for us, being an ultra means being prepared for physical confrontation with opposition ultras.”

But despite the deep-seated nature of these tendencies, the number who act in a violent way remains relatively small. For most ultras, the priority is to support their team in the most positive way, and the theatre they create contributes massively to the overall spectacle of calcio. However, the challenge of eliminating the lingering violent element without dampening that raw passion is one that remains to be overcome by the Italian state.

Words by Luca Hodges-Ramon: @LH_Ramon25, Wayne Girard: @WayneinRome & Neil Morris: @nmorris01

The Gentleman Ultra would like to take this chance to say our thoughts are with Sean Cox and his family at this most trying of times. Forza Sean!