On 12 December 1969, an explosion ripped through the foyer of the Banca Nazionale dell’Agricoltura in Piazza Fontana in Milan. Seventeen people were killed and 88 more were injured. In Rome, a simultaneous attack injured 14. Another unexploded bomb was later discovered at Milan’s La Scala opera house.

In Italy, as across the globe, this was a time of deep social unrest and political uncertainty. The Milan bombing marked only the beginning of a series of attacks that would become known as La strategia della tensione, a tactic of committing bombings and attributing them to others. Right-wing terrorists hoped to convince the Italian people that the bombings were the work of a communist insurgency and, in so doing, sabotage the left’s chances of forming a government. Italy, not for the first time, was at war with itself.

Over the next two decades, 428 people were killed and over 2,000 injured. The worst atrocity came on 2 August 1980, when a devastating bomb ripped through the central train station in Bologna. Eighty-five people were killed and more than 200 wounded. The legal and political fallout from Italy’s years of terror would rumble on well into the next century, with the role of the government and the security services being a particularly bitter source of contention. Conspiracy theories abound and controversy continues to this day, standing in the way of any meaningful attempt at truth, reconciliation and closure.

In Britain, comparable historical events are somewhat euphemistically remembered as ‘The Troubles’. In Italy, these years of terror are more dramatically known as the ‘Anni di Piombo’ (the ‘Years of Lead’), a reference to the appalling number of bullets fired – for as well as indiscriminate mass bombings, assassinations were commonplace. These brutal slayings culminated in the kidnap and cold-blooded assassination of former Prime Minister Aldo Moro, a murder which shook the already reeling nation to its core.

Against this backdrop of bloodshed, ideology and violence, football was a rare unifying force, bringing communities together, if only for 90 minutes. In an era before it became big business, the stadium was a place where, for a short time on a Sunday afternoon, political division and hatred could, in a certain sense, dissipate. It was an era when players stayed out late before games, drank, smoked and generally lived the high life. On the pitch, they didn’t bother with shin guards, they wore their socks around their ankles and played with a raw freedom that seems unrecognisable by today’s standards. This was a time when the personality of the player mattered more than technical ability. It was, as Italian author and journalist Matteo Fontana’s new books suggests, the era of the wild horse. The antics, both on and off the pitch, of players like Gianfranco Zigoni, Paolo Sollier, Ezio Vendrame and Giorgio Chinaglia, provided a welcome distraction from the turmoil and violence that was taking place off it.

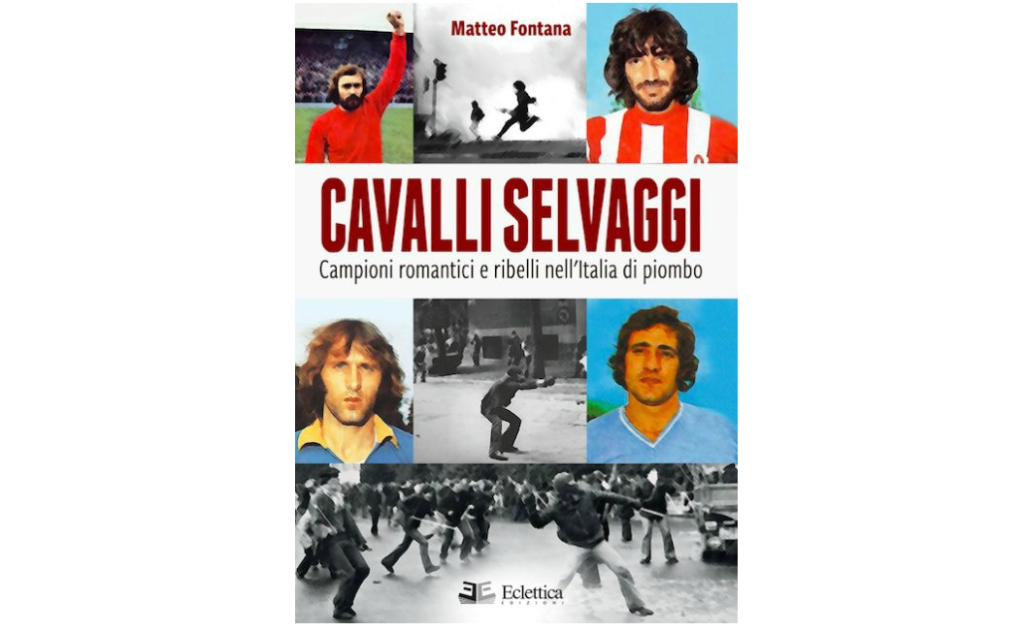

Not long after its publication, I caught up with Matteo in Verona to discuss his new book Cavalli Selvaggi: Campioni romantici e ribelli nell’Italia di piombo.

Richard Hough: Italy’s so-called Anni di Piombo provide the dramatic backdrop to your new book Cavalli Selvaggi. For Italians, what were these ‘years of lead’?

Matteo Fontana: In the 1980s, when the most violent years of terrorism had already passed, Sergio Zavoli, one of Italy’s greatest broadcasters, presented a programme called ‘La Notte della Republica’. This was a dark time. A terrible period. A period of violence, of bloodshed. In fact, a period of lead, which led to the massacre of a generation in the name of political ideology.

Italy at this time occupied a significant strategic position between east and west. Rosario Priore, a judge involved in the fight against terrorism, subsequently described Italy in those years as a borderland between the NATO area and the Soviet bloc. Italy was, in fact, a demarcation zone between these two great competing interests. And like all borderland territories, there was tension and conflict

From this dark period, however, there also emerged, I don’t want to say something positive because it was such a dark time, but it was also a period of great cultural fermentation and progress. From such suffering, Italians somehow managed to pick themselves up and find an outlet that went beyond just political ideology, in what was, nonetheless, the traumatic context of this undeclared civil war, a tragedy in which more than 400 people died and which continues to stain the history of this country in a profound and terrible way.

RH: What role did football play, then, during these terrible years of terror?

MF: Football was still remote from the commercial interests that were to follow in the later part of the 1980s and in the 1990s. It lacked the significant financial investment and international dimension with the huge profit margins that were to follow. In those days, it was still ‘our’ football. A football for the people. A tremendous sport. A sport that was a common thread, which had the capacity to mend the torn fabric that was Italy in those dark days. In particular, there were these wild horses, these champions, it’s a crude metaphor, but these outsiders were wild, they didn’t follow the regular rules of the game.

RH: Tell me more about these wild horses. Who were they?

MF: Naturally in Verona, there was the local legend, Gianfranco Zigoni [who played as a forward for Hellas in the 70s]. Again, he was an outsider. He had a certain idiosyncratic approach to discipline, but at the same time with a simple spark of genius he had the extraordinary capacity to win a football match by himself. Zigoni was idolised in Verona. The children would carve his name on the church pews during Sunday mass. He was emblematic of a style of football played in those days. When a teammate’s goal was disallowed for offside, Zigo confronted the linesman and suggested that he stick his flag up his arse!

These guys were crazy. Great footballers. Huge personalities. If they weren’t great footballers, they would have been great artists, actors or performers. They were great footballers who could, if they had behaved differently, have been even greater. But then they couldn’t do anything other than be themselves!

RH: Is there still room in modern football for such rebels? Do they exist?

MF: No. It would be very difficult because in modern day football, with social media, the smallest gesture can become a major scandal. Giorgio Chinaglia, another great character from that era was a great leader and striker for Lazio, helping them to win their first scudetto in 1974. He was a controversial character, a fierce competitor. During a derby with Roma – and remember this was during a highly volatile period when there were few safety checks in place inside the stadium – Chinaglia scored a penalty and then ran to celebrate in front of Roma’s Curva Sud. His inflammatory gesture, pointing towards the Roma fans, can only really be described as arrogant. Today it would cause an outcry, perhaps even a parliamentary inquiry!

Of course, there was television in those days, but not the same 24-hour demand for sports news that exists today. Yes, there are characters like Balotelli or Cassano, but they are exceptions. Today footballers have to behave. They have to be disciplined. They need to fit in, to follow the rules.

RH: Finally, are there any plans to publish your books in English?

MF: Well, it would be necessary to find a local publisher, a translator and then, of course, there is the question of the market. If my books would be of interest to readers in England, Wales and Scotland, then that of course would be a source of great pride, not just for Eclettica who published them, but also for me as a writer, because the possibility of extending the depth of knowledge and understanding of these important events would be a privilege for me.

More like this: The miracle worker: Author Matteo Fontana talks Osvaldo Bagnoli and Verona

Like many fans of Italian football, my love of the Italian game extends only as far back as the iconic World Cup of 1990 and James Richardson’s unmissable Gazzetta Football Italia of the same era. Before reading Matteo’s book, the heroes of the preceding generation, and indeed the wider geopolitical situation in Italy at that time, were largely unknown to me.

I knew little of Zigoni, a quintessential striker of the 1970s. Genius and flawed in equal measure. Intolerant of rules and orders, capable of bringing a pistol to a contract negotiation and then continuing as if nothing had happened! Then there was Torino’s Gigi Meroni, the Italian George Best. In a conservative society, he was a genuine free spirit, an artist both on and off the pitch. He designed his own clothes. He painted, wrote poetry. His life was tragically cut short when, aged just 24 he was hit by a car. The driver of the car that killed him happened to be a young Torino fan named Attilio Romero. Meroni was his idol. In a bizarre twist of fate, Romero went on to become the president of Torino. Fifty years after his death, fans at the Stadio di Olimpico in Torino still regularly chant his name.

Cavalli Selvaggi revisits those halcyon days when shorts were short, hair was long and football existed in a simpler, purer form. But Fontana reminds us that it impossible to separate football from the wider social context in which it is played. In 1982, the Azzuri lifted Gazzaniga’s gleaming new world cup trophy which was soon followed by the arrival of the first great wave of international superstars to Italian football. This coincided with a marked decline in domestic terrorism. Italian football, like Italy itself, seemed to be entering a new era. The day of the wild horse was over.

Words by Rick Hough.

Grazie to Matteo Fontana for his time and insight.

You can order a copy of Matteo’s book HERE.