“The next young player who says he does not want to play for England should be ordered to ring the parents of a soldier who has died serving his country in Afghanistan and tell them his reasons.“

The above is a quote from a 2014 tabloid newspaper column written by former England striker Ian Wright about the apparent unwillingness of certain England players to turn out for their country. The absurdity of this suggestion hardly needs to be spelled out. For example, what, in Wright’s world, is a bereaved parent supposed to make of a call from an England player to give his reasons for skipping a friendly against Belarus? Are they supposed to find this comforting or is it designed to upset them? If you find yourself asking these sorts of questions, I suspect you have already given the idea a great deal more careful thought than Wright did at the time, so the joke’s on you.

Wright’s comment however, is not an isolated incident, merely a particularly hamfisted example of on odd tendency to conflate football with the military. From England fans’ habit of singing songs about World War II to the seemingly never-ending poppy controversies, there seems to be an idea that because a football team represents a country it is, in some sense, a division of the armed forces.

This is reflected in the old social media cry that soldiers should be paid footballers’ wages. The choice of these two professions rather than, say, nurses and cricketers or policemen and rugby players is far from coincidental. Partly it reflects the fact that both professions consist largely or young working class men, but it also reflects the fact that both are pillars of English exceptionalism, that’s why the chant is “Two World Wars and One World Cup.”

At the same time, soldiers and footballers are often painted as opposites: soldiers are disciplined, humble and self-sacrificing while football players are vain, whining primadonnas. The idea seems to be that if the footballers could be a bit more like the soldiers, they might do a lot better. This is itself just a specific strain of the mindset (usually held by people who never served themselves and are now too old to do so) that what the youth of today really need is good spell of national service.

In light of the above, I can scarcely imagine how these people’s hearts will soar, or perhaps turn green with envy, at the sight of these images of Paolo Maldini and Roberto Mancini in military fatigues in 1988, ready to do their national service.

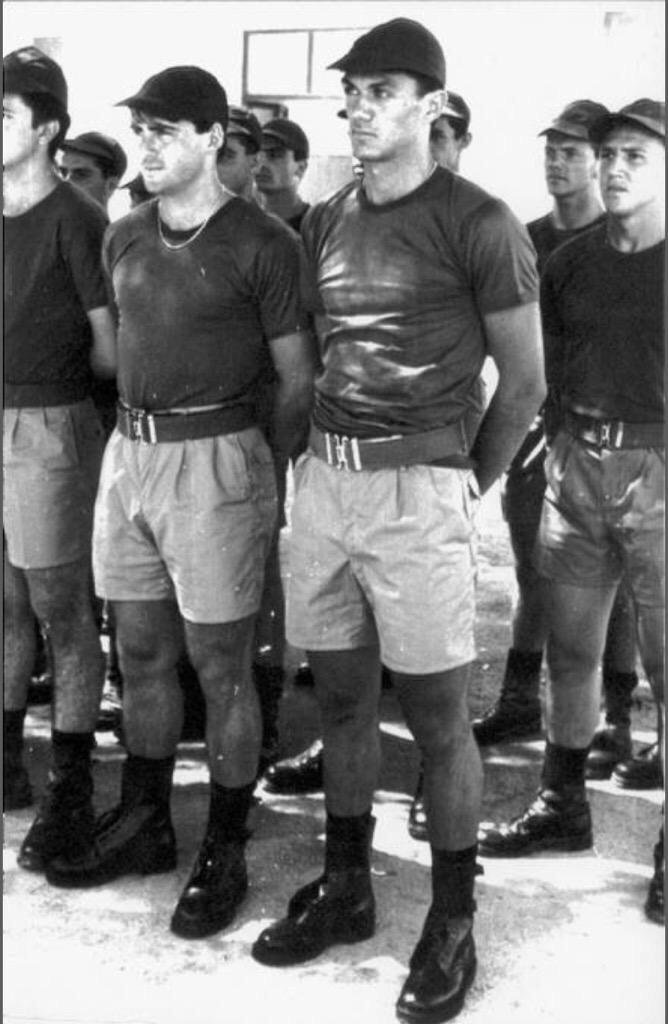

Mancini & Maldini during national service (Source: Calcio Nostalgico via Twitter)

In Italy, compulsory national service remains on the statute books although it was gradually reduced in duration from the 1970s onwards, and was ultimately suspended completely in 2005. This meant that the likes of Maldini and Mancini, by then both regular starters for their Serie A clubs (AC Milan and Bologna respectively) and for their national team, were obliged to serve a 12 month term in Italy’s armed forces.

Given their fame, when Maldini and Mancini reported for duty it was a big event reported by dozens of journalists and followed by football supporters. Roberto Baggio did his national service around the same time while in 1995-1996 Fabio Galante, Marco Delvecchio, Alessandro Del Piero and Fabio Cannavaro all served together, complete with snappy khaki uniforms and full-on ‘jarhead’ haircuts.

However, if this is conjuring up images of Demetrio Albertini digging foxholes and Beppe Signori breaking down and reassembling assault rifles then prepare to be disappointed. The professional footballers called up to do national service did not serve in the military in the conventional sense.

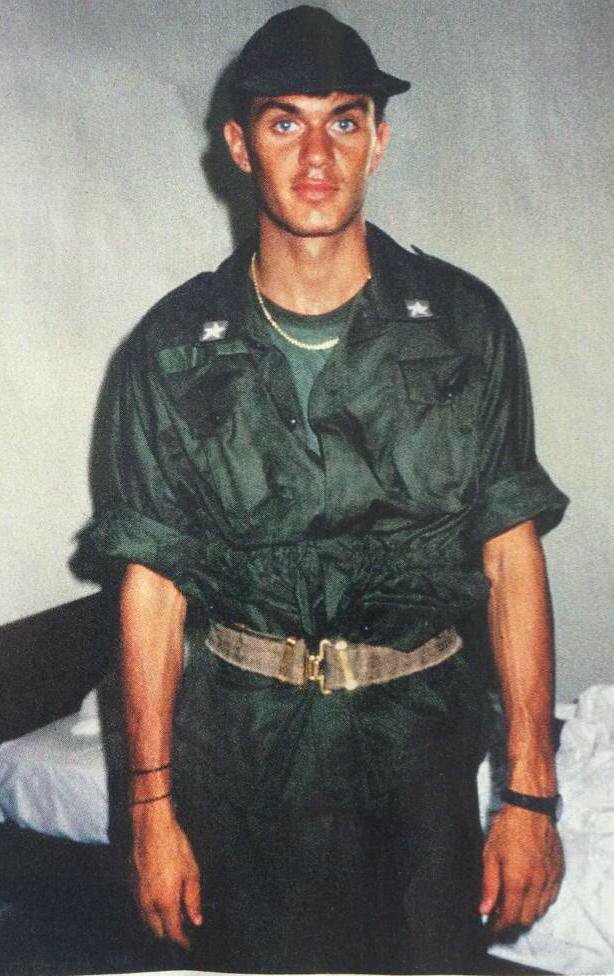

Maldini on duty (Source: Calcio Nostalgico via Twitter)

It was clearly not in the interests of the players or their clubs to risk serious injury (or worse) in conventional military duties, and the military itself would have been well aware of the risk to its public image if promising young footballers were having their careers curtailed by national service. It was far better to snap a few quick pictures of the lads looking great in their uniforms and then keep them out of harm’s way.

Accordingly, after joining up, professional footballers spent relatively little time in barracks and were allowed to fulfil various other commitments for club and country. Del Piero admitted of his time in the Bersaglieri (Sharpshooters): “I only pretended to shoot. In my life I’ve only tried shooting once, with clay pigeons: a disaster. I’ll never be a great hunter like Baggio” (for those who don’t know Roberto Baggio, despite being a buddhist, is famous for unwinding by taking to the woods to shoot wild boar).

Instead, the young players’ main contribution was to play for the Italian National Military Team which competed in the World Military Cup, a football competition for national military teams which started in 1946 and currently takes place every two years.

This was not to say that the players didn’t take their national service seriously, Gennaro Olivieri, then coach of the military team remembered Del Piero in particular fondly:

‘Cannavaro was still at the start of his career but Del Piero had already won a Scudetto at Juve, was an Italy international and had scored in the Champions League but he never did anything to distance himself from the group… We were organising a game in Calabria for a very sick child. Del Piero was in Germany with Juve. I called him. ‘I don’t know if you can make it, but the family of the boy have begged me to tell you they would really appreciate it.’ Ale caught a plane from Germany and joined us. For that I adore him, it’s a memory I will never forget. The Military authorities were proud of the behaviour of Ale and his companions.’

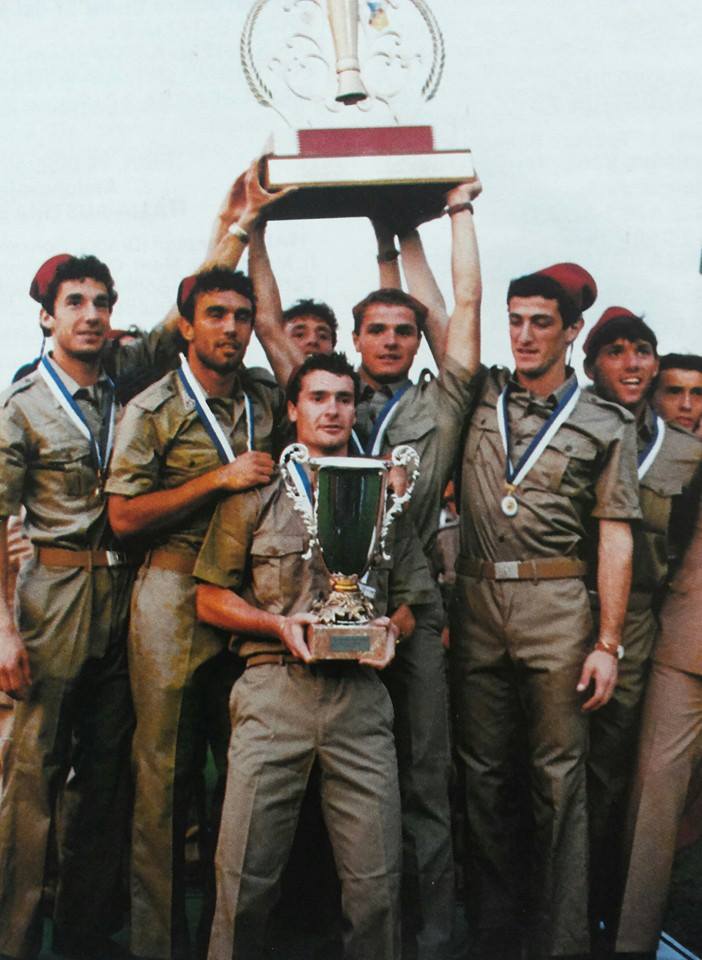

Vialli, Pellegrini, Calattini, Brambati, Ferrara and Baldieri in 1987

Somewhat predictably, thanks to the way its national service worked, Italy is the most successful nation in the history of the World Military Cup, winning eight times, coming second four times and third three times (the next most successful nation is Greece with six, three and three). The team for Italy’s penultimate triumph in Arezzo in 1987 included Gianluca Vialli and Ciro Ferrara: victory can hardly have been a huge surprise.

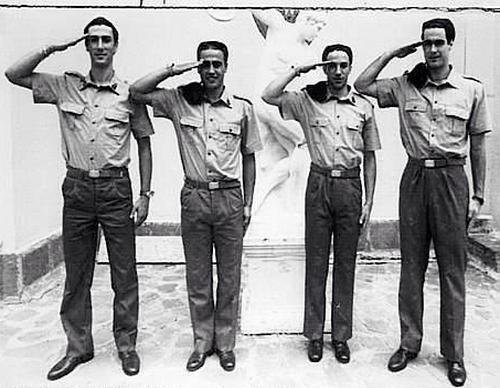

What was surprising, however, was the failure of that quartet of Del Piero, Cannavaro, Galante and Delvecchio, bolstered by Nicola Amoruso, Stefano Fiore e Francesco Flachi, to win the tournament that was held in Rome in 1995.

Italy understandably went into that tournament as heavy favourites and began in impressive fashion beating the Netherlands 3-0, Libya 4-2 and Senegal 8-0. In the quarter-finals they met Cyprus and things seemed to be progressing in a similar manner when they took the lead through Del Piero. However Cyprus hit back twice to take the score to 1-2, where it stayed.

Even more remarkably, Italy finished the match reduced to seven men, following the sendings off of Del Piero, Cannavaro, Delvecchio and Marco Piovanelli. In the tunnel at the end of this game several of the Italian players heavily insulted the referee for his handling of the match resulting in four of them (Amoruso, Flachi, Fiore and Pierini) being suspended from international football for a time by FIFA.

Given the obscurity of the tournament, details of the match are in short supply so it is hard to determine what really went on. However, the dismissal of the notoriously softly spoken Del Piero in particular, a player who was sent off only twice in his long professional career, must surely raise a few eyebrows.

Del Vecchio, Cannavaro, Del Piero and Galante (Source: fabiocannavaroofficial via Instagram)

This result leaves the advocates of national service with something of a conundrum: are we to conclude that military life failed to discipline the overpaid professional footballers resulting in this unedifying display, or worse, did their time in the army simply make the players more aggressive resulting in all those red cards?

On the other hand, Cannavaro and Del Piero did go on to win the World Cup together in 2006 plus they, together with Delvecchio and Fiore, were only two minutes away from triumph at Euro 2000. Perhaps the seeds of that success were sown along with a special esprit de corps in those barracks in Naples in 1995?

Or perhaps, no matter what some people will try to tell you, it’s better for everyone not to try to draw too many parallels between football and the military.