Many among the 70,000 crowd gathered in the San Siro released an involuntary gasp as Spanish referee Antonio Lahoz blew a shrill, long note from his whistle. As the men in azzuro blue slumped to the ground, the scoreboard read Italy 0-0 Sweden. Ever present in football’s biggest stage, Gli Azzurri would not grace the 2018 edition of the World Cup.

Over subsequent weeks, countless words were written to make sense of this disaster. Among numerous causes, the obvious lack of world class talent in La Nazionale was oft mentioned. Indeed, it can be argued that many among the current crop of Italian players are a significant downgrade from the heydays of 1980s, 1990s or 2000s. It is also intriguing to note that Italy’s last failure to qualify for a major tournament actually came during the aforementioned heydays. It came during a time when Serie A was by far the best league in the world and the national squad was filled with world class talents and future Ballon D’Or winners. Despite boasting a star-studded squad, however, Italy failed to qualify for Euro 92, which ended the reign of one of their oft forgotten coaches – Azeglio Vicini.

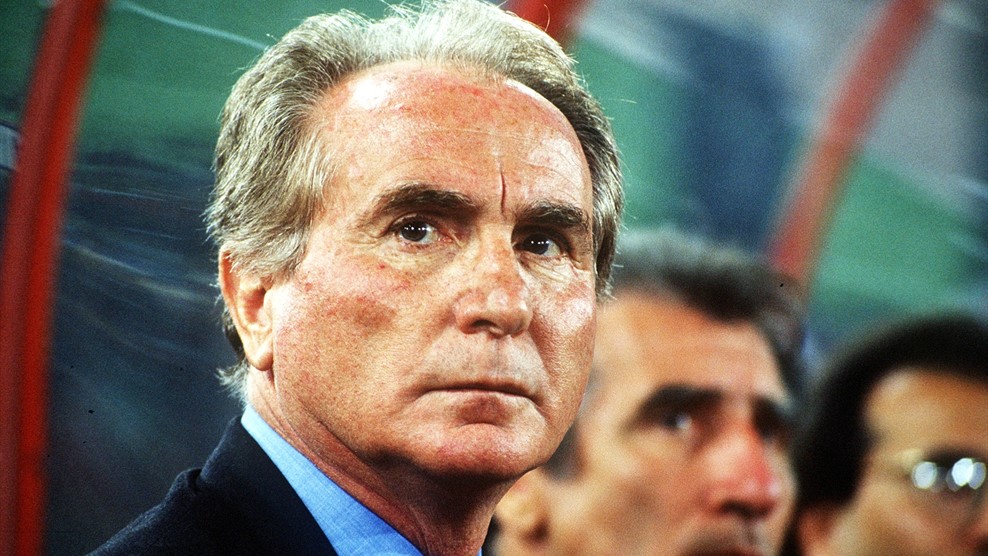

As a footballer, Vicini had a modest career, playing for Vicenza, Sampdoria and Brescia. By late 1960s, he had his first coaching stint at Brescia. A few years later, the young coach was snapped up by FIGC as Italy U23 coach. Vicini was about to begin a journey which saw him work his way up the rungs of youth teams, before finally taking over the senior team. A path followed by Feruccio Valcareggi, Italy’s 1968 European Championship winning coach and much loved Enzo Bearzot, architect of the 1982 World Cup triumph.

Under Vicini, Italy U21 reached the quarter-finals of three consecutive Euros before making the last four in the 1984 edition. When Bearzot stepped down from the senior team after the 1986 World Cup, the time was ripe for Azeglio Vicini to take the hot seat. Gli Azzuri were about to enter a transition period and needing younger blood to begin the rebuilding, they employed a man who had deep knowledge of the youth sector.

The Vicini era began on 8th October, 1986, with a 2-0 victory over Greece thanks a brace by Giuseppe Bergomi. Over next two years, Italy’s new mister would sing to the script, handing out senior national team debuts to prodigal youngsters like Ciro Ferrara, Paolo Maldini, Roberto Baggio, Giuseppe Giannini, Ricardo Ferri and Roberto Donadoni.

The first big test for this new look Italian team came in Euro 88. With Alessandro Altobelli scoring six goals, Italy sailed through qualifiers. However, the expectation from the team was muted given its inexperience and the fact that they were grouped with West Germany, Spain and Denmark, three teams who had excelled in 1986 World Cup. The Italian squad was filled with players in their early 20s and had just two members who were over 30. They negotiated their group more comfortably than anticipated, with victories over Spain and Denmark and a tie with the Germans.

Going into semifinal, Italy were quietly confident. They had played their opponents USSR a few months before and thrashed them 4-1. If Vicini’s team expected a similar outcome, they were in for a rude shock. Soviet coach Valeriy Lobanovskyi was a tactical maverick. He had studied that loss and since then, modelled his team to counter Italian tactics. On a wet night in Stuttgart’s Neckarstadion, the Italians had no answer to Russian mobility and technical proficiency and slumped to a 2-0 loss. Despite an anti-climactic end, Vicini had achieved his objective. He had bled his young team in a major competition and now turned his sights towards the prize that mattered – Italia 90.

The hosts started the tournament as one of favorites and possessing perhaps the squad with the greatest depth in quality. They were initially rusty, but soon became one of the best teams in the tournament. Italy’s stalwart defence, along with stopper Walter Zenga was impenetrable, while Salvatore “Toto” Schillaci became a global sensation with his goals and wide-eyed celebration. Vicini had demanded “seven magical nights” from his team and they had delivered five times. Then came the semi final in Naples against Argentina. When Schillaci gave Italy the lead, the final was within sights – a sight that became a mirage when an uncharacteristic mistake from Zenga allowed Argentina to draw level. The stalemate couldn’t be broken and a penalty shootout ensued which would break Italian hearts. The third place was a poor consolation, Vicini’s Italy didn’t lose a game in the entire tournament but left their fans with a bitter taste of underachievement.

Still licking their wounds after World Cup elimination, Italy turned their focus towards Euro 1992 qualifiers. The Azzuri were placed in Group 3, which looked tricky on paper. Cyprus were minnows in the group, while Hungary and Norway were both extremely capable of pulling off upsets. However, from the outset it was clear that fight for qualification was between Italy and their nemesis from Euro 88 – The USSR.

Vicini’s team could not afford a slow start to their qualification campaign but that is precisely what they did on 17th October, 1990. Playing under bleak conditions in Budapest’s Nepstadion, the Azzurri soon found themselves a goal behind against Hungary when László Disztl rose above the Italian defence and glanced a header past Zenga. It could easily have been 2-0 when an uncharacteristic error from Baresi allowed a dangerous two on three counter attack, but Zenga made a sharp save to deny Kálmán Kovács. Italy got their equalizer in second-half when Fernando de Napoli was bundled inside the Hungarian box and Roberto Baggio converted the resulting penalty. Vicini would also be grateful to Zenga for a superb late save which ensured Italy hanged on to a point.

Celebrating the Italian art of goalkeeping, from Zenga to Buffon

The Soviets had won their first match so Italy knew that they needed to exact revenge for their Euro 88 loss when they met the Eastern Europeans. Vicini fielded an attacking lineup in a 4-3-3 formation – Schillaci was the fulcrum upfront with Mancini and Roberto Baggio on either side.

Sadly, the stacked attack never found synergy on the field. Both Mancini and Baggio often moved into the same channel, leaving Schillaci isolated. With their striking instincts, the duo drifted inwards into Soviet penalty box which meant Italy lacked offensive width. The Soviets, playing a 4-4-2 formation, took advantage of this and used their wingers to peg back any marauding runs from Italian full-backs Maldini and Ricardo Ferri. Italy’s three man midfield also struggled to deal with the numerical superiority of its counterpart.

In the end, it turned out to be a drab encounter with both sides cancelling each other out. Most Italian moves were disjointed and didn’t trouble the Soviet goal. The Soviets were not much better either and on the balance of play, the eventual goal-less draw was a perfect result.

Italy desperately needed to get back to winning ways for which minnows Cyprus provided the perfect opportunity. This time, Gli Azzuri didn’t disappoint. Pietro Vierchowod scored his first international goal to put Italy ahead while Aldo Serena struck a brace and Attilio Lombardo added another goal to complete a 4-0 rout. The Soviets won in Budapest so Italy knew they couldn’t afford another slip.

Confident after their result against Cyprus, Vicini’s team delivered yet another commanding performance against Hungary in Salerno, thanks to two spectacular first-half goals from Donadoni. The Soviets responded with a sound thrashing of Cyprus, putting pressure on Italy who were scheduled to play Norway a week later.

In Oslo, Azeglio Vicini deployed his team in a 4-4-2 formation with Lombardo and Stefano Eranio operating as wingers. Sampdoria’s famous “Goal Twins” Vialli and Mancini were given the job to unlock a Norwegian defence which had kept three consecutive clean sheets. Norway’s tactics were simple – they crowded central midfield and defence, relying on long balls to release their attackers behind high Italian back line. Within seconds of kick-off, Italian players were subjected to clattering tackles as the Scandinavians tried to physically intimidate their opponents.

And these rough and tumble tactics rattled Italy. It took Norway just six minutes to race into a lead as a misdirected header from Lombardo allowed Tore Andre Dahlum to stab the ball in at the far post from a corner kick. Twenty minutes later things got worse for Vicini’s team. A lazy error in midfield saw Lars Bohinen sprint past the Italian defence, feint across a sliding Baresi before beating Zenga with a low shot.

Yet again, Vicini’s tactics seemed to fail on the big stage. While Lombardo huffed and puffed, Eranio was subdued, which led to Mancini dropping deeper to get the ball, leaving Vialli to deal with Norwegian defenders on his own. Italy’s high back line also looked extremely susceptible to the speed of Jahn Jakobsen. As creative outlets lessened, Italy increasingly began to depend on long balls, which were easily dealt with by the towering Norwegian defence. Schillaci came on as a sub and pulled back one goal, but throughout the game Italy always looked more likely to concede than score.

The loss in Oslo had put an almost decisive dent in the Azzurri’s qualification bid. Guerin Sportivo termed this match as “the fjords of evil”. After the Norway result, FIGC head Antonio Matarrese stated, “When we have the mathematical certainty of European elimination, we will entrust the leadership of the National team to a man with proven national and international club experience.” The doomsday clock of the Vicini era was nearing crisis hour.

Vicini’s Italy side lining up for a Euro qualification game in 1991

The USSR were expected to win their home match against Hungary, but Feyenoord star Josef Kiprich became an unlikely saviour for Italy. He put Hungary ahead in Moscow and scored another 84th minute goal to earn an unlikely 2-2 draw. Vicini and his team still had a chance, but they needed to defeat USSR in Moscow.

On 12th October, 1991, Italy and Vicini got ready for a final throw of the dice. The Italian coach had learnt from their previous encounter and started his team in a 5-3-2 formation to prevent being overrun on wings. He also gave a start to Torino’s explosive young talent Gianluigi Lentini. Both teams had their chances – Zenga denied Andrei Chernyshov from point blank range while Ruggiero Rizzitelli struck the post. To their credit, Italy did dominate this match but failed to get a much needed winning goal. The match finished in yet another stalemate. Italy were out of Euro 92, Vicini’s time was up. Six days later, Arrigo Sacchi would become the new Italy coach.

In hindsight, it could be argued Italy’s qualification campaign was doomed from start. Perhaps both the Federation and players were looking for a coach with a more glittering track record, which would suit the star-studded squad. Vicini was an amiable man, but he was also soft and malleable. Throughout his reign, there were allegations that he wilted under pressure of Juventus, Internazionale and AC Milan and gave more preference to players from these clubs. This was a great cause of dismay for Roberto Mancini, Gianluca Vialli, Pietro Vierchowod, Attilio Lombardo and Gianluca Pagliuca – players who formed the backbone of Sampdoria’s greatest team in late 80s and early 90s. Throughout Italy’s campaign negative body language and lack of motivation were all too evident. Even the likes of Franco Baresi made silly mistakes.

Vicini’s tactical approach for big matches was always under question. He was outsmarted in Euro 88 and in the 1990 World Cup semi-final, it was believed that Italy could have closed out the game had Vicini brought on Vierchowod – Maradona’s kryptonite. During the Euro 92 qualifiers, he used three different formations – 4-3-3, 4-4-2 and 5-3-2. More staggeringly, Italy’s forward line was different in every single match! This was sign of a coach desperately struggling to fit players to his system.

It would later come to light that Silvio Berlusconi was looking to oust Sacchi from AC Milan and had contacted FIGC head Antonio Mataresse about the availability of the “Prophet of Fusignano”. Mataresse had wanted to sack Vicini after the World Cup but couldn’t find a suitable replacement at that time. Italy’s Euro 92 qualification campaign was a loveless marriage inevitably hurtling towards an ugly divorce. Even qualifying for the Euros perhaps wouldn’t have saved Vicini’s job.

Despite taking over Italy with a lot of fanfare, it Sacchi didn’t do much better than his predecessor. Though he led Italy to the 1994 World Cup final, his side then bowed out in the Euro 96 group stages.

Vicini’s era was vital in rebuilding La Nazionale. It triggers a wave of nostalgia among Calcio fans. But it was also an era which promised plenty, but delivered less than it should have. And though the recent tenure of Italy coach Giampiero Ventura was undoubtedly more disastrous than Vicini’s, unfortunately for both, their time in charge of the Azzurri ended in the same unthinkable manner: with Italy absent from a major tournament.

Words by Somnath Sengupta: @baggiholic

One Comment