Origins

If the word ‘staffetta’ is translated into English, it roughly means relay. The word is generally associated with athletics – contests between two or more teams in running or swimming – that consist of competitors getting ‘tagged’ in within the course of a race. In Italian football parlance, the word carries negative connotations. It speaks of reluctance from a coach to trust two equally brilliant players to play at the same time, and rather to play one at any given time. With the player that was benched generally coming on to replace his ‘rival’.

Italy has a complex history with the issue of staffetta, the most famous of which took place at the 1970 World Cup in Mexico. Azzurri coach Ferruccio Valcareggi was blessed, or perhaps cursed, with having Gianni Rivera and Sandro Mazzola – both star players for Milan and Inter – in the prime of their careers.

Valcareggi believed with a system that deployed two out and out ‘bombers’ in Gigi Riva and Roberto Boninsegna, he couldn’t also field both Mazzola and Rivera together. This, he felt, would hugely imbalance Italy’s system and leave them defensively vulnerable, something that’s considered sacrilege in Italian football. Both Mazzola and Rivera were hardly known for their defensive legwork.

So it was Valcareggi who came up with the ‘relay’ system, with Rivera and Mazzola playing a half each as a way of compromise. While the system worked to an extent, the move was widely criticised, with many imploring Valcareggi to devise a way to play both. Not only was the country divided into ‘Mazzoliani’ and ‘Riveriani’, but indeed large swathes of the dressing room were too, with it being reported that defenders and midfielders favoured Mazzola, due to his superior work rate, and Riva and Boninsegna clamoring for Rivera due to his ability to create.

In the end, Rivera and Mazzola played a paltry 6 minutes together, in the dying minutes of the World Cup final with Italy already soundly beaten by the sultry Brazilians. As was custom in that era, thousands of fans flocked to Fiumincino airport in Rome to greet the squad upon arrival. However, it wasn’t an England-coming-home-after-Italia ’90-esque celebration of a great tournament. Italy was greeted off the plane with flying stones, and Valcareggi was forced to flee under the arm of police protection.

The staffetta concept lay dormant, like mount Vesuvius, never to be uttered again, or so many hoped. But fast forward some 28 years later to France ’98, and Roberto Baggio and Alex Del Piero found themselves the latest casualties of the staffetta. The Italian press pitted fallen idol Baggio against current media darling Del Piero.

In the middle stood coach Cesare Maldini, father of Paolo, who ultimately didn’t know whether to stick or twist throughout the tournament. Torn between keeping faith in the out-of-form but preferred choice of Del Piero, or begrudgingly playing the in-form people’s champion Baggio. The Baggio/Del Piero debate became the focal point of talk not just around the country, but also for many who were taking part at the tournament. Players, past and present, weighed in on a theme that played a divisive role in Italy’s bid to win a fourth World Cup.

The issue went right to the heart of Italian football’s ideology. It evoked old fears and anxieties between playing to win and playing not to lose. It exposed Maldini’s inability to harness the huge depth of talent he had at his disposal. In the end, it would leave a bitter taste, regret at what might’ve been.

The Road to France ‘98

In the summer of 1997, Baggio epitomised that of the fallen idol, a player haunted by the weight of his history. Tormented by that penalty miss in Pasadena, his status as one of the world’s best had nose-dived in the ensuing 3 years due to a combination of injuries and ill-advised moves. So much so that by the age of 30, the 1993 Ballon d’Or winner found himself ludicrously unloved and unwanted by the Serie A elite.

Despite having a year left on his contract with Milan, a returning Fabio Capello told him – with the cold ruthlessness that he’s infamous for – there was no future for him at San Siro. The same Capello that had pushed Silvio Berlusconi to sign him only two years prior.

With France ’98 less than a year away, Baggio was driven by a visceral desire, or rather an intense need, to right the wrong of USA ’94. Baggio needed redemption, and most importantly, needed football. It spoke to the sheer volume of talent that Italy had at the time that a player of Baggio’s genius was wilfully ignored for three years. Since the World Cup final, he’d only played a further three times, averaging one performance a year. Arrigo Sacchi, somewhat gleefully, refused to bring him to Euro ’96.

A move to Parma was all but complete until Carlo Ancelotti vetoed the deal. Ancelotti, then a devoted disciple of the Sacchian model, was so deeply wedded to 4-4-2 that he was unwilling to accommodate and threatened to resign if Baggio was thrust upon him. Several Parma players – as the story goes – also made it clear to Ancelotti that Baggio’s presence at the club wasn’t welcome. Enrico Chiesa, chief among them, asserted that if Baggio arrived, he would “go to Barcelona”.

Ancelotti would later regret turning Baggio away, saying in his 2011 autobiography, “How can you give up on someone like Baggio? I was young and lacked the courage to go into something I knew little about (changing systems).”

Incredible to think of it now, but with the Parma deal dead in the water, Baggio had only three options: Udinese, Bologna and a lucrative offer from Japan, where Baggio was, and remains, hugely popular due to his Buddhist beliefs. Baggio knew the Japanese offer wasn’t a viable alternative if he wanted to make Italy’s World Cup squad. Udinese’s offer wasn’t felt to be genuine, and so Baggio joined unfashionable Bologna.

In contrast to Baggio’s trials and tribulations, Del Piero emerged from Baggio understudy to one of the world’s finest players. A domestic double winner by the age of 20, Champions League winner at 21, Intercontinental Cup champion by 22. Their careers resembled two ships passing in opposite directions. Baggio was now seemingly yesterday’s man, evidenced by the fact that by 1996, he wasn’t even shortlisted for the Ballon d’Or, nor would he be in 1997. Del Piero finished fourth in 1995 and ’96.

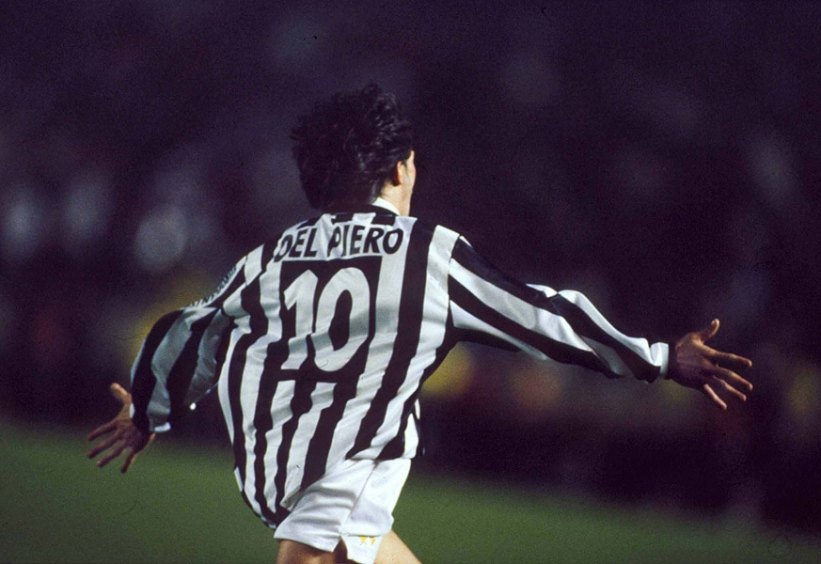

Goal O’ The Times: Alessandro Del Piero vs. Lazio (1994)

Del Piero’s career was on a skyward trajectory, and the 1997-98 season proved the zenith of that three year, most purple of purple patches; 32 goals were rattled in across all competitions, including 10 in the Champions League, the first time double figures had been reached since its 1992 rebranding (and the only time it was achieved in the 24 team iteration).

Del Piero and Ronaldo battled it out in a fascinating footballing arms race; the world’s two greatest players outdoing each other on a weekly basis; almost single handedly propelling Juve and Inter towards domestic and European supremacy.

In terms of cold, hard statistics, 1997-98 would also be Baggio’s career best. Once more the focal point of a team in a very decent Bologna outfit. Baggio, sans famous ponytail, would net 22 times, including goals against old clubs Juve and Milan. Only Ronaldo and Oliver Bierhoff scored more.

The pressure on Cesare Maldini to select Baggio for France ’98 mounted with every passing goal. Maldini, who was appointed Italy coach in December ’96 in the last of what was a semi-traditional route of serving time with the U21s before making the jump to the first team (Enzo Bearzot and Azeglio Vicini also count as alumni).

Maldini, who had given Baggio a recall in an April 1997 qualifier against Poland – his first game in blue for 18 months, ruled Baggio out. Asked in a January 1998 interview about calling up experienced men like Beppe Bergomi, Roberto Mancini and Baggio, Maldini retorted, “I admire and respect them, but the Italian team’s projects and plans does not involve them.”

However by May, the groundswell of support for Baggio’s inclusion was so overwhelming (in a poll run by La Repubblica, 90% of readers wanted Baggio in France), and the fact that Baggio’s 22 goals had lifted Bologna into Europe, it was evident Maldini couldn’t feasibly ignore him. In a funny and antiquated anecdote, Baggio found out about his selection for France ’98 via teletext.

With Baggio’s tunnel of perennial darkness now seeping with flashes of light, his former protégé was fast approaching his own. The Champions League final that pitted Del Piero’s Juve against Real Madrid seemed to be a forgone conclusion. Juve were the overwhelming favourites, in their third consecutive final appearance against a side who hadn’t won the competition for 32 years.

Juve, playing to much of their final history, promptly lost. Del Piero had a poor game, and showed little of the form that saw him rampage through most of the competition en route to the final. To compound the misery, an injury to his right thigh led to speculation that he could miss out on France ‘98. Maldini, and all of Italy, waited with bated breath.

The ecstasy before the agony: Roberto Baggio vs. Bulgaria (1994)

Chile

After several days of waiting, with Gianfranco Zola put on standby, the prognosis came back that Del Piero’s thigh injury was only a strain, and would make the plane for France.

What was immediately clear was that Del Piero’s injury wouldn’t heal before the Group B opener against Chile. With Christian Vieri, fresh from winning the Pichichi award in La Liga with Atletico Madrid, guaranteed a starting place up front in Maldini’s ultra conservative system, the position long earmarked for Del Piero would instead be given to Baggio.

For Baggio, just making it to the tournament was his victory; he’d proved to the doubters that he could still make a difference at 31, that he wasn’t consigned to the history books. Baggio believed he was better than his American incarnate. Not as physically fragile and mentally stronger after four years of struggle. Baggio felt a strong sense of serenity that he’d scarcely known in his career. “I was not just a player, I felt like an older brother of the team, a silent guide, a discreet reference point,” Baggio would say.

After Pasadena, Baggio was ‘vaccinated of any pressure, of any problem, of any eventual defeat’. What could be done to him that hadn’t already before? Went the thinking. Baggio felt bulletproof.

Looking through Italy’s squad for France ’98, in a competition that saw all the heavy-hitters converge on France with high-caliber talent, Maldini’s selection of players stood out. No team could match Italy’s quality either end of the field. A defence of Paolo Maldini, Fabio Cannavaro, Alessandro Nesta, Billy Costcurta and Beppe Bergomi offered wall-like assurance whilst Vieri, Baggio, Del Piero, Pippo Inzaghi and Enrico Chiesa was an attack no other team could rival. Competition was so fierce that Zola, Fabrizio Ravanelli, Pierluigi Casiraghi – who scored the decisive winner in the qualification playoff against Russia – and a young Francesco Totti failed to make the 22. The squad was a nice blend of World Cup veterans and young first timers.

Baggio was under no illusions as to his role at France ’98; to be Del Piero’s understudy. Maldini had purposefully chosen the squad numbers and handed Del Piero the iconic no.10. Baggio took the no.18 that he wore during his days bolted to the Milan bench. “Maldini was always clear with my role in the squad”, Baggio said, “and I respected his decision, I was Del Piero’s sparring partner.”

Italy played a single friendly in the run up to the tournament, a 1 – 0 loss to Sweden, in which nobody shined with the exception of Baggio. It was Maldini’s second, and last, loss over 90 minutes.

Regarding tactics, Maldini was a meat and two veg tactician, there would be nothing spellbinding or adventurous in his style of play. Against Chile, Italy lined up in a classic 4-4-2. The team was:

Pagliuca; Costacurta, Cannavaro, Nesta, Maldini; Di Livio, Albertini, D. Baggio, Di Matteo; Vieri, R. Baggio

Italy vs Chile remains one of the great underappreciated group stage encounters of the modern World Cup era. On a day that more resembled autumn than summer in Bordeaux, Italy struck first when Paolo Maldini launched a long pass down the left channel to Baggio. Baggio, seeing that Vieri had stolen a march on the Chile’s Javier Margas, angled a beautifully weighted pass towards the center of the pitch into his path. Vieri, without breaking stride, slammed the ball home. From back to front in 3 touches. A beautifully crafted goal.

By the 84th minute, Italy were 2-1 down due to two Marcelo Salas strikes, with the second one a particularly marvellous header. Italy, as they tend to do when facing defeat, finally showed a sense of urgency. Baggio dispossessed Francisco Rojas on the periphery of the Chile box and faced with Ronald Fuentes, engineered a brilliant moment of ingenuity by chipping the ball towards his fist. Baggio shouted penalty, and was promptly give one. In truth it was an incredibly harsh decision, there was little Fuentes could do.

Baggio bent over, trying to gather his thoughts, there was only ever going to be one penalty taker. Dino Baggio dragged Chiesa, who had come over to give some words of encouragement, away. The midfielder was a survivor of the traumatic ’94 campaign and knew the ordeal his namesake had went through.

“Of course I thought about Pasadena in those moments,” Baggio later said, he could hardly fail to. It was as if everything and nothing had changed in 4 years. Italy’s last action of USA ’94 involved Baggio in the baking Californian sun placing the ball on circled chalk from 12 yards, and four turbulent years later he stood once again, ready to take a spot kick in Italy’s opening match at France ‘98. Full circle and all that.

Now with the odd speckle of grey hair that glimmered throughout his cropped hair that gave the impression of a more mature, more robust player. Baggio tried to exude calm. He waited for the whistle, and confidently hit the ball hard and low, placing it into the bottom corner of the Chilean goal. It was a remarkable show of strength and composure.

Baggio had saved Italy from a second consecutive opening day defeat. “A small Italy saved by Baggio,” ran the headline from La Repubblica the following day. “Baggio showed great character,” said Maldini, who was so nervous he turned his back as Baggio began his run up.

“I killed the ghost of 1994 with that penalty,” Baggio would write in his 2001 autobiography. It’s hard to believe that he will ever fully rid the pain of Pasadena, yet his redemption in the eyes of the Italian public was complete.

Roberto Baggio’s redemption: A story of two World Cup penalties

Cameroon

It was in the lead up to the Cameroon game that mentions of the ‘staffetta’ emerged. Baggio’s exceptional display against Chile now made matters slightly more complicated for Maldini. Yet Maldini was surprisingly quick to pour scorn over Baggio’s performance. “I’m happy with what Roberto did, but I wait for Alex (Del Piero),” Maldini said to the media. Baggio for his part agreed, saying that he had no problem making way for Del Piero against Cameroon.

Between the clinks and clatters of cups filled with espressos that were set down on bars all across Italy – the country known as the land of 60 million coaches – talk centered around the Baggio/Del Piero conundrum. Should Del Piero play against Cameroon? Should Baggio retain his place after his excellent performance in the Chile game?

The discussion soon made its way from the bars and piazzas of Italy to players past and present. Rivera and Mazzola were asked, given their history, to weigh in with their opinions. Rivera and Mazzola both agreed that Baggio and Del Piero could play in tandem, granted the defence and midfield was reconfigured; Pele, back when not everything he said sounded foolish, also offered insight, arguing that at the 1970 tournament, Brazilians claimed he and Tostao couldn’t play in the same team, and yet they won it together; French legend Just Fontaine remarked that he’d play Baggio, Del Piero and Vieri together; as did Guus Hiddink, at the tournament as Holland manager, who felt playing the trio together could be a ‘winning move’.

It seemed Maldini was at the very least intrigued by the tantalising prospect of a Del Piero/Baggio/Vieri trident. Two days before the Cameroon game, a test match was initiated with the three on one side in a 4-3-3 with Del Piero on the left and Baggio on the right. Many felt Maldini was bluffing, and that he would never inherently break away from his conservative ethos. Others pointed out that in the 0-0 draw with England that sent Italy to the playoffs, Maldini had played Zola as a traditional no.10 behind Vieri and Inzaghi.

Maybe Italy’s inability to score in that bruising game in Rome came into his thoughts, because Maldini kept faith in the Baggio-Vieri partnership for the game against the Africans.

Much was made of Del Piero’s non-enthusiastic response to Baggio’s equaliser against Chile, with the Italian press doing their best to drum up a rivalry. Del Piero had been informed the night before of his exclusion from the starting XI, and on the day of the game tried to put a good PR spin on it, saying, “Playing me from the first minute could be risky, he (Maldini) knows well what Baggio can do.”

Italy ran out winners in what was a fairly routine 3 – 0 win against the overzealous Cameroonians. Baggio laid on an assist for Luigi Di Biagio in the opening quarter hour before Vieri added a further two. Del Piero would finally make his World Cup bow, replacing Baggio with 25 minutes remaining. He almost scored with the most delightful of chips, only to see it brilliant parried over the crossbar by Jacques Songo’o.

Italy needed a win in their final game against Austria to ensure top spot, and to avoid an untimely repeat of the 1994 final against Brazil. With Del Piero now in contention, Maldini was forced to make his first big decision of the tournament.

Austria

The improved performance against Cameroon ended all talk of a 3-pronged attack. On the eve of the game against Austria, Del Piero was at pains to squash rumours of the rivalry between he and Baggio. “It is right that there’s a sporting dualism between me and Roberto, but it’s positive and not negative, which some try to paint,” said Del Piero.

Baggio for his part again reiterated that the starting spot should be Del Piero’s, and felt this will be his tournament and advised him to stay calm. Maldini was glowing in his praise of Baggio, stating that he’d done ‘exceptional things’, yet he was getting increasingly agitated with the incessant staffetta talk, snapping in the pre-game press conference. “It is something from 30 years ago, today it no longer makes sense.”

Del Piero got the nod for his first start in the Stade de France in Paris. Austria still had aspirations of making it into the round of 16, but were undone by a Vieri header – from a Del Piero free kick – and a brilliantly executed give-and-go between Inzaghi and Baggio in the dying moments of the game. Baggio had replaced a tired Del Piero with little less than 20 minutes remaining to a thunderous ovation. It was Baggio’s ninth goal in World Cups – the first Italian to score in 3 tournaments. And as he casually rolled the ball into the Austrian net, few would’ve guessed then that it would be his last for Italy.

Vieri and Del Piero celebrate after Italy’s opening goal against Austria

Norway

Baggio was quite enjoying the role as elder statesman in the squad. The cooker pressure-like environment that had surrounded him for most of his career had all but faded away. France ’98 was earmarked as being Del Piero’s tournament, his coronation, his coming out party. He had featured heavily in Adidas promotional videos and billboards leading into the tournament.

Baggio was all too familiar with the situation; there was almost a sense of déjà vu in France and he sympathised with his struggling teammate. “Del Piero at France ‘98 was me four years later, and I was he four years prior in America,” Baggio would write in his book. Baggio tried to act as a bigger, more experienced brother to Del Piero, and did his best to shield him from criticism.

Baggio publically went to bat for him throughout the tournament, relaying his own story, “he only needs a goal to unlock himself, I was in the same position in America and once the ice broke against Nigeria, everything followed.”

And still, the talk of Maldini starting both together failed to totally dissipate, only ever briefly fading into the background. Brazilian greats Zico and Falcao, both of whom played in Serie A in the mid ‘80s, gave contrasting views. Zico threw his support behind Baggio, feeling that if the 31-year old was fit, he should play, “with 3 touches, he can do anything on the pitch.” Falcao felt the two couldn’t coexist, as it would create an imbalance.

Giovanni Trapattoni, king pragmatist and a man not known for creating swashbuckling sides, believed there was no reason for a relay and they should play together. Trap had managed both for one season in 1993/94 and gave Del Piero his Juve debut in September 1993.

The match against the Norwegians in Marseille was never going to be one for the football purist. Italy had produced rather stodgy performances, only occasionally flickering into life, and this was the Norway of Egil Olsen, long ball advocate.

And so it proved, a dour game was decided by Vieri’s powerful finish early on, his fifth goal of the competition. Del Piero’s ice breaker should’ve come here. He spurned three chances that, many argued, had he been wearing the black and white of Juve, would’ve been taken with relative ease. But Del Piero was succumbing to the pressure.

As was Maldini. Seconds after Del Piero flashed his third big chance past the Norway net, shaving the outside of the post, Maldini could be seen arguing with Italians behind the set of benches in the Velodrome. The issue? Why wasn’t Baggio playing. Maldini had sent him out to warm up early in the second half, and Baggio sprinted, jogged, stretched and jogged some more. It seemed inevitable that he would enter the fray, yet by the time Del Piero was replaced, it was for Chiesa. This incensed a group of Italy fans.

Asked after the game why he ignored Baggio, Maldini bluntly told the RAI reporter that it was ‘none of his business’. Baggio, despite warming up and not playing, thought the episode was quite humorous. “I had to buy a lot of tickets for those fans,” he would jokingly say.

Tensions were beginning to run high.

Del Piero and Baggio pictured during France ’98

France

In the days leading up to the quarter final with France, Maldini became increasingly conflicted; stick with an out-of-form Del Piero or give in to the demands of the public and play Baggio? Del Piero hadn’t performed anything close to the standard he’d set at Juve against Austria or Norway.

By this point Italy was divided into Baggisti and Delpieristi, echoes of 1970. Polls taken around the country showed an overwhelming majority wanted to see Baggio start against France. They believed Del Piero was floundering under the weight of supplanting Baggio.

Hailing from the northeastern corner of the peninsula, Del Piero and Baggio could be heard talking and cracking jokes in Venetian dialect whilst training. Del Piero, maybe not wanting to give anything away with cameras present, give the impression of someone at ease. Baggio again looking the part of an older, wiser brother.

Maldini had switched formations after the Cameroon game, and now settled on a 3-5-2 formation. Maldini, against his better judgement, kept faith in Del Piero to partner the ever-present Vieri against hosts France. Italy lined up as so:

Pagliuca; Costacurta, Bergomi, Cannavaro; Moriero, D. Baggio, Di Biagio, Pessotto, Maldini; Del Piero, Vieri

The quarter finals of France ’98 threw up some remarkable games; Argentina vs Holland became a cult classic; Brazil and Denmark produced a five-goal thriller, and Croatia pummelled a decrepit Germany. Italy vs France didn’t live long in the memory. It was the only goalless game of the last eight. Maldini, petrified over the damage a returning Zinedine Zidane would do, dropped the more refined Demetrio Albertini for Gianluca Pessotto, who was given the unenviable role of man marking Zidane.

The battle of Zidane and Pessotto played out quite like one would assume Zidane v Pessotto would play out. Pessotto, a versatile and hard working player, could do little to tame Zidane, who inched and probed his way around the Stade de France turf with his usual elegance.

Rather depressingly, Maldini instructed Italy to play up to their catenaccio heritage, hoping to hit their opponents on the counter through the speed of Moriero and Del Piero. Having given the initiative to France from the kick off, the hosts dominated and were the only team trying to win the game.

Del Piero, devoid of all confidence by this stage of the tournament, was anonymous throughout and was hauled off in the 67th minute for Baggio, who again entered to loud cheers. Baggio immediately sparked some sense of life into a dire Italy performance, and his in swinging free kick was met by Di Biagio, a carbon copy of the Cameroon game, only this time his header went wide.

Then came the chance, the one that this game is most remembered for by Italians. Albertini, who had come on for the ineffectual Dino Baggio, floated a beautifully lobbed pass to Baggio, who had ghosted in behind Lilian Thuram down the right hand side of the French box. Baggio, judging the situation on pure instinct with little space between he and Fabian Barthez, hit a right-footed volley with the outside of boot that flashed across the net and went narrowly wide. Angelo Di Livio thought he had scored. It would’ve been a golden goal, and changed the course of French history. A matter of centimetres.

Reflecting on the chance in 2010, Baggio believed the execution of the volley was too Baggio-like, too clean, too crisp. “My only mistake was to hit the ball too well, had I hit it a little dirtier I’m convinced it would’ve went in.” Baggio was of the belief that Barthez was coming out to meet him, therefore forcing him to strike first time, yet Barthez only came halfway. “If I could relive the chance again, I would let the ball bounce and give myself time,” he said, “but that was the story with my Italy at World Cups, a little unlucky.”

Penalties were the only thing that would separate the two teams, and so Italy lost their third penalty shootout of the ‘90s. Baggio would score first, further cleansing the memory of Pasadena. Albertini and Di Biagio, who, along with Vieri, had been Italy’s best player throughout the competition, would have their names written alongside Roberto Donadoni, Aldo Serena, Franco Baresi, Daniele Massaro and Baggio as players who missed in shootouts.

It was the most bitterest of pills for Baggio, he’d played in 16 games at three World Cups and only lost one in 90 minutes, against the Republic of Ireland.

Pride, passion and tears: Italy’s 1990 World Cup campaign

Aftermath

In the wake of the quarter-final exit, the usual soul-searching over Italy’s football identity began. Many of the French side were hugely critical of Italy; with Zidane making the case that ‘Italy had the best strikers in the world, but didn’t know how to use them’. “You cannot have Vieri and Del Piero on the pitch and not play for them,” Zidane remarked. Didier Deschamps described Italy’s performance as ‘old’.

Del Piero was crucified by the Italian press, with La Repubblica likening his performance against France to an ‘empty plastic bag being blown around in the wind’. To his credit, Del Piero was candid about his performances, saying, “France ’98 won’t hold happy memories for me, I didn’t do what I wanted, for myself and for the team.”

There was a sense that Del Piero couldn’t cope with the shadow of Baggio looming large, that his every mistake would be scrutinised and after every bad game calls made for Baggio to replace him. Even in the Conegliano, Del Piero’s birthplace, a vote taken during the tournament suggested people wanted to see Baggio rather than their famous son.

This was an issue acknowledged by Baggio, but knew it was something he had little control over, “I was always loved by the Italian people,” he said in 2011. This was an issue that would rear its head in the run up to Japan and South Korea in 2002, with players, again, reportedly telling Trapattoni not to bring Baggio as the 23rd man. And Trap, despite public petitions and even pleas from politicians to bring him, listened. He didn’t fancy having to face a barrage of Baggio questions during the tournament.

Maldini came in for fierce criticism, with many pointing to his – even by Italian standards – absolute lack of willingness to win the quarter final against France. Maldini’s sheer stubbornness in persisting with Del Piero, when it was clearly evident that Baggio was in better shape and in better form, also drew ire. The stance from Maldini was admirable, by showing relentless faith in Del Piero, that eventually he would come good. But, you almost get the sense that Maldini was cutting off his nose in refusing to start Baggio. Maldini would resign shortly after the tournament.

In many ways, France ’98 represented watershed moments in both their careers, with neither reaching the same heights. Del Piero’s 1998 wouldn’t get any better, his form in the opening months of the 1998/99 season followed that of France ’98, before sustaining that injury in Udine. His stock plummeted to such a level that he finished 16th in the 1998 Ballon d’Or ranking. Had the award been given halfway through the year, he arguably would’ve won it.

Baggio had agreed to join Inter at the beginning of the World Cup and, despite the odd moment of genius, the decision to join the crazy house of ‘90s Inter proved to be disastrous. Niggling injuries and Inter reaching peak-Inter by sacking three coaches in six months led to Baggio losing his place in the Italy squad. His last competitive game for Italy came in March ’99. The pair scored 43 league goals before France ’98. The following season they scored seven.

Del Piero would go through another staffetta at the 2002 World Cup, with Francesco Totti on the other side of the ring. But, the debate lacked the intensity of the Baggio/Del Piero relay, for he wasn’t close to resembling same player after returning from injury. His added muscle, needed to rebuild his knee, had taken away from his explosive agility and devastating pace, and the no.10 position was rightfully Totti’s. Del Piero now had to settle for Baggio’s old ‘sparring role’.

Del Piero would go on to have a strange relationship with the national team, and in many ways he was the anti-Baggio; he saved his best performances for black and white. Baggio almost transcended club football and everything that comes with it. There arguably hasn’t been a more popular Italian player in the last half century.

Despite going further in 1990 and 1994, the 1998 squad was the arguably the finest of the three. And with a more adventurous, more daring coach, one with more inclination to attack, Italy could’ve added their fourth star sooner than 2006. Baggio is certainly in that line of thinking.

For Italy, France ’98 represents the tournament of a resurrected hero, the downfall of another, the pressure that comes with managing the national side, and, ultimately, one of bitter regret.

Words by Emmet Gates: @EmmetGates

Very well written article…I’m still trying to digest that I saw Baggio sitting on the bench with the number 18!

You and me both. The continuous undermining of Baggio’s career by players and coaches is enough to make me hate to be Italian. This man should have been treated like Maradona. Captain’s band and the number 10.

I would also argue the ’98 lacked the experience of the 94 and 90 team. After all, 1994 Italy was the Champions League winner, AC Milan without Savicevic and Boban. Replace them with Baggio and Berti and you have an arguably better side.

a great read. thx a million.

great memories for me. the 98 was the best team from 90,94,02 and maybe better than 06 in term of players but 06 win on tactics. Baggio play well doom the ghost of 94. Del Piero didn’t play to his abilities due to injury before the world cup.

great article thank you very much.you have tell the whole story i ve lived all those intense moment being child and having only teletext in italian as sources. it was a little bit madness that a player like baggio was treated on that way by his coaches as it was written above he deserved the same treatment as maradona zidane r9 and messi had “the keys of the team” unfortunately italian coaches were too confident on their way that they all pay it with eliminations. hopefully pirlo took this relay and assumes it in 06.

none of totti and del piero has done what baggio or pirlo gave to the team serenity talent and decisiveness.