In 1925, Italy was in the grip of fascism. Following a campaign of scare tactics and violence that began with the 1922 March on Rome, Prime Minister Benito Mussolini, known as ‘Il Duce’ (the leader), began dismantling the constitution to establish a dictatorship.

Meanwhile, calcio continued to flourish. Since its inception in 1898, the Italian football league had progressed from a four-team one-day tournament, first won by Genoa, to regional divisions with the winners competing for a national crown. Separate championships, for foreign players living in Italy and Italian born players, were also formed and the system of playing home and away was introduced.

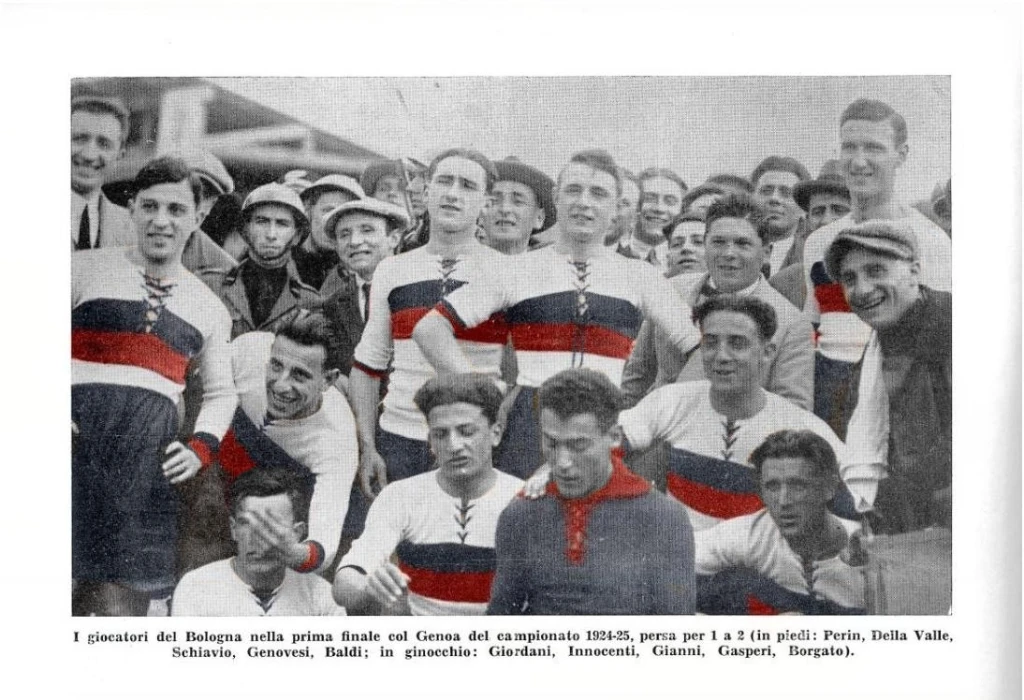

Fast forward to 1925 and the Italian Prima Divisione was in full swing. In Northern Division Group A, Genoa triumphed over Modena by a single point while in Group B, Bologna finished above seven-time champions Pro Vercelli to set up a two-legged playoff final.

In a close-fought first leg at the Stadio Sterlino in Bologna on May 24, Genoa prevailed 2-1 thanks to goals from Alberti and Cargo. Seven days later, the two sides met again at the Stadio Luigi Ferraris in Genoa. Bologna, yet to win a Scudetto in their 26-year history, faced the daunting task of turning around a 2-1 deficit against the nine-time Italian champions.

Giuseppe della Valle struck first for the visitors to level the aggregate scoreline before Aristodemo Santamaria restored Genoa’s advantage. The side from Emilia-Romagna responded again, Giuseppe Muzzioli scoring the winning goal to level the tie at 3-3. With no penalty shootouts during this era, a tie-break was arranged on neutral ground in Milan.

Among the 20,000 fans who attended the match in Milan on June 7 was a Bologna follower named Leandro Arpinati. He was founder of the second fascist movement in the city and had connections with the Italian Football Federation. He was also friends with Mussolini, the two having previously collaborated on the socialist newspaper La lotta di classe before their moves towards fascism.

It was not uncommon to see high-profile fascists attending football games. Mussolini’s regime went to great lengths to champion Calcio, both as a vehicle of national identity and a conduit for spreading political ideology. At times, they directly interfered in Italy’s national game, especially when it suited them.

Mussolini and Calcio: Fascism’s legacy in Italian football

The referee for the first Genoa-Bologna tie-break game was Giovanni Mauro, a former Milan and Inter player who worked as a lawyer but was still asked to officiate important matches.

On the field, Genoa took command and went into halftime with a 2-0 lead. In the second period, a resurgent Bologna came close when Muzzioli’s powerful close-range effort was turned away for a corner by Genoa keeper De Pra.

Then came the moment of controversy. A group of Bologna fans led by fascist Blackshirts surrounded referee Mauro. They claimed the ball had gone through a hole in the net before going behind for a corner and a goal should be given. After 15 minutes of protest and intimidation, the referee bowed to pressure and awarded the goal.

With just eight minutes left, amid growing tension, Bologna’s Schiavio scored the equaliser to take the game to extra time. However, following a conversation with the referee, Genoa refused to play on.

The official assured players and staff he would speak to the Federation and have the match awarded to the Ligurian side, stating he had only carried on to avoid further trouble and potential violence. Indeed, under Federation rules, a pitch invasion was punishable by forfeit.

However, Mauro went back on his word. Under pressure from Leandro Arpinati, he mentioned the pitch invasion in his match report but assigned no blame to either team. As a result, another replay was scheduled, this time in Turin.

The Story of Leandro Arpinati and his chequered history in Italian football

The second replay proved to be a more civilised contest. Bologna took the lead through Schiavio after 11 minutes, but were later pegged back by a strike from Genoa forward Edoardo Catto. With the scores level after 90 minutes the game went to extra time but neither side could find the breakthrough.

A well-tempered encounter on the field was followed by ugly scenes off it as fans clashed at Turin’s Porta Nuova train station. Two to 20 gunshots were reported from Bologna’s train but fortunately only two people were injured and none fatally.

Following this sour chapter, politicians suggested cancelling the tournament or expelling the Northern Division finalists and awarding the Scudetto to the Southern Division Champions, Alba-Audace of Rome.

However, after much deliberation, it was decided the matter be decided on the pitch. Another replay, to be played behind closed doors, was scheduled in Turin, but the local authorities refused, citing crowd trouble in the previous fixture. The Federation hastily arranged another behind-closed-doors match in the Vigentino suburb of Milan.

Two months and 14 days after the first leg of the first playoff game, it was only fitting that the story ended with more controversy.

Originally, the teams were told the fixture would take place in September giving the players time for a break after a long season. However, the date was switched to August 9, with a 7:00am kick-off time. Arpinati was informed in advance through his contacts in the Federation and Bologna were able to cancel their holidays and keep their players fit for the match.

Genoa, on the other hand, were only told in the days leading up to the game and had to call many players (now lacking match fitness) back from their holidays at short notice. The location was also kept secret until the last minute with the Press reporting, under instruction, the game would be played in Turin.

Unsurprisingly, with the odds stacked in their favour, Bologna won the game 2-0 thanks to goals from Pozzi and Perin, this despite them being down to nine men by the final whistle.

After five games, Bologna (and Arpinati) had won the Northern Division and went on to play Southern Division Champions Alba for the national title. It was widely accepted that the quality teams were in the North and a first ever Scudetto would be a formality for I Veltri. And so it proved, Hermann Felsner’s men winning the home leg 4-0 with goals from Della Valle (2), Schiavio and Perin, before wrapping up the title with a 2-0 second leg victory, Della Valle again on target, Rubini scoring the second.

The scope of Arpinati’s influence in the championship dubbed the ‘Scudetto della Pistole’ (the Scudetto of pistols) is still up for debate. Genoa fans painted Bologna as thieves while the victors rubbished such talk as conspiracy theory.

A year later, Leandro Arpinati became the unelected Mayor of Bologna and President of the Italian Football Federation. In the 1926-27 season, Torino won the Scudetto after beating Bologna in the final, but were stripped of the title following a match-fixing incident known as the ‘Allemandi Scandal’. Now in a position of power, Arpinati couldn’t be seen to be favouring his team, so instead of awarding the title to Bologna, he declared the 1926-27 season winnerless.

Finally, spare a thought for Genoa. Having won nine Scudetti, the Grifoni went into the 1924-25 season aiming for a 10th title and the right to sew a gold star onto their jerseys. That honour was ripped from their grasp and has eluded them to this day.

Words by Wayne Edge: @oasis1711