The headlines after Serie A’s first Boxing Day fixtures in 47 years could not have been further from what its schedulers intended. What should have been a showpiece event for the league, as it staked its claim as a resurgent offering for global viewers during the holiday period, was instead overshadowed by yet another blotch on Italian football’s rather dark record for discrimination and violence.

After a coming together of Ultra groups near the San Siro left one dead and a number of others injured, the evening match between third-placed Inter and second-placed Napoli produced more ugly scenes within the stadium. Napoli’s Kalidou Koulibaly, widely thought of as the best centre half in the division, was subjected to numerous racist ‘buu-buu’ monkey chants emanating mainly from, but by no means exclusive to, Inter’s curva nord.

In the 80th minute, after of a typically imperious display, the Senegalese nudged Inter winger Matteo Politano off his stride during a dangerous looking counter-attack and rightly picked up a booking. Down came the derision from the Inter faithful and Koulibaly, clearly wound up, sarcastically applauded the referee – a gesture to which Serie A referees generally give a yellow, and which got Koulibaly his second.

Whether or not the racist abuse was the direct cause of Koulibaly’s actions is open to debate but either way, the fact that Inter’s Lautaro Martinez clinched the game’s only goal 10 minutes after the sending off, and from a position in which the defender was likely to have been, ensured the racism was a focal point of resulting coverage.

Napoli coach Carlo Ancelotti said he’d asked three times for the game to be suspended, and warnings that it would be if the chants persisted were transmitted over the stadium’s PA system. It seems highly likely that the violence that preceded the match was in the minds of the match officials and police at this point, who didn’t want another public order issue on their hands.

The suspension of matches does offer some obvious benefits; putting an immediate halt to the abuse by removing the victims from view, denying the perpetrators of further entertainment and sending a clear message that football will not be played in such conditions. However, aside from its potential to incite violence among those in the crowd that way inclined, it also offers the possibility for supporters unhappy with events occurring on the pitch to get proceedings stopped for their team’s benefit. It’s been used on multiple occasions with little evidence of lasting success.

Many who watched events unfold from afar have suggested that simply identifying and punishing individual offenders is the only effective and just way of dealing with the problem. This should certainly be done wherever possible, and there’s a good case to be made that CCTV surveillance in Italian stadia needs to be enhanced. However, those who had the displeasure to be at San Siro on Boxing Day or have witnessed other similar episodes around Italy know that most of the time, this just isn’t possible. These ‘buu-buu’ chants take the form of an undiscernible growl surrounding the field of play, clearly audible and widespread but without a clear origin that cameras could easily hone in on. The access points at many outdated Italian grounds like San Siro are such that sending police in would be fruitless and could well result in clashes in the curva, whose residents do not take kindly to the authorities setting foot on their ‘turf’.

What the Italian Football Federation opted for instead were stadium bans – two Inter home matches to be played behind closed doors, and one additional game without the curva nord. The sanctions have been met with general acceptance by right-minded observers, albeit with a general lack of certainty as to exactly what level of abuse constitutes what level of punishment (Juventus were punished with just a curva closure for less widely reported racist abuse earlier in the season). It is, however, a response that has been utilised repeatedly in the past and which clearly isn’t acting as an effective deterrent. Perpetrators of the abuse will watch the games from the warmth of their homes or local bars and return unchanged afterwards, while many of the blameless matchday staff and vendors go without the day’s income and the league’s image is further toxified by matches joylessly played in front of empty seats. The fact that the majority of non-racist supporters are also punished is an obvious additional downside.

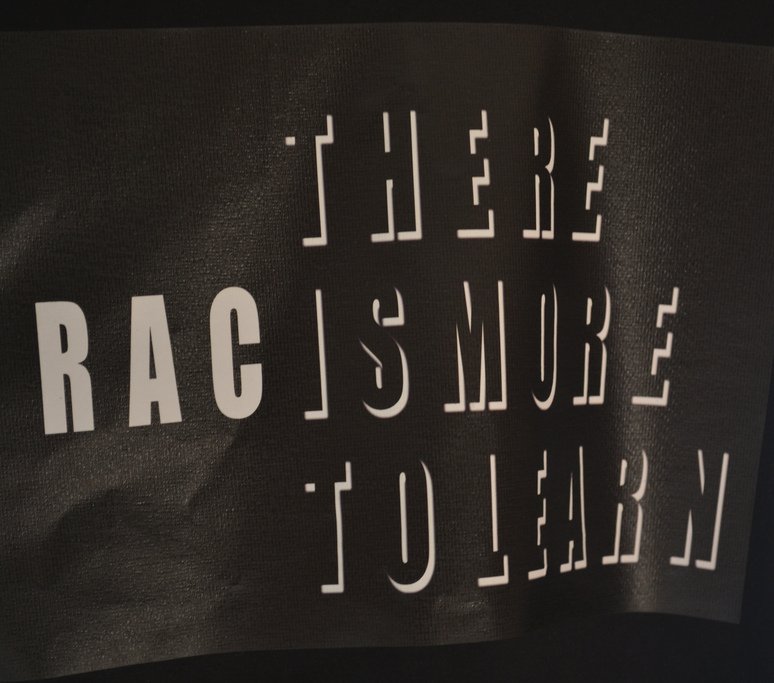

Face to face with the beast: Calcio and racism

As I argued in a piece written for TGU after the last time I experienced racist chanting at San Siro back in 2016, the motives behind this form of abuse is, to a large extent, tactical. Inter fielded two African players on Boxing Day in Keita Balde Diao and Kwadwo Asamoah but unsurprisingly, none of the abuse was aimed at them. The chants are clearly a device used to get under the skin of opposing players. Racist behaviour is not deemed by less enlightened Italian football fans as a line which is not to be crossed.

The only feasible way forward, therefore, is for the authorities to remove that tactical incentive by dishing out points deduction to clubs whose supporters have been found guilty on a large scale – a measure which would deter the majority of perpetrators while rightfully rendering those who persist as pariahs among their fellow fans. It can be carried out retrospectively and proportionately, not risking the safety of police or fans at the game or forcing officials into decisions above what they should have to expect to deal with.

This would by no means be a perfect solution. Clearly, players as well as spectators who played no part in the offences would be penalised, and a rather uncomfortable link between a team’s performances and a minority of their fans’ behaviour would manifest itself on the league table. However, given the likeliness of success that this measure would have, those arguments inherently imply that these transient issues are more important than stamping out racism, which isn’t a position Italian football should or can afford to take. Some have suggested that it would create opportunities for supporters to attend rival team’s matches and shout abuse in hopes of costing them points and while this possibility would need to be policed, such a conspiracy coming together in required numbers without becoming public knowledge is difficult to imagine.

Points deductions would not, of course, make any dent into the root cause of the problem which is the deep-seated cultural racism entrenched in Italian society. Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini’s comments after the match that he didn’t see the difference in severity between racist and non-racist insults offers a worrying insight into prevailing attitudes, but which would come as little surprise to anyone following recent Italian political developments.

While football may not be able to rid a society of its ills, it does have a responsibility to keep itself free from mass spectator hate crimes such as that which took place in the San Siro on Boxing Day. That responsibility must weigh more heavily on the shoulders of Italian football’s governing bodies than it currently does.

Words by Tom Guerriero-Davies: @TomGDella