Such was the strength of political divide in Italy from the late 1960s to the late 1980s, the country became a symbolic border between the Eastern and Western Blocs; a cold war battleground where a generation of politically charged youths were recruited into a campaign of terror supported by international security, intelligence and counter-intelligence forces. During this period, known as the “Years of Lead,” more than 400 people lost their lives and the echoes of this unofficial civil war still reverberate today.

Throughout those years, it was not uncommon for political groups to use sporting and music events to carry out recruitment campaigns. Leaflets were handed out on football terraces as Ultra groups linked to political factions sought to boost their numbers. But on the Curvas, groups from different political ideologies rarely mixed. In fact, they usually gathered in different areas of the stadium, separated by fences or barriers.

In music venues, however, there were no organised Ultra sections and no barriers or fences. Concertgoers of all ages and political persuasions were funnelled into venues and stood shoulder to shoulder, creating a breeding ground for political tension.

When English rock band Led Zeppelin headlined an all-day festival at the Vigorelli Velodrome in Milan on July 5, 1971, communist, anarchist and fascist groups used the opportunity to distribute flyers outside the venue. And before the event had even started, police had clashed with several smaller groups (known as Portoghesi) who were renowned for trying to force their way into events without paying.

Inside the venue, tensions were already mounting and by the time the first support act took to the stage, further scuffles had broken out. As the audience grew tired of waiting for the headliners, the atmosphere turned even nastier, prompting the other support bands to cut their sets short.

The presence of 2,000 police officers did little to curb the violence. As the English rockers took to the stage, more fighting had broken out and the velodrome was already a haze of tear gas. Just 40 minutes into their set, Robert Plant and his bandmates were forced to retreat to their dressing room and barricade themselves in. The trouble continued outside the arena as rioters clashed with the police in side streets for several hours.

Roadies recovering the band’s equipment from the stage braved a shower of petrol bombs, bottles and stones and many were left injured. The whole entourage eventually fled under police escort to the sanctuary of their hotel. Unsurprisingly, the band never played in Italy again.

Amazing as it sounds, this type of incident was common during the period. High-profile concerts featuring Chicago, Rolling Stones and Humble Pie also ended with tear gas attacks from the police. And anyone who went to a concert did so in the full knowledge that violent incidents were likely.

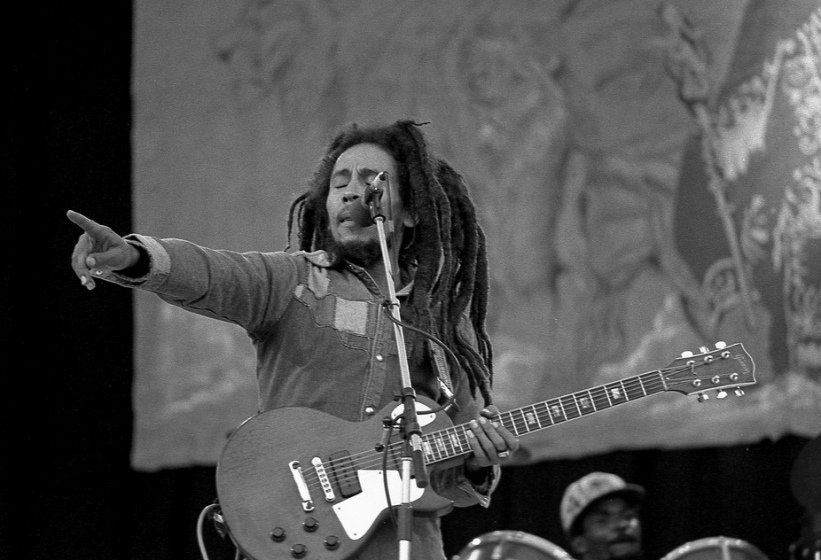

It was against this backdrop that one of the most remarkable events in musical history took place on June 27, 1980, in Milan. An event that proved to be a watershed moment for the generation raised in the Years of Lead. Bob Marley played live at the San Siro.

Marley had a history of uniting opposing political factions. In 1978, at the One Love Peace Concert in Kingston, Jamaica, the singer got Prime Minister Michael Manley, of the PNP; and rival Edward Seaga, of the JLP, on stage to join hands and declare an end to the political violence that had plagued the country. Marley himself had been shot just over a year before.

The gig in Milan was a huge risk for organisers. Previous concerts with crowds of just a few thousand had turned into full-blown riots. This time, they were bringing around 100,000 youngsters together at a time when political tensions were at their highest. The previous year had seen the highest number of assassinations since the era of darkness began in 1969.

With many big-name bands refusing to play in Italy, the demand for Bob Marley tickets was enormous. For many of those who attended, it was more than just a concert, it was a rite of passage. It was a chance to show that their generation was ready to swap violence for peace.

Before the music even began, there was a festival atmosphere. A diverse crowd mixed happily under the searing sun, the air hazy with weed smoke. There were no leaflets, no politics, just the sense that some kind of divine being was about to descend into the arena and unite all who were present.

Italian bluesman Roberto Ciotti set a mellow tone for the day, plucking his way through a set of Mississippi Delta-inspired tunes. Next up was Naples-born Pino Daniele who wowed the crowd with an eclectic set of world music before Scottish funk outfit Average White Band got the party vibe going.

By the time the lights went out and the “Marley Chant” began, the crowd were at fever pitch. A riot had started. But this time it was different. This was a riot of colour, a riot of love, a riot of redemption. As the silhouette of a dreadlocked figure materialized in the centre of the stage and the first shout of “Jah! Rastafari” blasted from the sound system, the roar was deafening. A spirit had awoken. After a decade of darkness, a light had descended to fill the void.

That night, Marley reached inside everyone in the stadium and stirred their spirituality. He reduced every person to vibrating skin and bone – pure, and free of hate. This broken generation of young Italians were uplifted by his music, inspired by his presence. They felt a connection to Africa. To Jamaica. To the World. When he preached the words “Get up, stand up” during the encore, every member of the crowd was already standing taller than they had ever done in their lives. This was their night. This was their coming of age.

Less than a year later, Bob Marley died of cancer. At his funeral, Jamaican Prime Minister Edward Seaga’s words resonated with each of the 100,000 who were present in Milan:

“His voice was an omnipresent cry in our electronic world. His sharp features, majestic looks, and prancing style a vivid etching on the landscape of our minds. Bob Marley was never seen. He was an experience which left an indelible imprint with each encounter. Such a man cannot be erased from the mind. He is part of the collective consciousness of the nation.”

The violence did not end in 1980. Several weeks later a bomb planted by neo-fascists killed 85 people and wounded 200 more at Bologna’s railway station. But that year; that day; that concert, marked a turning point for Italy’s disaffected youth. The number of assassinations fell drastically and many political groups disbanded leaving just a few hardcore cells still active. By 1988, the war on the state was declared over.

There have been countless memorable performances at the San Siro since – both musical and sporting. But none can claim to have had the social, cultural and political impact of the 19-song set performed by the man from Kingston, Jamaica, on June 27, 1980.