I’ve lived all my adult life in Italy but the first time I saw an Italian team play in the flesh was as a teenager in my home town of Carlisle. The date was June 7 1972, the occasion Carlisle United v. AS Roma. It was a group match in the short-lived, long-forgotten, end-of-season Anglo-Italian Cup, the brainchild of Calabrian proto-soccer agent Gigi Peronace. The competition eventually folded due to ill-discipline on the field and apathy off it. It caught the imagination of no one: no one except me, that is.

Like many football lovers, I support two teams: the one of the town I was born in and one of a choice of two in the city where I’ve spent most of my life, Turin in Italy. Carlisle United and Juventus, two clubs that couldn’t be more different for lineage, culture and prestige: the first chose me, I chose the second.

As a schoolboy, for reasons beyond my comprehension, I fell in love with Italy, with its art, its history, its literature and, above all, its football. I was to go on to read Italian at university but in 1972 I was still trying to teach myself the language by listening to cassettes, following BBC television courses, watching films and attempting to read whatever came my way: from the novels of Moravia and Pavese to the opies of Il Corriere della Sera or La Stampa – especially the sports pages – I occasionally managed to pick up at the local John Menzies distribution depot. What I devoured the most was my team-by-team statistical guide to Serie A, Vademecum al campionato, a start-of-season supplement to the copy of the Guerin sportivo football weekly my sister had brought back from her summer holidays in Rimini the year before.

I had never been to Italy, still less seen an Italian team play. It was Roma who plugged that gap in my life. For the first time since building Hadrian’s Wall, the Romans were back in Cumbria, not in chariots but in a luxury coach. My dad and I were among a handful of fans who watched it pull into the car park at Brunton Park, or ‘The Brunt’ as he used to call it.

First off, smiling broadly, was the legendary Roma Mister Helenio Herrera, better known as ‘HH’ (pronounced Acca Acca in Italian) or, alternatively, as ‘il Mago’ – the Wizard. He was wearing a cream-coloured gabardine suit and dark glasses, and had leathery skin, sharp features and frizzy jet-black hair. He looked like an extra from The Italian Job or, alternatively, from a Grecian 2000 commercial.

In reality, the Mago didn’t dye his hair at all. According to his widow Flora Gandolfi, all he ever put on it was brilliantine. That’s a morsel of knowledge I owe to the fact that, though I would never have imagined it as a schoolboy in Carlisle, I was later to make the acquaintance of Donna Flora herself– in Italy. And in addition to idle chit-chat, she also gifted me with a copy of Tacalabala, a curious little self-published anthology of the multilingual motivational slogans the great man posted on dressing-room walls from Paris to Madrid, from Barcelona to Milan: Nunc ate rindas (Never surrender), Lutte avec joie et calme (Fight with joy and calm), La maggior parte degli ostacoli sono di natura mentale (Most hurdles are in the mind) – that sort of thing.

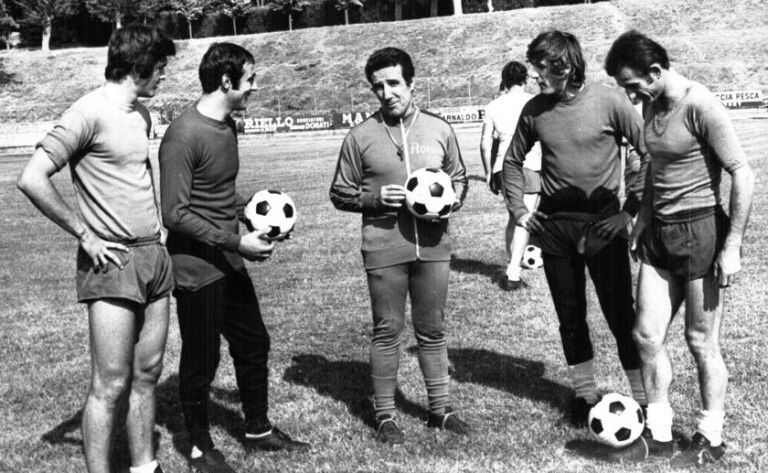

Herrera was followed off the bus by the players, unsmiling and bored-looking. Thanks to my Vademecum, not only did I recognise them all, I also knew their personal details by heart – and gained familiarity with the metric system at the same time. The sight of captain Franco ‘Ciccio’ Cordova sent my brain onto automatic pilot: ‘Born in Forlì in 1944, 1.80 meters, 77 kilos, married to TV presenter Simona Marchini, daughter of former Roma president, Alvaro Marchini …’

Cordova was later to play twice for Italy but other Roma players had already been capped: the stopper Aldo Bet, the libero Sergio Santarini and the right-winger Renato Cappellini, who had also appeared in Herrera’s Inter side destroyed by Celtic in the 1967 European Cup final in Lisbon. Otherwise, the team was a mixture of promising youngsters such as Giorgio Morini, who was later to win a scudetto with Milan, Dino Spadoni and Angelo Orazi, and hardened Serie A pros such as full-back Francesco Scaratti and goalkeeper Angelo Ginulfi, both Roman born-and-bred.

As the Italians trailed into the dressing rooms in their elegant club suits and ties, my dad nodded in the opposite direction. ‘Look what the wind’s blown in,’ he said. At the other end of the car park, the star of our team, Stan Bowles, was stepping out of the beaten-up Ford Transit he had parked against somebody’s backyard wall. He was wearing a stained T-shirt and a pair of torn jeans, and carrying his boots in a plastic carrier bag. Typical Stan, as inept off the field as he was talented on it. A gambling addict, he used to bet at the same bookies as our next-door neighbour Jimmy Wilson, just down the road from our house. One Saturday when my dad and I were setting off for the match – which he always referred to as ‘the appointment with fear’ – we met Jimmy on his way home. ‘No need to hurry,’ he said. ‘You’ll be at Brunton Park well before Stan Bowles. He’s still in Ladbroke’s waiting for the result of the 2.15 at Market Rasen.’

As he himself admits in his unimaginatively titled Stan Bowles: The Autobiography, Stan was hopeless with cash. ‘If you bought a cemetery,’ his mother apparently once told him, ‘people would stop dying.’ When he left Carlisle for Queens Park Rangers at the end of that summer, it was Stan who owed the club money, not vice versa.

The game against Roma was the second of two. Nobody in Italy believes me when I tell them the tale, but in the first, played at the Stadio Olimpico in Rome, Carlisle had beaten Roma 3-2. ‘You could have counted on the fingers of one hand the number of Carlisle fans who made the trip,’ writes Stan Bowles. ‘They were the pasty-faced ones in the crowd wearing scarves and woolly hats wondering where the snow had gone.’ At Brunton Park there were 12,000 pasty faces against ‘eleven bronzed prima donnas’, as the press used to describe Latin teams in those days.

Stan is laying it on thick when he writes that, ‘Roma were one of the best clubs in Europe, if not in the world, at the time’, but playing them was nonetheless a major chapter in the history of Carlisle United. Though we had already played friendlies at The Brunt against Sparta Prague and MSV Maastricht, my dad, who was well into his fifties by then, insisted on describing the Roma match as ‘The first major international challenge of my football supporting career’. It was competitive after all, even if the competition was the Anglo-Italian Cup.

Remembering The Anglo-Italian Cup

When the teams took the field – the Giallorossi in white for the occasion – they lined up at the centre of the field. We’d never seen anything like this before. My dad elbowed me and winked. ‘Classy stuff, eh?’ he said.

The match ended 3-3. Carlisle led 2-1 at half-time with goals from Ray Train and Chris Balderstone, who had what was known t as a cultivated left foot and was also a professional cricketer, twice opening the batting for England against the West Indies. The scorer for Roma was Ivo Banella, who only ever played one match for them in Serie A.

Five minutes into the second half, Bobby Owen outjumped Bet (1.85 metres, 83 kilos, by the way) to clinch Carlisle’s third goal with a glancing header. An own goal from Tot Winstanley and a late strike by Cappellini earned Roma the draw.

Carlisle goalkeeper Alan Ross is reported as saying that, ‘That must rate as one of the best games ever seen here,’ but I beg to differ. Carlisle went about their business, turning on the push-and run football they were famous for at the time, a style of play that was to take them to the First Division two years later with virtually the same group of players, minus Stan Bowles plus Hughie McIlmoyle (born in Port Glasgow, five foot-ten tall), back for his third stint at the club. They were up for it, but Roma weren’t. It was only thanks to their superior quality and a dip in Carlisle’s energy levels in the final minutes that the Italians managed to equalise. Their minds were obviously elsewhere, probably on some beach in the Mediterranean. As was that of Acca Acca, who sat in the director’s box and beamed throughout.

In those days Italian players were viewed in the UK as a European version of the Argentines. The latter were ‘animals’, the former were thugs who practised catenaccio. But that night in Carlisle, Roma were neither dirty nor defensive. It was more as if they were playing in a match between scapoli e ammogliati (bachelors and married men), which is what Italians call a casual kickabout.

I later saw Ciccio Cordova many a time at the Stadio Comunale in Turin. He was a brilliant technician, playing a pivotal scheming role for Roma, then, following a sensational move across the city, for Lazio. In Carlisle, he never left the centre circle, hardly broke into a sweat. Herrera, obviously hadn’t written another of his aphorisms, ‘Camminare lentamente stanca’ (Walking slowly is tiring), on the dressing-room wall at Brunton Park.

According to Corriere dello Sport reporter Massimo Lo Jacono, the Mago said after the match that, ‘From a technical point of view, I can’t be proud of a draw against an English Second Division team but Roma’s ability to get back into the game was amazing’. Lo Jacono himself wrote that the Roma performance was ‘a triumph of willpower, tenacity and pride’. We must have seen different matches.

He also spoke about adverse ‘environmental factors’ such as ‘the pouring rain that made the small town’s already cold air colder’. Funny that, my recollection is of a balmy summer’s evening. Had I been dreaming? Had I imagined it?

My hunch is that Lo Jacono never came to Carlisle at all. The dateline for his piece is ‘London June 8’ and it just happens that, in addition to being a sports reporter and a Roma fan, he was also, under the outlandish noms de plume of L.J. Mauritius and Megalos Diekonos, a writer of science-fiction. Maybe it’s he who did the imagining.

Roma went onto win the Anglo-Italian Cup, incidentally, beating Blackpool 3-1 in the final at the Stadio Olimpico.

Words by John Irving: @irving_john