‘There are ten thousand fans waiting at Fiumicino,’ announced the captain of the plane carrying the Italian team home from Mexico City on Monday June 21 1970, the day after their 4-1 World Cup final defeat against Brazil. ‘It would be better to change course and land at Ciampino.’

Artemio Franchi, president of Federalcio, the Italian football federation, would have nothing of it. ‘We can’t deprive the fans of the joy of embracing the players,’ he said. Little did Franchi know that the same Roman fans who had partied through the night in the wake of Italy’s epic 4-3 semi-final victory over Germany the previous Wednesday, bathing in fountains and honking their horns in motorcades, had now grown hostile.

Euphoria had turned to rage. When the plane landed, one member of the delegation, Franco Carraro, then president of AC Milan, described the atmosphere at the airport as ‘that of a civil war’.

Nobody outside Italy had expected Italy to beat Brazil and nobody in Italy had expected the team to reach the final. And surely it was no disgrace to lose it against a team generally recognised to be ‘from a different planet’. Before the tournament, Franchi himself had said he would have been happy to reach the last eight.

Italy’s record in post-war World Cups had been disastrous. In 1950 in Brazil and 1954 in Switzerland they had gone out in the first round of the final stages and had failed to qualify altogether for Sweden in 1958. In Chile in 1962 they had been sent packing by the hosts in the infamous ‘Battle of Santiago’, and in 1966 in England they had been ignominiously knocked out by North Korea.

That year, understandably aggrieved by what was effectively a national football tragedy, fans had pelted the team with rotten tomatoes on their arrival at the Cristoforo Colombo airport in Genoa. But in 1970 Italy had come an honourable second against Pelé & Co. They seemed entitled if not to a heroes’ welcome, at least to a modicum of respect.

What had happened in the space of four days to sour the mood of the fans? The answer is that after coming off the bench to score the winning goal in extra time against Germany, Gianni Rivera, the ‘Golden Boy’ on whom the nation pinned all its hopes, had been allotted a measly six minutes on the field at the end of the final, when Italy were already two goals under.

The villain of the piece, the man deemed responsible for allowing this to happen, was the head of the Federcalcio delegation in Mexico, Walter Mandelli. ‘Viva Rivera, Mandelli in galera!’’ (Long live Rivera, Mandelli go to jail) read the rhyming slogans on the fans’ banners at Fiumicino.

Fifty years have gone by since then and everyone remembers Rivera, but what about Walter Mandelli? He was the co-protagonist of an unforgettable chapter in the history of the Azzurri, but who remembers him today?

I do, because I used to teach him English in Turin. It was the early 1980s and he was in his late fifties, a thickset balding man of average height with a square face and thick-rimmed round glasses. We were at cross purposes: he wanted to learn English and I wanted to talk about Mexico, his least favourite topic of conversation.

Mandelli, who died in 2006, had an eventful life. His father was a Fiat worker who subsequently set up on his own and established a steel foundry in the Turin suburb of Collegno, his mother was a laundress. As a young man he was a member of the PCI, the Italian Communist Party, and helped organise the first national Festa dell’Unità, the annual festival sponsored by the party newspaper, in Turin in 1952. Disillusioned by the Soviet Union’s invasion of Hungary in 1956, he left the party and devoted himself to the family business.

It was in that period that he became a friend of Umberto Agnelli, with whom he used to enjoy skiing weekends at Sestriere, the mountain resort developed by the Agnelli family in the 1930s. When Umberto, still only 23, was appointed president of Juventus in 1955, he asked Mandelli to join him as vice-president.

‘My dad was a Torino supporter but for me there was only Juventus,’ he told me. ‘Umberto infected me with his enthusiasm and I stopped going skiing to help him out. I knew I’d have to roll up my sleeves but I also knew that I would have fun.’

One of his first duties was to supervise the Juventus transfer market and in 1957 he played a key role in signing John Charles and Omar Sivori. Following a tip-off from proto-football agent Gigi Peronace, he and Agnelli flew to Belfast to watch Charles play for Wales against Northern Ireland and decided to buy him there and then. ‘He didn’t have a great game but we were impressed by his physical strength,’ said Mandelli.

He was less sure about signing Sivori on account of the cost of the operation: 160 million old lire, a record fee for the time. But when Agnelli said, ‘I’m going to buy him anyway,’ Mandelli gave in and the deal went through.

When Agnelli was voted president of Federcalcio in 1959, Mandelli followed him and became president of the federation’s Technical Sector. The new job enhanced his knowledge of the game, so much so that it was he who advised commissario tecnico Ferruccio Valcareggi to make radical changes to the Italy team before the replay of the 1968 European Championship final against Yugoslavia in Rome. The upshot was a 2-0 victory with goals by new boys Gigi Riva and Pietro Anastasi, and Italy’s first international title since the 1938 World Cup.

Gigi Riva: The silence before the thunder

In Mexico in 1970, Mandelli was Artemio Franchi’s factotum, acting as a ‘minder’ for Valcareggi and overseeing relations with FIFA and, implicitly – this being Italy – with referees. The hardest part was coping with the factious Italian press, then divided between difensivisti, led by Gianni Brera and Gualtiero Zanetti, proponents of calcio all’italiana, ‘Italian-style’ football based on catenaccio, bolt defence, and contropiede, counterattack, and offensivisti such as Gino Palumbo and Antonio Ghirelli, who favoured creative, attacking football. The feud had been festering for years and the Mexican campaign brought it to a head.

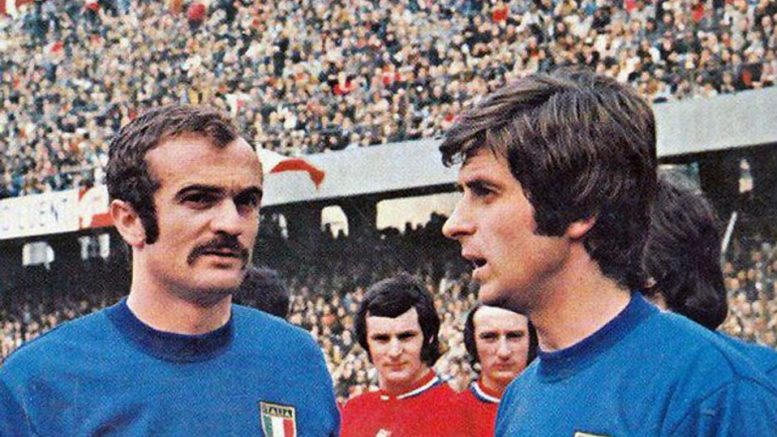

Another divisive rivalry was that between the two darlings of Milanese football, Rivera, captain of AC Milan, and Sandro Mazzola of Inter. For years Mazzola had played as a mobile centre-forward and that was the position he took up in Italy’s final friendly before leaving Europe – against Portugal in Lisbon – with Rivera behind him as regista.

Once in Mexico, he began expressing his desire to play deeper, in a role similar to Rivera’s, thus creating an insidious dualism. The two had never got on personally and now found themselves fighting for the same place in the team.

According to Franco Carraro, it was Gianni Brera who, over a long lunch, convinced Walter Mandelli of the expedience of preferring Mazzola to Rivera. The Golden Boy, he said, was less athletic, less suited to the high altitude of Toluca, where the Azzurri were to play their opening match against Sweden.

Mandelli instructed Valcareggi accordingly and, in the squad’s first practice match in Mexico, Mazzola appeared behind the strikers Roberto Boninsegna and Riva, with Rivera relegated to the reserves.

Smelling a rat, Rivera held an impromptu poolside press conference at the squad’s ritiro, or training camp. ‘I gather they want to do without me, I don’t know why,’ he said. ‘I’ve been first choice so far and I don’t think I’ve played badly in the last few games. It seems to me they want to spread gossip and put me in the reserve team in training in order to provoke me into a reaction, so that they can then drop me for disciplinary reasons.’ By ‘they’ he meant Mandelli. ‘If Valcareggi was running the national team on his own,’ he concluded, ‘certain things wouldn’t happen.’

Rivera’s outburst split the squad. Only his AC Milan teammate, stopper Roberto Rosato, and Riva and Boninsegna, who were counting on his assists, were on his side. All the others wanted Mazzola in the team, especially the defenders, who felt he offered greater solidity in midfield.

‘I prefer Mazzola in that position because he gives us more rhythm’ said winger Angelo Domenghini, bluntly. ‘Rivera? He’s a great player, technically the best in Italy. But in a Word Cup you need determination and athletic vigour.’

When Mandelli heard the tape of Rivera’s statement, he was furious and threatened to put the player home on the first plane home to Italy. Franchi was more diplomatic. He explained to Mandelli that he risked turning Rivera into a martyr and recalled AC Milan manager Nereo Rocco from his summer holidays to placate his captain.

Rivera eventually remained, but so did the dilemma. Valcareggi couldn’t dispense with the services of the reigning Balon d’Or holder entirely – Rivera was, after all, the only azzurro capable of winning a match on his own – but if he restored him to the first team, he would be accused of capitulating to the player’s tantrums.

In the preliminary group, the commissario tecnico was able to defer his decision thanks to Montezuma’s revenge, which struck down a number of members of the squad. Rivera, one of the most debilitated, was forced to skip the first two group games, against Sweden and Uruguay. He eventually came on for Domenghini to offer an ineffectual second-half performance against Israel in the last, in which Italy qualified to meet hosts Mexico in the quarter final.

By the time match day came around, a fully recovered Rivera had the offensivisti firmly behind him and was again laying a claim to a place in the team. It was then that Mandelli came up with a compromise solution: Valcareggi was to resort to a staffetta – literally a relay race, by inference a baton handover – in football jargon, the pre-programmed substitution of two players deemed unsuited to playing together.

France 98′ and the Staffetta: Baggio vs. Del Piero, the race for Italy’s No.10

The plan envisaged Mazzola giving his all to wear Mexico out in the first half, then leaving Rivera to weave his artistry and, hopefully, win the match in the second. To many, Mandelli’s solution, more realpolitik than anything else, appeared to be tactical and technical madness. But Valcareggi took it on board, and it worked.

The experts who wrote the official FIFA Technical Study on the Mexico World Cup were suitably impressed: ‘At half-time Mazzola was replaced by Rivera, a switch which determined the result of the match,’ they wrote. ‘Rivera took the strings of midfield approach play into a firm grasp, and his passes were so well-timed and accurately measured that play was completely transformed.’

Rivera ended up laying on two goals for Riva and scoring one himself. ‘Here was a clear illustration of how a single player by cool reading of the game can harmonize the play of other colleagues round him,’ concluded the FIFA study.

Rivera was less effective when Valcareggi repeated the staffetta against Germany but, as we have seen, he scored the winner and that was enough for the likes of Ghirelli and Palumbo in Mexico and the exultant fans at home. For them, Rivera had to play in the final.

But, again pulling the strings behind the scenes, Mandelli was adamant. Italy had got this far thanks to a solid bloc of players whose cohesion had improved as the tournament had progressed. Mazzola would start the final, he said, but Rivera would certainly come off the bench sooner or later – maybe a bit later than normal, given the eventuality of extra-time.

In the event, Rivera did come on later, much later – too late. ‘With less than seven minutes left, they [Italy] again betrayed their masochistic eccentricity,’ wrote Hugh McIlvanney. ‘To have any relevance Rivera would have needed much longer on the field.’ Incidentally and ironically, of Mazzola McIlvanney wrote that he was ‘unmistakably, the heart of the team … None of the 112,000 people who filled the Aztec Stadium is likely to forget how he played.’

For the offensivisti, Rivera’s six minutes were the last straw. Even as Brazil captain Carlo Alberto was raising the Jules Rimet trophy, they were dipping their pens in vitriol.

‘We were missing the most skilful player our football has produced in the last twenty years,’ wrote Antonio Ghirelli in Corriere dello Sport, before sticking the knife into Mandelli and Valcareggi. ‘The moral lynching of Giovanni Rivera, which Signor Mandelli began even before the tournament started, was completed, scientifically, by Signor Valcareggi in the concluding match.’

The Italian plane landed at Fiumicino at nine o’clock the following night, but it was well past midnight when Valcareggi and Mandelli were able to escape in a police van (together with members of the coaching staff such as Enzo Bearzot and Azeglio Vicini, and Mandelli’s daughter) after seeking shelter from the angry fans in an airport hangar.

Mandelli never spoke to me about the episode but mutual acquaintances told me he emerged from it a changed man. Some said he was nauseated, others traumatised. ‘His life became impossible for three months after that,’ wrote Franco Carraro.

Mandelli resigned from the federation immediately and left football behind him. (The last time he spoke about the game publicly was in an interview in the 1990s, when he put forward the idea of a fusion between Juventus and Torino, but that didn’t win him a great deal of popularity either.)

In the 1970s, he threw himself into business, joining with other entrepreneurs to establish Federmeccanica, the Italian Mechanical Engineering Employers’ Association, and holding directorships with FIAT and Alitalia. When I met him, he was in charge of trade union relations for Confindustria, the Confederation of Italian Industry.

Those were the so-called ‘years of lead’, a period of terrorism and bitter labour disputes. Mandelli earned himself the reputation as a falco, or hawk, for the bosses, though Diego Novelli, the Communist mayor of Turin at the time, acknowledged that he never repudiated his past on the left side of the political fence.

Those were tough times for everyone but my view is that Mandelli regarded bargaining with the unions as a walk in the park compared to addressing the poisonous imbroglio of Italian football, with its entourage of interfering journalists, spoilt players and Machiavellian mandarins.

And talking to him, I learned never to mention Mexico.

Words by John Irving: @irving_john