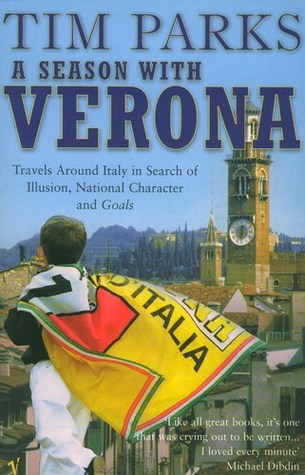

A Season with Verona, the cult classic by Tim Parks, charted the highs and lows of one memorable season spent following Hellas Verona. At that time, they were an unfashionable provincial team, struggling for survival in the Italian top-flight. Of course, it’s far more than just a story about football, delving deep into the very essence of being a fan, while seamlessly exploring various aspects of Italian history, politics, culture and society.

This year marks the 20th anniversary of that epic season that Parks wrote about, so what better time reflect on a great book, an incredible story and a remarkable season:

Hellas Verona had gotten off to a decent enough start. A 1-1 draw away at Bari was followed by just one defeat in the next five games. However, the onset of winter saw a dramatic downturn in fortunes, as Verona drifted ominously towards the bottom of the table. The season reached a dramatic climax, including a 5-4 victory at home against Bologna, a miraculous last-minute victory away to a formidable Parma side, and three points against Perugia on the last day of the season. Then, setting up a nail-biting two-legged relegation tie-breaker against Reggina. I won’t spoil the story by revealing the result here, but there was no shortage of drama.

While football has clearly changed in the intervening twenty years, many of the issues, themes and emotions that Parks explores remain reassuringly familiar to fans today. Even the players and staff have an air of familiarity to them, as, despite Verona’s shortcomings that season, many went on to achieve big things elsewhere.

Although a chunky 447-page-book, A Season with Verona makes for effortless reading, thanks to Park’s engaging style of writing. His detailed descriptions of particular passages of play are beguiling. His lucid accounts of entire matches capture the drama, euphoria, sights, sounds and smells of the Curva, the injustice of the game, the anger, the hatred, the torture and the infantile stupidity of it all, while his pithy observations (“The fan thirsts for injustice”) are disarmingly accurate.

The Club

Twenty years ago, Hellas Verona were an unfashionable provincial side who alternated between relegation dogfights and nerve-shredding promotion battles. For a team that lacked superstars and had little financial clout, Verona boasted a fiercely loyal, sometimes controversial, fanbase. Not much has changed in the intervening twenty years. Since that time, they sunk to the darkest depths of Italian football and continue to fluctuate between the top two tiers of the game. They remain disparaged by many, but defiant and proud of their long history and fleeting moments of glory.

The Stadium

As anyone who has been to the Stadio Marcantonio Bentegodi recently will tell you, not much has changed. In fact, if the truth be told, little has changed at the Bentegodi since the monolithic brute of a stadium was revamped for Italia 90. With a capacity of 39,211 (restricted to 31,045 under normal circumstances) and equipped with an eight-lane athletics track that hasn’t been used in decades, like many stadiums in Italy, the Bentegodi is owned by the city and leased to Verona (and Chievo) for their home matches. It is an arrangement ill-suited to the commercial needs of a modern football club. Over the years, various plans have been floated for its redevelopment, including a recent proposal to demolish the existing stadium and rebuild a state of the art stadium on the current site. To date, nothing concrete has materialised. Despite its deficiencies, it remains an intoxicating place to watch a football match, just as it was back in the day.

Il Presidente

El Pastor, Giambattista Pastorello, Verona’s parsimonious president, was a divisive figure, hated by the fans for his sartorial elegance, air of superiority, Vicenzan origins and, above all, his lack of investment in the club. After the abuse he suffered towards the end of the 1999-00 season, he took a back seat for the 2000-01 campaign. Despite his reputation, Parks found him to be surprisingly urbane and accommodating in person. In a long and colourful career, Pastorello claims to have discovered the likes of Del Piero, Buffon, Mutu, Camoranesi and Gilardino. He took over Hellas Verona in 1997 and enjoyed three years in the Italian top-flight, but after relegation in 2002 his relationship with the Verona fans really turned sour.

In 2006, he sold the club and a year later joined Genoa as its vice-president, securing promotion to Serie A with a young coach named Gian Piero Gasperini. In 2013, Pastorello was indicted for his role in a series of financial irregularities dating back to his time at Verona. Years of litigation followed, leaving his reputation tarnished. His involvement in the game is now limited to scouting activities, and he recently had a hand in the discovery of Musa Juwara – the Gambian winger who scored in Bologna’s victory over Inter last season. Pastorello’s son Federico has followed in his father’s footsteps and is a sports agent with clients who include Romelu Lukaku, Kasper Schmeichel and Antonio Candreva. Meanwhile, with Maurizio Setti, Verona once again find themselves in the hands of a President with limited capacity to invest in the club, yet again a source of frustration for the fans.

The Mister

The season before Parks began the project that would become A Season with Verona, a newly promoted Verona were led by a charismatic and innovative young coach named Cesare Prandelli. Prandelli had confounded the critics by finishing in a respectable ninth place, thanks to a remarkable fifteen game unbeaten run – a sequence which included rare victories against Juventus and Lazio.

A clash of egos between Prandelli and Pastorello resulted in the coach being moved on that summer (what a different book Parks might have written had Prandelli’s contract been extended). Prandelli went on to achieve great success elsewhere, most notably with Fiorentina and the Italian national team, reaching the final of Euro 2012. Now 63, he is still remembered fondly for what he achieved in his two years in Verona, and in particular, for that unprecedented fifteen game unbeaten run.

In the summer of 2000, Prandelli was replaced by Attilio Perotti, a reserved journeyman coach in his fifties. He had never coached a Serie A side before and struggled all season to inspire his players. Parks describes him as “bland, too-amiable….He wears glasses. His chin is weak….”, and when he finds himself sitting next to Perotti on a flight, is somewhat deflated when the taciturn coach reads a Ken Follett book for the duration of the journey.

At the end of the 2001 season, Perotti passed to southern rivals Bari, where he spent two unremarkable seasons, followed by short spells at Empoli, Genoa and Livorno. After a career spanning five decades, Perotti’s days as a coach finally grounded to a halt in 2014. His record with Verona, promotion to Serie A in 1996, and dramatic salvation in 2001 ensure his place in the history books, but he never fully enjoyed the affection of the Curva.

The Players

During the summer of 2000, Prandelli’s squad was dismantled, with Sébastien Frey, Gianluca Falsini, Fabrizio Cammarata and Alfredo Aglietti following their coach to the exit. The team was almost entirely rebuilt. A host of new arrivals included Adrian Mutu, Alberto Gilardino, Emiliano Bonazzoli, Massimo Oddo and Mauro Camoranesi. Talented young players, but lacking experience at that stage in their career. In one of many thoughtful passages, Parks offers a tantalising insight into the more mundane side of life for a modern Italian footballer, as he prepares to meet them ahead of a big away game. Despite his excitement about the prospect, Parks is left decidedly underwhelmed by the whole experience, and would have preferred to have spent the time with his friends on the Curva. .

The Foreigner

Adrian Mutu, a young Romanian striker who had been rejected by Inter, made his first significant appearance in the book when he scored and enthusiastically celebrated in the Partita della fede (the Match of Faith). The young Romanian clearly hadn’t read the script, as this was a charity match that no one was supposed to win, let alone celebrate doing so. Mutu scored four goals that season (and twelve the next), before going on to enjoy spells at Parma, Chelsea, Juventus and Fiorentina. A formidable talent on the pitch, off it he was difficult to manage and never far from controversy, later serving bans for testing positive for cocaine and other controlled substances.

The Wonderkid

Just 18-years-old, striker Alberto Gilardino arrived in Verona on the eve of the 2000 season. After scoring five goals in 39 appearances at Verona, he went on to become one of Serie A’s most prolific ever goal scorers, playing for Parma, Milan and Fiorentina, and picking up a World Cup winners medal along the way. He is currently head coach of a relaunched Siena in Serie D.

The Oriundo

Born in Argentina but with Italian origins, Mauro Camoranesi was another who enjoyed a glittering future after launching his career with Hellas in the 2000/01 season. He went on to make 224 appearances for the Bianconeri and 55 for the Italian national team and, like his old teammate Gilardino, picked up a World Cup winners medal in 2006. Painting a typically vivid picture, Parks describes Camoranesi like this:

“Small, barrel-chested, a helmet of Indios black hair, this boy is a collision of fury and talent. He loses his temper. He shouts. You can see he’s going to be sent off before the season is out. Sometimes he’s so determined to be clever he loses the ball too, he shuffles his legs this way and that so fast that he mesmerises himself, he can’t remember what he was supposed to be doing, the way sometimes a sentence, an idea, can become so over intricate, so self-regarding in its twists and turns, it collapses in on its own conceit and already the reader is looking elsewhere.”

The Soldier

A final mention for Massimo Oddo, another from that squad who would pick up a World Cup winners medal in 2006. Remarkably, Verona’s inexperienced young defender was doing his military service during the 2000-01 season, which meant that he spent half the week at the barracks cleaning guns and lavatories and doing field exercises and the other half with the team preparing for the match at the weekend. Not a concern for today’s players, as compulsory military service in Italy was abolished in 2005.

The Journalist

Back then, Matteo Fontana, Verona’s Gazzetta dello Sport correspondent, was completing the final stages of his law degree at the University of Turin. Already an avid student of the game, Fontana was a valued source of advice and input as Parks unwrapped the history of the club. Fontana’s favourite player that season was Michele Cossato. A local lad, he scored some crucial goals for Hellas, including the late winner away to a high-flying Parma in the penultimate game of the season. One might recall a youthful Gigi Buffon between the sticks for Parma that day. That unlikely victory would propel Verona towards a relegation tie-breaker with Reggina.

Twenty years on, Fontana remembers it as if it was yesterday,

In this “Paese dei mille campanili” (a reference to Italy’s renowned parochialism), Fontana acknowledges that A Season with Verona had a greater impact abroad than it did in Italy. It was, however, translated into Italian under the title Questa pazza fede (This crazy faith), but the bishop of Verona famously suggested that it should be burnt.

The Writer

As for Parks himself, it’s fair to say that he has moved on. He still writes about life in Italy (his latest book Italian Life is a self-styled fable exploring life in a paradoxical country), but he no longer lives in Verona and follows the club from a distance, making only a very occasional appearance on the famous Curva.

Speaking to the Crazy Faithful fanzine last year, he observed that “Fandom comes in waves. Football is there when you need it.” As for a sequel, his response was a resounding “no”:

“It was a fantastic time of my life and a fantastic experience that year when I travelled with the Brigate Gialloblù to all the games and barely did anything but live football and plan away games and make new friends and shout myself hoarse every week. I wouldn’t like to spoil it now with something that couldn’t catch that crazy energy.”

That’s a pity, but I guess we’ll just have to make do with the original. Afterall, A Season with Verona is still a great read. Just as captivating and just as relevant as it was twenty years ago. And with a wave of optimism once again surrounding Hellas Verona football team, what better time to revisit that tumultuous season.

Words by: @Rick_Hough