Teams do not usually sell their best player and go on to win the Champions League, but that’s exactly what Juventus did in the 1995-96 season. Roberto Baggio, perhaps the best player in the world at the time, was told in no uncertain terms that his salary was to be reduced by 50% if he were to remain at Juventus. Baggio’s contract had actually expired but, this being months before Marc-Jean Bosman’s landmark ruling, he could not join another club until a fee was agreed.

Juve’s derisory offer was more a message than a proposal: it was time to go. Marcello Lippi and the club’s infamous triad of directors – Luciano Moggi, Roberto Bettega and Antonio Giraudo – believed they had an in-house replacement in the form of the bushy-haired 20-year-old Alessandro Del Piero. Baggio, knowing his worth, was not prepared to take a drastic wage reduction, so a £6.8m deal was agreed with Milan. He would go on to win another Serie A title that season, but he would never be a European champion.

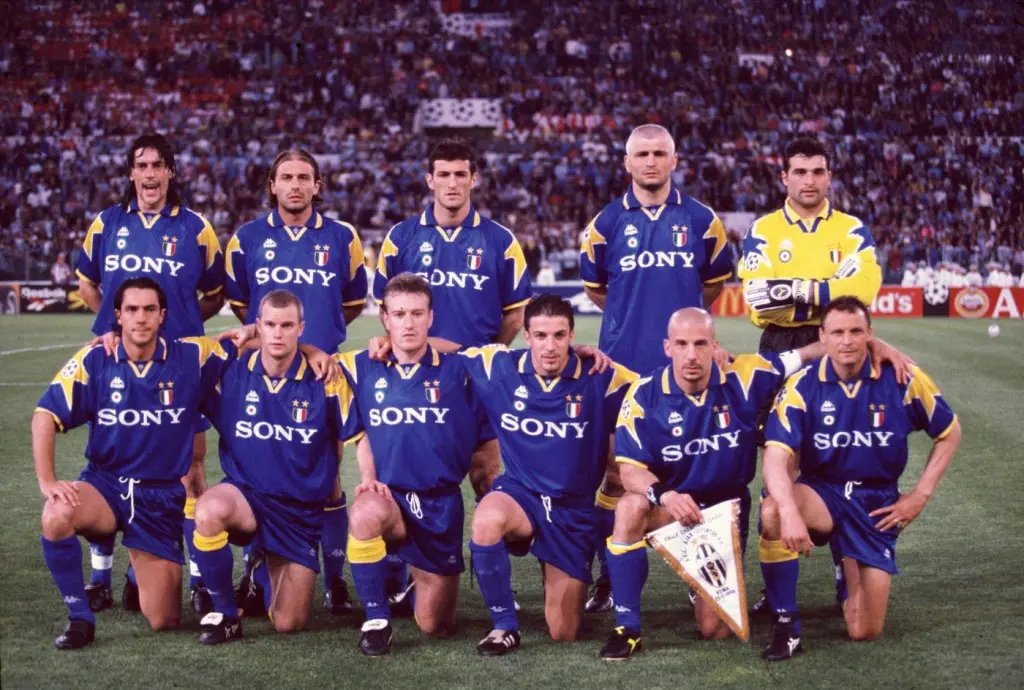

The other big departure in the summer of 1995 was the rugged German defender Jürgen Kohler, who joined Borussia Dortmund after four years in Italy. Juventus raided a downsizing Sampdoria for Pietro Vierchowod, Vladimir Jugovic and Atillio Lombardo, as well as signing Gianluca Pessotto from Torino, and Michele Padavano – who, like Lombardo, would go on to have a stint at Crystal Palace – from Reggiana.

The group stage

Juventus had not played in the European Cup since 1986, when they were eliminated by Real Madrid on penalties in the second round. This time they would at least be guaranteed six games. Drawn in a group containing Rangers, Borussia Dortmund and Steaua Bucharest, Juve were hoping to play a lot more than that.

They did not miss Baggio in the group stage, with Del Piero – who inherited the No10 shirt – sparkling. In Juve’s opener in Dortmund, he set up goals for Padavano and Antonio Conte either side of scoring a beauty of his own, hitting a sumptuous shot from the left-hand side – soon to be known as the Zona Del Piero – that nestled in the top corner of Stefan Klos’ goal.

After a comfortable 3-0 win over Steaua, Juve played back-to-back games against Rangers. Paul Gascoigne had joined the Scottish champions from Lazio that season to play in the Champions League and said he wanted “to do especially well against Juventus”. He missed the first game, which Juve won 4-0, and was inconsequential in the second, as Juve demolished Rangers 4-1 to end their hopes of reaching the quarter-finals.

With their own qualification all-but secured, Juve relaxed. Dortmund, who met Juve four times in 1995, got their only win in late November at the Stadio delle Alpi. The Germans also qualified, edging out Steaua, who only scored twice in six games yet somehow finished above Rangers.

The knockout stage

By the time the quarter-finals rolled around in early March, Juve had already surrendered their Serie A title to Milan, who were 11 points clear. They had also failed to retain the Coppa Italia, losing in the third round to Atalanta. All of their eggs were now in the Champions League basket.

Real Madrid awaited in the quarter-finals. The pair had only met twice before in Europe, and the Spanish side had progressed on both occasions. History looked like repeating itself when Madrid won the first leg 1-0 at the Bernabéu, courtesy of a Raúl strike. Juve overturned the result in Turin though, with goals from Padavano and Del Piero securing a 2-0 win.

A vastly underrated Nantes side, which contained a young Claude Makélélé, proved tougher opposition than expected in the semi-finals. Juve won the first leg 2-0 in Turin thanks to goals from Gianluca Vialli and Jugovic, and Vialli scored early in the second leg at the Stade de la Beaujoire to extend their lead.

Vialli had struggled to convert his league form to European nights while at Juve but he rose to the occasion in the semi-final, setting up Paulo Sousa to give Juve a 4-1 lead after Eddy Capron had pulled one back for Nantes. The French champions scored two late goals to win on the night, but Juve went through 4–3 on aggregate to face reigning champions Ajax in the final.

The final

The final, held on a stuffy May evening in Rome, was a clash of ideologies: Dutch idealism against Italian pragmatism. “We took pride in our tactical ability in that Juve side,” reflected Vialli in his autobiography, The Italian Job. “We understood the benefits of changing things around and trying different systems.” While Ajax coach Louis Van Gaal stuck to his 3-1-3-3 system, Lippi had alternated between a 4-3-3 and a 4-4-2 that season depending on which players were available.

Along with Del Piero, the Ajax forward Jari Litmanen had been the standout player in the competition that season but, looking back on the game 25 years later, Jugovic says Juve were not worried about the opposition. “As this was my second Champions League final, I was focused solely on winning,” he says. “And I was also confident in myself and the team.”

The final was only the third time in 11 games that Lippi was able to field his favoured attacking three of Del Piero, Vialli and Fabrizio Ravanelli, and it was the ‘White Feather’ who gave Juve the lead in the 13th minute. Seizing on a lack of communication between Frank de Boer and Edwin van der Sar on the edge of the area, Ravanelli nipped between the pair and, on his weaker foot, somehow angled a shot that crept over the line.

Litmanen equalised four minutes before half-time after Juve failed to deal with a De Boer free-kick. Both sides came close in the second half: Vialli failed to connect properly with a Ravanelli cross; Del Piero fired straight at Van der Sar; Patrick Kluivert’s header glanced wide; Vialli pounced on a loose ball in the area and rounded Van der Sar but, with the goal gaping, hit the side netting; and Jugovic and Del Piero nearly settled it in extra-time.

Penalties beckoned. “After full-time, I was calm,” recalled Lippi last year. “Everyone came towards me and told me they wanted to take a penalty.” Edgar Davids went first for Ajax and he missed, handing the advantage to Juventus. Ciro Ferrara, Litmanen, Gianluca Pessotto, Arnold Scholten and Padavano all scored to put Juve 4-2 up in the shootout.

When Sonny Silooy’s shot was saved by Angelo Peruzzi, Jugovic stepped up knowing that, if he scored, Juve would be crowned European champions for the second time in their history. “In those moments your only hope is to see the ball hit the back of the net,” he says. “I made my choice [on where to place it] relatively easy.” The rest is history. Jugovic smashed the ball low and hard to Van der Sar’s right, and Juve had won the Champions League. They have not won it since.

The aftermath

As Baggio had discovered the previous year, there was little sentimentality at Juventus. Ravanelli, Vialli, Sousa and Vierchowod were moved on weeks after the victory in Rome. Ravanelli and Vialli were replaced by Christian Vieri and Alen Boksic; a young Zinedine Zidane took over from Sousa; and Paolo Montero replaced Vierchowod.

The changes hardly made a difference, as they reached another Champions League final in 1997, but unexpectedly lost 3-1 to Borussia Dortmund. “Even though the final was in Munich, they had the advantage of playing at home in Germany,” says Jugovic. It was his final game for the club before he too was moved on, alongside Vieri, Boksic and Lombardo.

Yet Juve kept moving. They reached a third successive final in 1998, this time against Real Madrid, but a goal from Predrag Mijatovic made sure The Old Lady fell short once again. “If you reach the final three years in a row it means that you are dominating European football,” said Lippi, who suggested burnout contributed to their defeats in 1997 and 1998. “We went to the final always winning the Serie A title, except in 1996. It is difficult to carry on in two competitions.” Despite losing two finals in a row, they became the measuring stick of the era, with Alex Ferguson later admitting: “Juventus were the model for my Manchester United.”

Italy’s most dominant side have become the Champions League’s greatest losers, losing five finals since their triumph in 1996. “It’s difficult to believe that a club such as Juve have only won two titles after having played in so many finals,” says Jugovic. The Serb’s winning penalty gave him cult hero status at the club. Given how they have performed over the last couple of seasons, it’s difficult to see any current Juve player earning the same position any time soon.

Words by: Emmet Gates. @EmmetGates