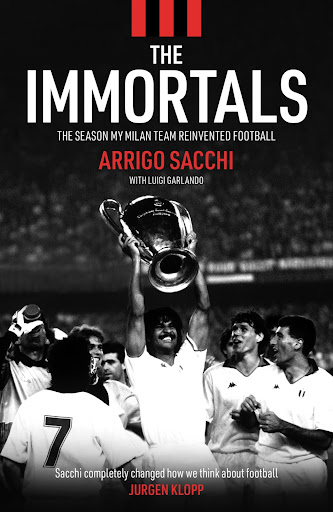

It is well known that judging a book by its cover is a mistake, but the title of Arrigo Sacchi’s recently translated book about his victorious 1989 European Cup campaign reveals its strengths and weaknesses: There’s self confidence and there’s calling a book about your own team, The Immortals.

Arrigo Sacchi’s credentials need very little introduction to even the most casual football fan. His AC Milan side of the late 1980’s and early 1990’s won a Serie A and two European Cups but, perhaps more importantly, they did so playing a thrilling brand of attacking football that placed vast emphasis on pressing and teamwork. Despite Sacchi’s celebrated achievements, the reader is often told, on the front and back cover and most of the 174 pages, that Sacchi changed the face of the game and heralded the modern era. It is this tone which gives the impression that this book is an attempt to cement a legacy that is already here – it comes across as both insecure and narcissistic – in other words, exactly like Sacchi himself.

Despite the fact Luigi Garlando is credited alongside Sacchi, there can be no accusations of ghost writing here which is also an indication of Mark Palmer’s fine translation. The narrative voice is so strong that, at times, it resembles David Pearce’s wonderfully demented fictionalisation of Bill Shankly’s internal monologue in Red or Dead, than it does a piece of footballing non-fiction. This is enabled by the excellent use of Sacchi’s Smemoranda, his notebook that he kept throughout the 1988/89 season. Even after convincing victories, Sacchi wants more – whether it is better finishing after winning 6-0 or holding nothing back in his assessment of the star players of his squad. As a reader, I was frustrated that more wasn’t made of this fantastic resource, the specifics of Sacchi’s intense drills needed to execute his pressing style of football are fascinating. Perhaps these notebooks could be edited and released at some point in time: they are an essential part of Calcio history.

The book is at its best when it shares footballing insight with the reader, the chapter on the controversial European Cup second round tie with Red Star Belgrade being a particular highlight. His description of Roberto Donadoni’s life threatening on-pitch injury is haunting and the atmosphere of the Marakana comes across with an infectious viscerality. For all of Sacchi’s ego, it is also pleasing to see the focus he places on the role of less celebrated members of the squad.

After finishing the book, there is a strong impression that Giovanni Galli, Angelo Colombo, Alberico Evani and Pietro Paolo Virdis played just as much of a part in winning the Cup as the glittering Dutch trio of Marco van Basten, Ruud Gullit and Frank Rijkaard. The specificity with which Sacchi writes about each player’s role is also satisfying but the man’s genius is so clear that it is frustrating to see him fall down in other areas of writing.

All autobiographies are, by their very nature, one-sided but there are descriptions of people and events from the past which are charmlessly biased. He presents Napoli’s second Scudetto victory in 1990, for example, as something his side was tricked out of (due to Napoli being awarded a win for crowd trouble against Atalanta) and the primary reason for his exit from Milan.

No mention is made of Milan losing three out of their seven final matches of that season (arguably down to fatigue from Sacchi’s methods) and, in actual fact, he departed a full season later after another Scudetto failure. Worse still is the way former club President, ex-Italian Prime Minister and convicted criminal Silvio Berlusconi is fawned over in sickly prose.

These sections read more like something from the ex-premier’s current campaign to become President of the Republic, than a balanced view of his legacy. The flaws in tone, however, are also the book’s strengths, since there is enjoyment to be found in spending time with one of football’s most successful eccentrics, even if this unreliable narration is, at times, problematic from the perspective of people coming to these events for the first time.

Despite these criticisms, The Immortals is, without doubt, an essential read for all followers of Calcio. The problems that readers might have with it are, perhaps, the problems that Sacchi had as a coach but this immersion into his world-view is an opportunity that is not to be missed. This is true even if I came away from it with a view of the man more akin to Roberto Baggio in USA ‘94, than Angelo Colombo in Barcelona ‘89.