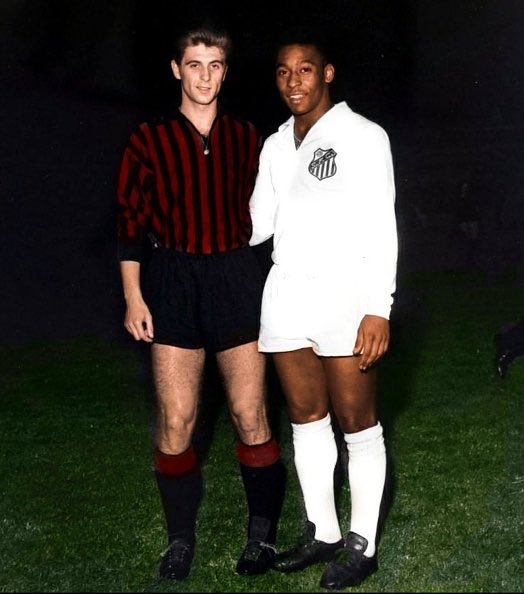

Milan, October, 1963. Pelé and his Santos team have come to town to play the first leg of the Intercontinental Cup final against reigning European champions AC Milan. It’s Pelé’s second competitive club game in Europe, following his hat trick triumph in Lisbon in the same competition in 1962.

Italy is no alien territory for the great Brazilian – at this point he’d played 12 games and scored 14 times against Italian sides. According to some, he spent a day (technically) as an Inter player after the 1958 World Cup before the move was vetoed and Juventus also came within a whisker of securing his signature three years later.

If events had worked out slightly differently, the outpouring of grief and emotion that was triggered by Pele’s death could have been all the more acute in Italy. The San Siro, where this meeting of legendary sides took place in 1963, could now be in the process of being renamed the Stadio Pelé.

Instead, he’d go on to play a total of 38 games against some of the greatest Italian club teams of all time and score 41 goals. His most memorable night on the peninsula happened under lights in a wintery Milan in 1963.

Build Up

AC Milan in 1963 were a fine vintage and deserved European champions. They’d beaten the favourites Benfica in a Wembley final a few months previously which sealed Nereo Rocco’s status as a Milan managerial legend. He was replaced by the double European Cup winning Argentinian Luis Carniglia but the playing side remained largely the same.

Legendary attacking midfielder Gianni Rivera was just twenty but he had exploded onto the scene already and the Italian Press were delighted at the prospect of seeing two stellar Number 10’s face off in this fixture. Milan also boasted two World Cup winning Brazilians: number 9, Jose Altafini, a 1958 world champion, who, with 14 goals, had just secured the record that would stand for fifty years in the European Cup. He had just represented Italy at the 1962 World Cup having switched allegiances owing to his perception of Brazil’s habit of not selecting oversea players. Alongside him in the rossonieri number 11 shirt was Amarildo who had recently signed from Botafogo after winning the World Cup for Brazil in the previous year. Pelé’s replacement in that tournament would face off against him in the San Siro. Milan also boasted 24 year old defensive all rounder Giovanni Trappatoni and a captain colossus at the back called Maldini, Cesare (Paolo’s father).

Santos were much more than a one man team. Pelé, however, was in his prime during this era. His performance against Benfica in the previous year was arguably his best club showing and his recovery from injury following the 1962 World Cup had gone well – he scored one of the most important goals of his career just a month before – the winner in the 1963 Copa Liberadores final away at Boca Juniors. It is still regarded by many as the highest quality edition of the competition with players such as Garrincha, Alberto Spencer, Antonio Rattín, Nilton Santos and Jairzinho all taking part

Alongside Pelé were many of his teammates from the 1962 World Cup triumph. Goalkeeper Gilmar and deep lying playmaker Zito had lifted the trophy twice in a row, whereas midfielder Mengálvio and strikers Coutinho and Pepe were part of the ‘62 squad. Zito, in particular was (and is) a Santos legend and his midfield partnership with Didi in the 1958 World Cup might be the greatest double pivot in the history of the game.

The atmosphere in Milan was electric. The booming city, packed full of recent economic migrants from across the country had the pleasure to see two superclubs facing off against each other in their rapidly expanding and increasingly trendy city.

The Match

The game began at breakneck speed as both sides sought to land an early blow from their glittering forward lines. There were chances for both sides within two minutes – Santos’ chemistry between the Zito led midfield and the Pelé led attack was clear from the outset. Milan, however were clearly a wonderful team and Rivera, Altafini and Amarildo formed a fluid and dangerous attack. The first goal, after just three minutes came from an unlikely source. The blonde haired Trappatoni received the ball thirty yards out and let rip a perfect low strike to put Milan ahead. He was mobbed by teammates and photographers rushed on to the pitch to capture the moment. Going ahead against the legendary Santos team clearly meant a lot to this side.

Milan continued to impress – their back line marshaled by Maldini coped much better with the dangers of Santos than the Brazilian side handled the European champions. Amarildo was the star of the opening periods, causing problems in and outside the box. Fifteen minutes in, Santos failed to clear another Milan attack and Mario David’s deep cross from right was headed in by the Brazilian number 11. 2 – 0 to Milan and Pelé’s 1962 replacement appeared to have entirely stolen the limelight.

Pelé could be forgiven at this moment for thinking that Milan was a cursed place for him. Earlier in the year, Santos participated in a triangular friendly tournament with Milan and Inter, lost both games and failed to score. Now, with the world watching, his side simply could not contain Milan’s dynamic attack.

Pelé, however, was Pelé and came out in the second half and started to dominate proceedings. Around ten minutes into the half, Pepe dribbled forward, fed the ball to Coutinho who passed back to Zito. Zito came forward and got the ball Pele, who was tightly marked with his back to goal on the right hand side of the penalty area. Then the sheer quality of Pelé was revealed to the watching thousands in Milan: He turned, effortlessly beat his marker before bursting into the box with electrifying acceleration. He passed another defender before firing with characteristic power and accuracy into the bottom left hand corner.

There was more than one world class Number 10 playing in this match and Gianni Rivera, perhaps inspired by Pelé’s own brilliance, started to purr. Twelve minutes after the Santos goal, Maldini’s long ball found Rivera just in front of the halfway line. A deft touch took him past Mengálvio before he launched a inch perfect twenty yard lofted pass to Amarildo on the left flank. The Brazilian took a touch and blasted it into the Santos net to make it 3-1 and continue the barely believable world class play from both sides.

Rivera wasn’t finished, however. Fifteen minutes later he burst forward from the halfway line once more and, having been giving a criminal amount of space by Mengálvio, had the time to place an exquisite pass to Bruno Maro. Maro hit it without taking an extra touch and Gilmar was beaten for the fourth time. Rivera was just twenty and, during this passage of play at least, had outshone his counterpart in the ten shirt.

There was one piece of drama left in this compelling match up. Five minutes from the end, the provider of Milan’s second David handled in the box and a penalty was awarded to Santos. As Pelé prepared to take the penalty his Brazilian team mate, but Milan rival, Amarildo walked over to his goalkeeper, Giorgio Ghezzi to offer some insider knowledge. Pelé was seemingly affronted by this and gave Amarildo a shove. Had this gamesmanship put O Re off his stride? Absolutely not, his staggered penalty approach, which seems so modern to look back on, beguiled Ghezzi and the Milan leg of the final finished 4 – 2.

The Aftermath

Milan’s victory at home turned out to be Pyrrhic. The highly controversial return leg in Brazil finished 4-2 to a Santos side without Pelé with two of their goals coming from free kicks in the second half. Argentinian referee Juan Brozzi was savaged in the Italian press and he was swiftly removed from officiating FIFA accredited matches in the future.

A playoff match two days later was settled by a Santos penalty awarded by Brozzi who also sent off Maldini for protesting. Pelé had recovered enough to feature and add yet another winners medal to his collection. Milan who had seemed so composed and together in Italy failed to bring these qualities overseas.

Perhaps the accusations levelled at Pelé’s performances outside of his homeland should instead be directed at the great Milan side, even if they were hugely hard done by with refereeing decisions. What is without question, is that anyone lucky enough to be in the San Siro that October night in 1963 would have no doubt that Pelé’s incredible gifts were realised on European shores as well as all around the world.