By the 1990s, the loophole that allowed footballers to play for more than one country had long since been closed. However not since the Oriundi of 1934 had Argentinians been so prominent in Italian football.

This was highlighted during Argentina’s 1998 World Cup campaign. Their last 16 tie against England was a classic encounter and among English fans, the game is best remembered for David Beckham’s infamous sending off. However from an Argentine and Italian perspective, it was hard to ignore the overwhelming presence of Serie A players in the Albiceleste squad.

That night in Saint-Ètienne, no less than eight of Argentina’s starting 11 were playing their domestic football in Serie A. Diego Simeone and Javier Zanetti had just finished the season at second placed Inter, while Matias Almeyda and Jose Chamot plied their trade at Lazio. Roberto Ayala continued the tradition of Argentines at Napoli and Abel Balbo had just enjoyed a successful season topping the scoring charts at Roma. Finally Juan Sebastián Verón and Hernan Crespo (who had come off the bench) had just qualified for the UEFA cup with Parma. The team could have almost been mistaken for an all-star Serie A XI. Moreover, these Argentines were instantly recognisable to English fans thanks to Channel 4’s hugely popular Football Italia show.

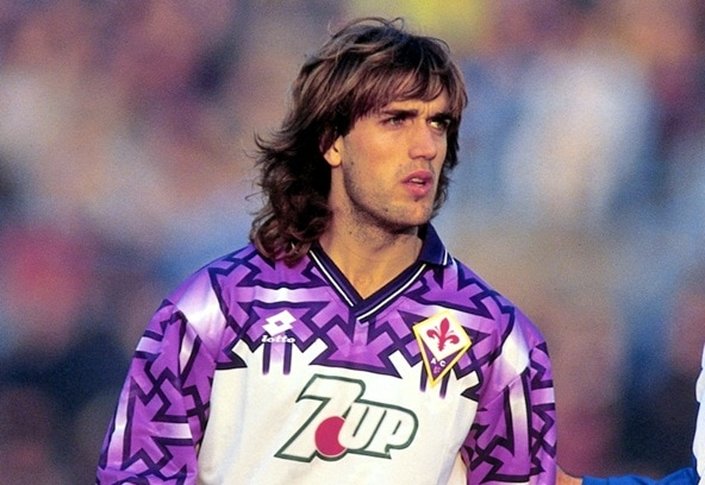

One of the most iconic members of this Argentina side was Gabriel Batistuta. Nicknamed “Batigol”, his flowing long hair and purple Fiorentina shirt lit up our television screens, firing in stunning goals week after week – becoming widely recognised in England thanks to Football Italia. The striker – who amassed 168 goals in 269 appearances for Fiorentina – was described by compatriot Diego Maradona as the “best striker I have ever seen.” And just like the great Maradona before him, Batistuta was yet another example of an Argentine flourishing in Serie A. Another match made in the Italo-Argentino heaven.

However, Batistuta’s career and route to Serie A was altogether different to other Argentinian players who had been seduced by the potential wealth that the bel paese could offer. As a young boy growing up in the small town of Reconquista in the Argentinian countryside, football was not of great interest to him. He was a studious person and was wary of giving up his education in order to pursue a career in football. It was Jorge Griffa at Newell’s Old Boys that saw potential in the player, even though “he didn’t look like a footballer.” The youth team coach persuaded him to join the club in 1988 and a successful season prompted a move to River Plate just one year later. Then, in 1990, he earned a move to the club he had supported as a boy – Boca Juniors.

Impressed by his performance in the 1991 Coppa América (he finished the tournament as top scorer with six goals) Fiorentina officials approached Boca Juniors. Batistuta had a different mind-set to other footballers, he was fond of his home in Argentina, and a career in football had not been his dream from the outset. After his move to Florence, he started slowly and struggled to adjust to life in Italy. However, just as his initial resistance to a career in football resulted in him becoming one of the sport’s greatest ever strikers, his initial apprehension at a move away from his country led to an unparalleled nine year love affair between the tifosi viola and Batigol – their very own messiah.

But aside from the goals and destroying of traditionally impenetrable Italian defences, what was different about this ‘complete striker’? His allegiance to Fiorentina when they were relegated to Serie B in 1993 is something that set him apart from other players. By the mid-1990s, his reputation was such that he attracted offers from clubs such as Real Madrid and Manchester United. But his loyalty to Fiorentina was unwavering and his 16 goals helped seal their return to Serie A the following season.

His response when questioned about his reasons for not joining a top club when he was at his peak was that giving 100% on the pitch was more important than winning trophies, preferring not to join a team where winning was a given.

In the 1999-2000 season, English followers of Football Italia were rewarded with the chance to watch Batigol play against an English side when Fiorentina took on Arsenal in the Champions League group stages. The Argentine striker did not disappoint, <smashing an emphatic goal home from an impossibly tight angle to seal a 1-0 victory.

The second group stage saw Batistuta and Fiorentina terrorise reigning champions Manchester United at the Stadio Artemio Franchi, their dynamism coercing the English football powerhouse into uncharacteristic mistakes. The 2-0 scoreline was thanks to a composed Batistuta strike; punishing a horrible back-pass from Roy Keane. Goal-scorer then turned provider, as Batigol forced the United defence into yet another misplaced pass, setting up fellow Argentinian Abel Balbo. It was a memorable night for Fiorentina, their hero spearheading a surprise result against a team of the calibre he once chose to reject.

Batistuta reminding Manchester United’s Gary Neville of the score during their Champions League clash in Florence

Yet despite the goals, magic moments and adoration, Batistuta had spent nine years with no league title to show for his efforts. It was a similar story during his international career. His 56 goals in 78 appearances for Argentina made him the all-time top scorer for La Albiceleste, but there was to be no World Cup winner’s medal to cap his career.

Domestically, the search for the coveted Scudetto meant it was time to seek pastures new, and Fabio Capello secured his services at Roma for a £23.5 million fee that reflected his monumental reputation; one which remains the highest ever paid for a player over 30-years-old. He scored 20 goals in 2000-01 as he clinched his first ever league title in a team that included Vincenzo Montella, Francesco Totti and Cafu.

Success in the capital was regrettably short lived for Batistuta and the following season yielded only six goals in 32 appearances. Roma fans were beginning to lose patience with an ageing striker who had seemingly lost his acclaimed goal-scoring touch. As a consequence he was loaned to Inter (who had lost striker Hernan Crespo to injury) in January 2003.

Batigol scored just two goals in his six months with the Nerazzurri, as it became evident that his sparkling career in Serie A was over. His final retirement came in 2005, after scoring 25 goals in a two year spell for Qatari side Al-Arabi.

Following retirement, his adopted city of Florence seemed the logical location for Batistuta to settle with his family – three out of his four children were born there, and many other Argentinians had settled in Italy following a career in Serie A. Nonetheless, it is not a surprise that the man who was initially reluctant to seek a career in football went back to a quiet life in Argentina.

Florence is still very much part of his heart though, as he remains a frequent visitor to matches. In October 2014, he wept as he was inducted into Fiorentina’s hall of fame. It was an indication of just how much his time in the Renaissance city meant to him, a relationship between club and player that transcended success and winning trophies.

Standing next to him on the stage was his 19-year-old son Lucas, himself having signed with the Viola. He currently plays for their affiliated team, CS Porta Romana, perhaps leaving room for another chapter in the Batisuta-Fiorentina love affair. But filling his father’s boots will be nigh on impossible. For there is only one ‘Batigol’ in Florence.