It could be said that the San Siro has an association with Silvio Berlusconi in much the same way that La Scala has an association with Verdi. Many of Italy’s greatest operatic artists and finest singers have appeared at La Scala over the past 100 years. This is a theatre regarded as one of the leading opera and ballet venues in the world and is home to the La Scala Theatrical Chorus, La Scala Ballet, and the La Scala Theatre Orchestra.

The San Siro, just like La Scala, is another world class artistic home located in the northern Italian powerhouse city of Milan. Over the years it has played host to many of football’s greatest artists, from Gianni Rivera to Marco van Basten and Franco Baresi. And, if there are parallels between the two venues, likewise there are parallels between the two men.

Both Verdi and Berlusconi were men of Italian patriotic rhetoric, and both were Italian parliamentarians. Both used respective creative artforms as a political tool whether to progress notions of unity, progress or freedom.

Then of course there are what history defines as the ‘less amiable’ personal qualities of both.

In the case of Berlusconi, his personal conduct lends itself almost always to lampooning. Tales of sexual controversy, bunga-bunga parties, false accounting, tax fraud, mafia association, financial dishonesty, judicial reviews and media manipulation followed his long reign at AC Milan.

However, in football politics can often be forgotten, at least for 90 minutes. Each one of the fans who stand weekly on the Curva Sud will have their own individual political views and personal political ethics. Many will be left wing, many more to the right, while others simply wont care. Quite simply, for many followers of Milan, Berlusconi was a hero to the club, while for others his political reign at the top of Italian politics was nothing but a pain.

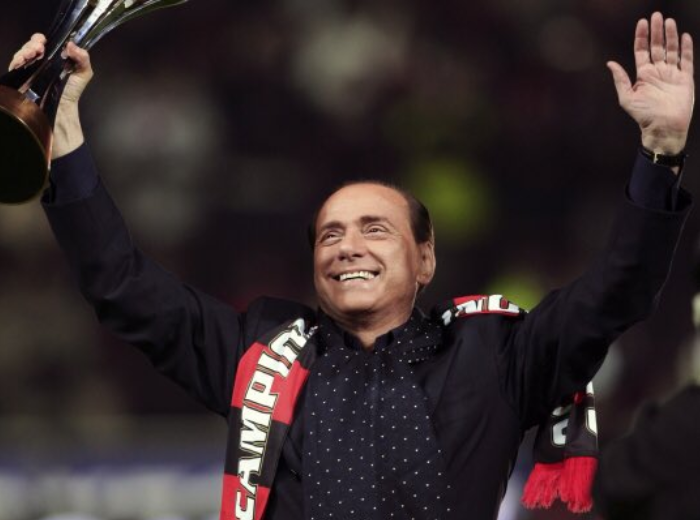

In late November 2016 the fans on the Curva Sud unfurled a huge choreography dedicated to Silvio Berlusconi the football man – ‘coreografia decicata Berlusconi’. If ever the views of Milan followers were required it was etched so clearly into that display. As the rival players entered the field of play the tifo content was rich in imagery, symbolism and words. Political controversies aside, this was only a stark appraisal of Berlusconi the football man, vivid in all its colour.

For one night the theatrical protagonists of the Milan ultras had as its leader Silvio Berlusconi.

Not for Berlusconi a megaphone and baseball cap, instead more an image of this great football leader surrounded by domestic titles and European Cups.

Born in Milan on 29 September 1936, Berlusconi came from a steady middle class family—his father being a bank employee, and his mother a housewife. At University he studied law, eventually graduating in 1961 where he specialized in the legal aspects of advertising. During his academic years he worked as a cruise ship singer, a musical taste that came to pass in later years when he wrote an anthem for AC Milan.

The 1960s saw his entrepreneurial skills and business acumen come to the fore. Soon he was dabbling in commercial property and buying land for apartments. The energetic 1970s saw him take over the presidency of a number of organizations including Fininvest and Italcantieri while more tellingly in 1977 he acquired a share in a newspaper. By the 1980’s he was networking in political circles (former PM Bettino Craxi became a noted friend) and he was operating successfully in broadcast media.

In football terms, by 1986 AC Milan had arrived at a point where a major change was required at a resourceful and richly traditional club that had fallen behind Juventus in matter of both global prestige and finance. On 24 March 24 1986, Berlusconi took over, being named Milan’s 21st president in the process. At a press conference a few days after buying the club he declared: “Milan is a team, but it’s also a product to sell; something to offer on the market.”

The Curva Sud’s last derby choreography was dedicated to the exploits of their inimitable Presidente

Quickly the new man reinforced his sales pitch with insightful purchases. In came the likes of Roberto Donadoni, Giuseppe Galderisi, Daniele Massaro and goalkeeper Giovanni Galli. As with any club it would take the new arrivals time to gel, but the real catalyst for change was the arrival of head coach Arrigo Sacchi and the Dutch trio of van Basten, Frank Rijkaard and Ruud Gullit.

By 1988 Milan were again Scudetto winners, overcoming Diego Maradona’s Napoli at the top of the table. A noted 3-2 win in on 18 May 1988 gave Milan its 11th title and the first of the Berlusconi era. Another landmark success followed in May 1989, with Milan ruling their continent again after lifting the European Cup.

However, the Sacchi reign, no matter how successful, did not last forever. Next came Fabio Capello, but the same pattern of domination at home and abroad continued. Rijkaard called the Milan playing culture of the time an ‘intense’ period of football success.

But even during the periods of success the managerial position proved to be an unstable one. After Capello’s first spell came Oscar Tabarez, Giorgio Morini and then the returns of both Sacchi and Capello. Domestically Milan never had things to themselves with Juventus fighting back and pushing them at home and in Europe. More tellingly, by 1994 Berlusconi had entered directly into politics, having founded the Forza Italia party.

By the start of the new millennium newer names were to be found in the San Siro dugout and the Sacchi era was a distant memory. Alberto Zaccheroni, Cesare Maldini, Fatih Terim and Mauro Tassotti held the reigns of power. Then came the very successful reign of Carlo Ancelotti, which coincided with Milan reaching the very pinnacle of European football once again in 2002 and in 2007. Since then the club has seen Leonardo, Max Allegri, Clarence Seedorf, Pippo Inzaghi, Sinisa Mihajlovic, Cristian Brocchi and now Vicenzo Montella at the helm as manager.

The Berlusconi era at Milan was mostly one spoiled by success, but these days the Rossoneri are largely in the shadow of a hugely powerful Juventus side. In recent times that have missed out on the Champions League, with even Europa League football off the radar.

Once key players in both national and international football scenarios, the club seem to be entering a post-Berlusconi period and are preparing for new achievements supported by the enthusiasm of many fans around the world. The club continues to promote itself as a ‘big brand’, carefully harnassing new media tools such as Twitter, YouTube and Facebook in order to place its name at the forefront of global football.

Berlusconi’s personal conduct over the years has, in some cases, led to anger. At times it was impossible to read any Italian magazine without his slicked back transplanted hair and toothy white grin looking back from the front cover. But whatever you think of him, his reliance on the force of personality and media power added up to a hugely successful combination.

The darkest elements of Berlusconi’s cult like grip on Italy need no exploration here. And just how an ageing billionaire managed to manipulate the Italian legal and political system to be repeatedly re-elected as Prime Minister is something that needs to be asked of the voting Italian population.

But it says a lot that pundits can barely mention his name without raising an eyebrow. Despite being an ambassador for world football, at times Berlusconi’s comments on everything, from women to sexuality and racism, have drawn rightful criticism. He chose to make verbal gaffs and even share jokes with famous contraversial figures; pictures of him sharing jokes with Colonel Gaddafi are well known.

Today, Juventus and AC Milan are quite possibly Italy’s most modern and progressive clubs. Both apply astute business strategies and entrepreneurial spirit as part of wider large-scale global conglomerates. But equally, both club perhaps lack the presence of the forceful key Presidential figurehead of old.

The splendid architectural image of the San Siro remains one known for the unique corner helicopter landing type ramps that allow access to the stadium levels. Internally, its spectacular structures illuminate a playing surface that has become iconic here in the UK since Italia 90. Back in 1980, the San Siro was named ‘Giuseppe Meazza’ to honor the unforgettable player who was twice a world champion with the Italian national team. Yet one still wonders if the reaction would be positive should a stand ever be renamed in honour of its unforgettable president, Silvio Berlusconi.

Words by Damon Main: @TheAwaySection

Founder of www.theawaysection.com, Damon is currently based in Scotland. From his first football match in 1978 to more recent times, Damon somehow still manages to combine his sense of wanderlust with a camera and laptop.