Walking down Avenida de Hércules in the Spanish city of A Coruña today, it is hard to imagine that this busy one-way road that runs through the heart of the Monte Alto barrio, once traversed a quiet family neighbourhood where kids could play football in the street all day without fear of encountering a motor vehicle.

In the 1940s, however, the tall commercial buildings and blocks of flats that now line the avenue did not exist. And the inhabitants could enjoy far-reaching views to the Roman lighthouse, known as the Tower of Hercules – a privilege now reserved for only a handful of fortunate residents.

In the period following the Second World War, there were very few affluent citizens in this humble neighbourhood. Most families could barely make ends meet and luxury items were the stuff of fantasy. But it was here, on these wet and windy Galician streets, where Spain’s only male Golden Boot winner and one of Internazionale’s greatest ever players first developed his footballing skills.

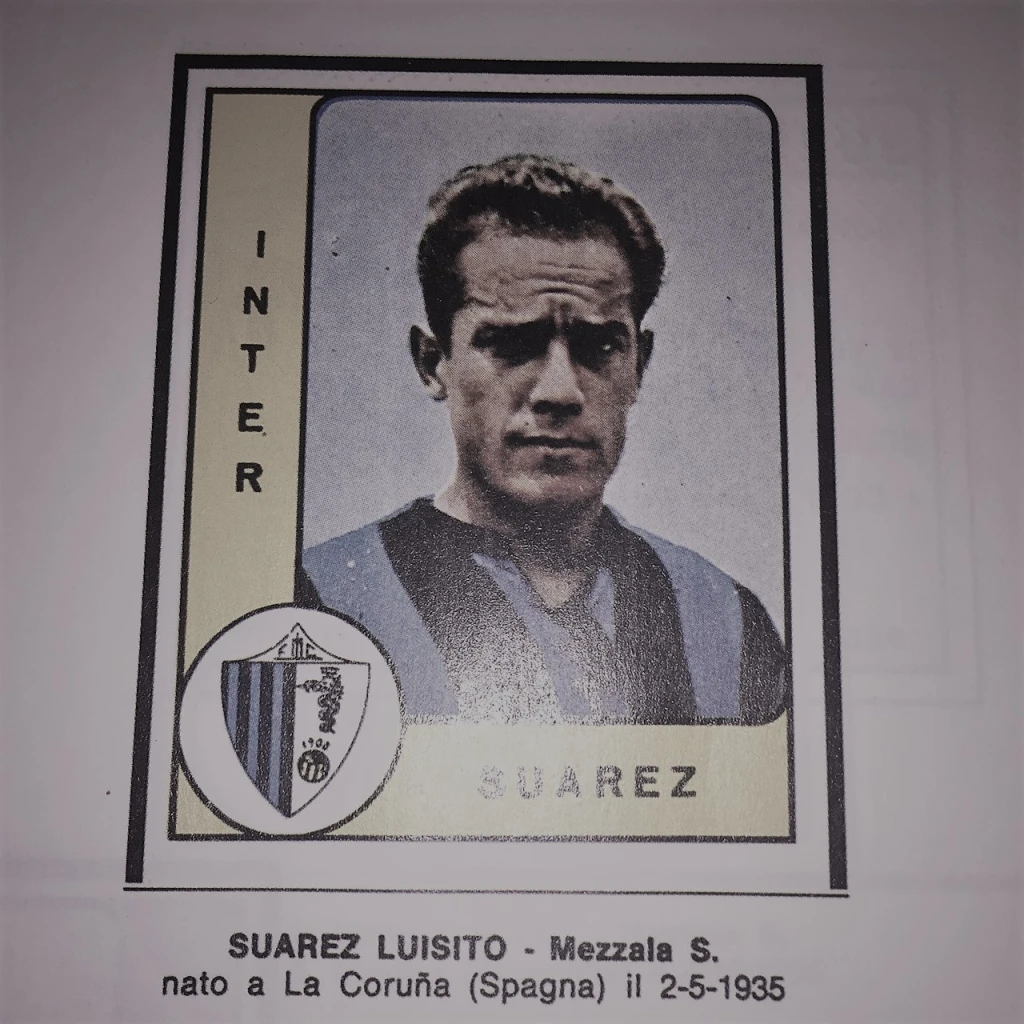

When he wasn’t helping in the family butcher’s shop, Luis Suárez Miramontes (known to his family as Luisito) loved to play soccer. But the cost of a regulation football was beyond the reach of most families in the area, so he and the other children had to make their own balls out of old rags. The final product was not ideal, especially on wet days, but with a few repairs here and there, the cloth balls could last for weeks on end.

The other challenge that faced the young players was the weather. The streets and beaches where they played were exposed to fierce Atlantic winds that would snatch the ball from their feet swifter than the toughest defenders. The team playing into the wind had to adapt their game accordingly, often taking hundreds of touches just to get near the opposition goal. It was for this reason that the pre-match toss – to decide who played at which end – was the most important moment of the day.

The combination of a makeshift ball, poor footwear and adverse weather conditions forced Luisito to develop a highly-precise technique and great game instinct. Even when the young player was finally able to step away from the streets and onto the turf to represent one of his local clubs, proper footballs were rarely used and he had to patch up the holes in his old shoes rather than buy new ones.

In 1952, thanks to his consistent performances for local teams such as Accion Catolica de Santo Tomas, Hercules de la Coruna and Perseverancia (managed by the local priest), Luis Suárez eventually forced his way into the youth set-up of local La Liga side, Deportivo La Coruña. The Galician club were enjoying a sustained spell in the top flight and had recently constructed a new stadium on the site of their old pitch.

Just two years earlier, under the guidance of Argentinian coach, Alejandro Scopelli, Depor had finished second in the league, just one point behind champions Atlético Madrid. Immediately after arriving at the club, Scopelli established a soccer school for youngsters and it was from here that Luisito was drafted into the club’s new set-up. Initially, he was loaned out to lower league side Fabril Sociedad Deportiva, with whom he achieved promotion to the third division, but after just one season, aged 18, he made the step up to the senior side.

While Luisito could now enjoy such luxuries as proper football boots, track suits and hot showers, the training conditions were still poor. Coaching sessions took place on a wet, muddy field which was exposed to those same Atlantic winds; but of course, he excelled in these conditions and thought nothing of it. In fact, he later claimed that training on such pitches helped him to develop the game intelligence and technique that would serve him so well later in his career. And during his professional life, he never once complained about the condition of the pitch.

Luis Suárez made just 17 appearances for his home town club, the most significant being a 3-2 win away to Sporting Gijon, during which he was scouted by Barcelona Sporting Director, Antoni Tamburini (the youngster had made his top-flight debut in a 6-1 defeat to the Catalans and had caught the eye of Coach Helenio Herrera).

At the time, Barcelona were negotiating the purchase of Depor’s Uruguayan striker Dagoberto Moll but having watched the game in Gijon, Tamburini insisted that the young midfielder should be included in the deal. The Catalans eventually parted with 800,000 pesetas in exchange for both players.

Following his transfer, Suárez played in Barcelona’s subsidiary team, España Industrial, before joining the senior ranks a year later. During his time at the Camp Nou, Luisito established himself as a creative midfielder with an eye for goal and helped to guide the club to two league titles, two Copa del Rey’s and two Fairs Cups (predecessor to the UEFA Cup). He played alongside such names as Ladislao Kubala, Zoltán Czibor, Sándor Kocsis, Ramallets and Evaristo; and trained under the guidance of the aforementioned Herrera, who would go on to become a good friend as well as a mentor.

Such was his impact at Barcelona, that in 1960, Luis Suárez was crowned the European Footballer of the Year; and to this day, remains the only male Spanish-born player to have won the Ballon d’Or (Di Stéfano had Spanish nationality but was born in Argentina). He was nominated for the prize eight times in total, being named runner-up in 1961 and 1964, and ranked third in 1965. Such was his importance to the Barcelona blueprint, that Di Stefano dubbed him “the Architect.”

In 1961, the Architect made one of his last appearances for the Catalan club, in the final of the European Cup against Béla Guttmann’s Benfica side at the Wankdorf Stadium in Bern. Despite taking the lead through Sándor Kocsis after 21 minutes, Barcelona were outplayed for much of the first half and by the hour mark, they were 3-1 down. A goal from Zoltán Czibor after 75 minutes gave the Spanish side a glimmer of hope, but they could not find an equaliser.

Shortly afterwards, Barcelona accepted a world record offer of 250 million Lire (over €200,000 in today’s money) from Italian side Inter for their star player. Barca’s decision to sell was prompted by the huge debts that they had accumulated while constructing their brand-new stadium. At the time, the transfer fee eclipsed the previous record (165m Lire) paid to River Plate by Juventus in 1957 for Omar Sívori. But the record was smashed just two years later by Roma who paid Mantova 500m Lire for the services of Brazilian striker Angelo Sormani.

Luis Suárez’s achievements at Inter cannot be over-stated. Few players in the world today can dream of attaining such success. In his second season at the club (1962-63), he became a Serie A champion, a feat he would repeat in 1964-65 and 1965–66. He helped the club to win back-to-back European Cups in 1963–64 and 1964–65, and consecutive Intercontinental Cups in 1964 and 1965. All of this was achieved under the guidance of his former Barcelona boss, Helenio Herrera, who had taken over the reins at the Nerazzurri in 1960.

Soon after receiving his first European Cup medal in 1964, he also became a European champion at international level as part of Spain’s 1964 Euro Championship winning side – a feat that remained unmatched until 1988 when a handful of PSV Eindhoven players also claimed Euro doubles for club and country. Five years earlier in 1959, Luis Suárez had become Spain’s first ever goal scorer at European Championship level, grabbing the opener in a 4-2 qualifying win over Poland. Remarkably, Helenio Herrera was also in charge of the Spanish national team at the time.

A few years after joining Inter, Suárez returned to Barcelona to play a friendly match. Every time he touched the ball he was jeered by the home crowd, an act that provoked an angry reaction from the player who gestured towards the fans. The truth was, he never fully settled in Catalonia and was plagued by homesickness. At the time, the Spanish press created an internal rivalry between him and Kubala which in turn divided the home crowd. Such pettiness was not evident in Milan, where he was universally adored by his adopted city. He later told biographer Marco Pedrazzini that he felt like “an Italian born in Spain.”

When analysing his time at Inter it should be noted that Helenio Herrera, known in Italy as ‘Il Mago’ (The Magician), effectively built his team around the Spaniard. And by switching him to a deeper role, he enabled the midfielder to dictate the play with greater effect (hence later comparisons between Suárez and Pirlo). Of course, he became less potent in front of goal but the overall benefit to the team was worth that sacrifice.

His influence off the pitch was also important to the team. When the players were lining up in the tunnel to face Real Madrid in the 1964 European Cup Final, Suárez noticed that many of the Inter squad were staring in awe at Di Stefano. Even amongst professionals, the man known as the “Blond Arrow” was treated as a legend and an idol. Suárez felt his players were not focused on the job in hand and immediately launched into a series of rally cries to break them from their trances.

Of course, arch rivals AC Milan had won the trophy the year before, and Suárez was not going to let anything distract his teammates from matching that feat. He was also looking to atone for his own disappointment, having lost the 1961 final to Benfica while playing for Barcelona. Not only did Inter beat Real Madrid comfortably (3-1), but they also retained the trophy a year later by defeating Benfica 1-0 at the San Siro.

In total, Suárez spent ten seasons at Milan before heading to Sampdoria in 1970. He spent three years in Genoa before finally hanging up his boots and embarking on a 20-year managerial career that would see him take charge of Deportivo, Inter and the Spanish national team.

After retiring, he did not return to Spain, preferring instead to remain in Milan, the place he now regards as home. However, he has not lost touch with his roots and continues to visit A Coruña, where his nephews still live in the house where he was born.