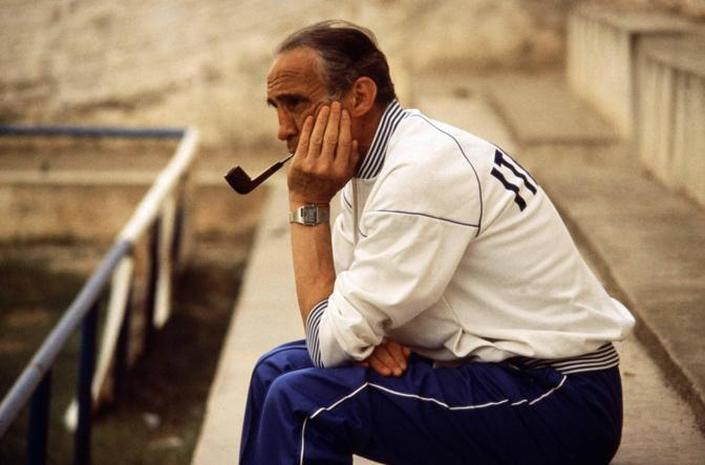

One of the best known pictures in the history of Italian football shows four men engaged in a game of cards on an airplane table. On extreme left corner sits bespectacled Italian president Sandro Pertini, musing over his next move. Beside him, Enzo Bearzot biting a pipe that has now become synonymous with him. Opposite the Italian coach sits Dino Zoff, looking innocuous for a man who at 40-years-old, has just set a record unlikely to ever be broken. To Zoff’s left one can see Franco Causio oozing the class and sophistication that had earned him the nickname of “Il Barone”.

Yet, these four famous Italians are only supporting cast in this picture. The star of the show sits on center of the table, football’s most famous trophy, the Jules Rimet, which itself is partly Italian, sculpted by Silvio Gazzaniga. It’s a great picture, radiating swagger of an understated sort. For many Italians this picture, along with a bunch of other memorable ones from 1982 represents an emotion that is unique, unsurpassable. The drama of 1982 also fogs out the bedrock on which it was built – Italy’s superb performance in 1978 World Cup.

Italy’s post-War record in World Cups was mediocre as they struggled to replicate the form that had seen them win consecutive titles in the 1930s. The national team took a long time to recover from the tragic loss of Grande Torino, whose players formed the core of Azzurri in late 1940s. Italy bowed out in group stages of 1950 and 1954 World Cups, while in 1958 they had to suffer the ignominy of not qualifying, courtesy of a loss against Northern Ireland. The trend of group stage exits continued into the 1960s as La Nazionale went deep into the daze of ultra defensive football. These exits also carried a degree of notoriety, be it the infamous “Battle of Santiago” in 1962 or the shock loss to North Korea in 1966. At this point, the national team was getting accustomed to a barrage of rotten tomatoes after every World Cup campaign.

Feruccio Valcareggi was able to stop the rot and spark Italy’s first successful era since the 1930s. Under him, Italy won their first and to date only Euro title in 1968. At the 1970 World Cup, Valcareggi’s Italy played one of their greatest ever matches, defeating West Germany 4-3 in the semi-final before falling to Pele’s Brazil in the final. Four years later, Valcareggi lost the dressing room, had a well publicized fallout with Giorgio Chinaglia as Italy endured yet another group stage exit. A year after the debacle of 1974, Valcareggi’s assistant Enzo Bearzot was handed the reins – a glorious era was about to begin.

Bearzot started his Azzurri head coach career at a time when Turin was dominating Serie A. Between 1974 and 1978, the Scudetto made its way to the Piedmontese capital for four consecutive seasons. Under the tutelage of Giovanni Trapattoni, Juventus won three league titles and the European Cup Winners Cup. Juve’s exceptional defense also made up Italy’s back line. Veteran Dino Zoff was in goal, protected by prodigal greenhorn Antonio Cabrini alongside Gaetano Scirea and Claudio Gentile, who in their mid-20s were about to enter their prime. In midfield, Italy called upon the combative pair of young Marco Tardelli and experienced Romeo Benetti. Prolific Roberto Bettega led the forward line and had scored 17 times for Italy in 24 matches between 1976 and 78.

Going toe to toe with their crosstown rivals, Torino had won Serie A in 1976 and then clinched podium finishes in the following two seasons. The Granata’s strength lay in their striking pair of Paolo Pulici and Francesco Graziani. Together they had plundered 36 goals in Torino’s league winning season before Graziani finished as Capocannoniere the following season.

Along with Graziani, Bettega and Pulici, Italy’s forward quota was completed by a 21-year-old striker whose 24 goals had propelled minnows Vicenza to a surprising second place finish in 1977-78 season – one Paolo Rossi, future hero of the 1982 World Cup winning side. Meanwhile, Giancarlo Antognoni, creative engine of a young Fiorentina side that had won the Coppa Italia in 1975, was one of Azzurri’s midfield linchpins.

Spain 1982: Enzo Bearzot and the birth of ‘Silenzio Stampa’

Italy began their World Cup qualification campaign on 13th June, 1976. In Group 2, Finland and Luxembourg were minnows and the lone qualification slot was a shootout between Italy and England. Bettega was in sparkling form during qualifiers and scored nine goals, including four against Finland. “Bobbigol” also found the net against England in Rome, helping Italy to a 2-0 victory after Antognoni had put them ahead. However, England turned the tables in London, reversing the scoreline. In the end Italy and England finished level on points but Bearzot’s penchant for attacking football bore fruit as the Azzuri qualified thanks to better goal difference.

In 1986, when Mexico hosted the World Cup, Uruguayan coach Omar Borras used a phrase that has now become famous – “Group of death”. If the phrase was popular in 1978, then it would have been aptly applied to Italy’s group in 78′. Hungary had leapfrogged Soviet Union to qualify for the tournament but were expected to be the weakest side in the group. Under Michel Hidalgo, France had an exciting team and were one of the dark horses. The presence of hosts Argentina, aiming to win their first World Cup, further complicated things. To make matters worse, the Azzurri dished out a series of indifferent performances while preparing for the main tournament. The bookmakers had no faith in Italy, placing odds of 200-1 on the team to reach the final. World Cup official film “Campeons” emphasized the same narrative: “The Italians in particular had been savaged by their media. Their fans expected nothing of it.”

Italy kicked off their campaign against France on 2nd June at the newly opened Estadio Jose Maria Minella in Mar del Plata. Under Michel Hidalgo, the French played an enterprising and attacking brand of football, lining up in an innovative 4-2-1-3 configuration with Platini as their creative engine. Within 38 seconds of kickoff, it seemed like the out of form Italians would wilt in front of the French assault. France’s keeper rolled the ball towards winger Didier Six, who started a lung bursting sprint covering almost the entire field. The Italian defense saw his threat late – both Scirea and Gentile were hopelessly out of position when Six finally crossed. His cross was met by a leaping Bernard Lacombe for one of the fastest goals in World Cup history.

To their credit, Bearzot’s team didn’t implode and slowly took control of proceedings. Tardelli shadowed Platini, muzzling his effectiveness. The French defence also had a hard time dealing with Italy’s fluid offensive triumvirate of Causio, Bettega and Rossi. An equalizer was looking inevitable and it came just around the half-hour mark. Bettega set up Causio, who’s close range header ricocheted off the frame. French defence failed to clear the loose ball and it bounced off Rossi’s leg into the net. In second-half, Rossi took up the role of a creator – Renato Zaccarelli received his cross and unleashed a low shot past an unsighted French ‘keeper. For a team struggling with pre-tournament form, the 2-1 victory was just what the doctor had ordered.

Just like Italy, Hungary were one of the first successful European teams in World Cup history, reaching two of the first five finals. Hungarian football had then gone into terminal decline, which was all too evident when Rossi and Bettega struck in quick succession in first-half. Midfield hardman Benetti added a third in second half with a powerful long ranged effort. Italy could’ve easily scored more had Bettega not struck the post thrice, possibly a World Cup record. Remarkably, this was the first time ever that Italy had won its first two World Cup group games. With Argentina beating France, the Italians had also qualified for second round.

The third group match involved teams who were already through but were fighting for pride and a chance to stay in Buenos Aires for the second round. The hosts created early chances, Zoff palmed away a free-kick from Mario Kempes while Gentile cleared off the line after a lapse from Cabrini. Italian teams of past would have gone into shell in such situations but Bearzot had a different philosophy. His team went on the offensive and Argentine stopper Ubaldo Fillol had to make a sharp save off Bettega.

But the Italian striker would have the last laugh thanks to an absolutely gorgeous second half move. Antognoni found Bettega with a square pass, the Juventus striker passed to Rossi before rushing past the Argentine defence to complete the one-two. Rossi had his back to the goal but backheeled the ball unerringly in Bettega’s path who finished emphatically. For the first time since 1938, Italy had managed to win three consecutive matches in a World Cup.

The second round was an all European affair as Italy were drawn with West Germany, The Netherlands and Austria, who had surprised experts by topping their group ahead of Spain and Brazil. Defending champions West Germany, Italy’s first opponent in second round, had not been very convincing in the first round, drawing twice. It seemed even the Germans understood that Italy were in better shape and fielded a conservative lineup with five defenders. Staying true to their form, the Azzurri dominated the game, creating a number of chances. Unfortunately for Italy, Sepp Meier was in unbeatable form under the German bars. The eccentric Bayern Munich keeper made a string of top class saves, breaking Gordon Banks’ World Cup record of most minutes without conceding a goal.

The Dutch had defeated Austria 5-1 so Italy also needed to defeat them to keep pace with Oranje. Paolo Rossi struck early and the Azzurri could have easily increased their tally but failed to do so due to poor finishing. With Netherlands and West Germany drawing, Italy were level on points with the Dutch but behind on goal difference – the meeting between the two sides would decide who reached the World Cup final.

The top 10 Azzurri kits of all time

Bearzot’s team started brightly and went ahead in the 19th minute when Ernie Brandts scored an own goal. Italy didn’t sit back and continued to dominate, as the World Cup official film asserts: “there was only one team in it. The Dutch midfield was invisible, Krol and Brandts had to be everywhere in defence, sweeping up, holding the team together and keeping the dream alive”. Despite their domination, Italy failed to increase their tally and this profligacy would hurt them in the second-half.

In the 49th minute, Brandts made amends for his own goal by scoring with an unstoppable long ranger. This goal was arguably the turning point – the Dutch were invigorated while Italian shoulders dropped. Bearzot kept pushing his team forward but could do little when Zoff reacted late to another long ranged effort from Arie Haan, which clipped the post before going in. Italy needed to score twice in 14 minutes but the Dutch, filled with players who had reached the 1974 final, were too experienced and killed the game. The 1970s had started with Ajax’s “Totaal Voetbal” humbling Internazionale and Juventus in consecutive European Cup finals – 1978 brought yet another Italian scalp for the Dutch.

Missing the abrasive duo of Bennetti and Tardelli due to suspension, Italy lost the third place match to Brazil. Nevertheless, there are two reasons why Italy’s 1978 World Cup team was significant and why they deserve to be eulogised. First, an overwhelming number of players from the class of 1978 were also pillars in the triumph of 1982. For many of these players, the tournament in Argentina was their first major outing. The experience of defeating the hosts under tremendous pressure as well as the failure to maintain their tempo against Netherlands would all add to the mental strength the squad showed in Spain. Zoff, Scirea, Gentile, Tardelli, Cabrini, Rossi and Antognoni were all regular starters in the World Cup winning team of four years later. A number of Italian players also won plaudits for their individual performances in Argentina; Cabrini won the best young player award while Bettega and Rossi featured in the team of the tournament.

Second and perhaps more importantly, the impact was in terms of tactics. Since the advent of Catenaccio, the Italian national team had wholeheartedly adopted this approach and subsequent Italian coaches refused to give up their ultra defensive philosophy, even when the system lost its fizz. Under Feruccio Valcareggi, Italy played their most attacking football in years during the 1970 semi-final against West Germany. However, that match was an anomaly, a desperate gamble in a must win match against a well organised rival. Despite having superb attacking players like Gigi Riva, Roberto Boninsegna, Gianni Rivera and Sandro Mazzola, Valcareggi’s Italy was still a largely conservative side.

It can be argued that Enzo Bearzot and his team of 1978 took the most important step for Gli Azzurri in terms of modern tactics. While attacking, Italy essentially played a 4-2-1-3 formation in Argentina. Benetti was the anchor in midfield and acted as a defensive shield, while Tardelli played a more box-to-box role. Antognoni with his creative edge played just behind the three front men. Franco Causio usually took up the role of the right sided attacker. On paper, Bettega was the offensive fulcrum, the big-centre forward. However, on the field, the Juventus striker would often outfox markers by drifting to left-wing. He had a brilliant understanding with Rossi and their clever interplay and changing of position made Italy’s attack extremely dangerous.

Bearzot’s team was a new Italy not just tactically but also how they approached games. Unlike preceding Italian teams, they didn’t retire into a defensive shell after taking a lead, but continued pressing forward. This bravado would help Italy four years later when they faced Argentina, West Germany and especially against Tele Santana’s sensational Brazil.

Enzo Bearzot’s new approach and the experience his team picked up during a deep World Cup run was of paramount importance for 1982. And thus, the class of 1978 deserves to be cherished for preparing the groundwork for Italy’s most famous triumph to date.

Words by Somnath Sengupta: @baggiholic