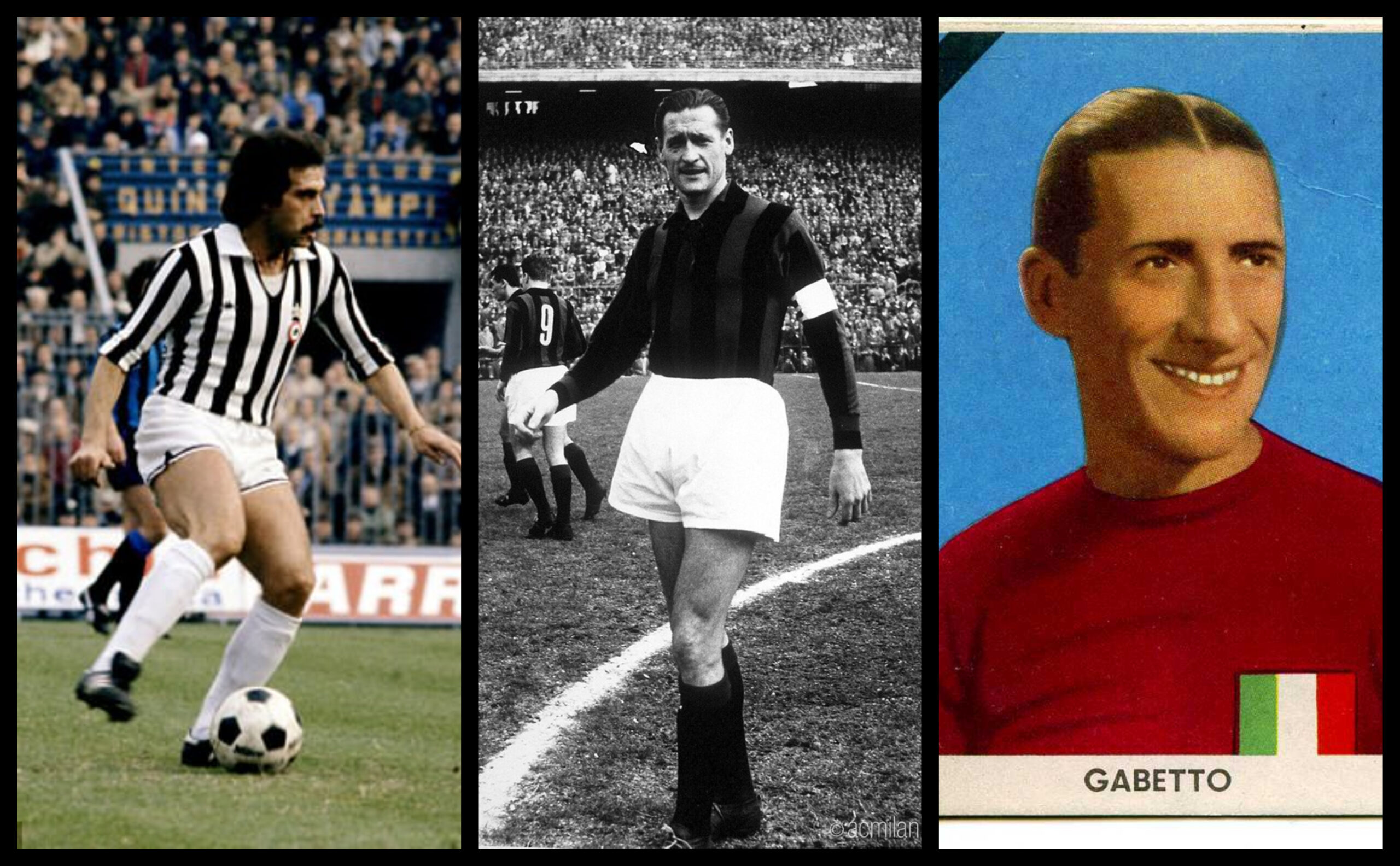

All the world’s national and club teams have nicknames but the Latin countries lead the way when it comes to player soubriquets. Argentine football history can be measured out with Flacos and Locos, in Brazil and Spain pet names often replace full names. In Italy, footballers’ nicknames tend to be either the spontaneous creations of fans or the imaginative concoctions of journalists, allotted on the basis of physical attributes, resemblances with other famous people, style of play or comportment on and off the field. The tre Baroni, or three Barons – Guglielmo Gabetto, Nils Liedholm and Franco Causio – fit into the latter category.

*

GUGLIELMO GABETTO

In the course of his lifetime, Guglielmo Gabetto, born in the Turin working-class neighbourhood of Borgo Aurora on February 24 1916, experienced a monarchy, a fascist dictatorship and a democratic republic, with a colonial war, a world war and a civil war thrown in for good measure.

He was known as Il Barone on account of his suaveness. He donned tailored suits and silk ties, and wore his hair in a centre parting, plastered down with brillantina Linetti. Sartorially speaking, on the pitch he was a sort of proto-George Best, standing out from other players by leaving his shirt outside his shorts.

Like a match, Gabetto’s career consisted of two halves. A prolific centrattacco, he played seven years for Juventus and seven for Torino, scoring 87 goals for the former and 120 for the latter. He won one scudetto with Juventus and five on the trot with the legendary Grande Torino. He also played six times for Italy, bagging five goals.

Gabetto was a product of the Juventus nursery. As a youngster, he worked night shifts on the Piedmontese railways and trained in the mornings. After making his Serie A debut as a comparative unknown in a 1-0 away victory against Pro Vercelli on January 27 1935, he was annoyed when the papers spelt his name erroneously as Gabetti.

That season Juventus won the fifth scudetto of their famous quinquennio, with Gabetto making five appearances in all. The team celebrated at the Teatro Regio, Turin’s opera house, where, when he wasn’t distinguishing himself on the dance floor, he could be found having a smoke in the bathroom. He had no qualms about strolling round the streets of Borgo Aurora with a fag in his mouth, but at the party he was afraid of being caught in flagrante by general manager Barone Mazzonis – a real baron! – who had imposed a strict no-smoking ban on the team.

Celebration was followed by tragedy when, on June 14, Juventus president Edoardo Agnelli was killed in a seaplane accident. More tumult followed in October with Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia. When Juve’s regular centre forward Felice Borel was conscripted, Gabetto stepped up to the plate.

In his seminal Storia del calcio italiano, Antonio Ghirelli describes Gabetto as, ‘One of the most refined products of Turinese football’, while for Gianni Brera he was ‘gifted with fiendish astuteness’. In 1937, Il calcio illustrato speaks of his ‘shambling gait, quickness of reflex and astonishing ability to create space for himself in front of goal’. Arguably his greatest performance was against Bari on December 17 1939, when he scored five of the goals in a 6-2 victory.

Why Juventus decided to sell him to Torino in 1941 remains a mystery. Gianni Brera described the move as ‘sacrilegium’, though the 330,000 lire transfer fee wasn’t to be sniffed at in wartime. In the view of Gigi Gabetto, Guglielmo’s son, the Bianconeri felt his dad was past his best – even though he was only 25. It was a slap in the face but it inspired Il Barone to redouble his efforts with Torino.

In 1943, when Gabetto was called up to serve in the navy, one of his brothers in arms was team captain Valentino Mazzola. After a lot of string-pulling by Torino president Ferruccio Novo, the two were soon recalled to Turin, where they contributed to the war effort by working in Fiat factories.

Following the armistice of September 8 1943 stipulating Italy’s surrender to the Allies and with the championship suspended, Torino began touring the war-torn north of the country. The players’ match fees were paid in flour, eggs and butter, and after one game against Lecco they received 100 electric light bulbs.

Endowed with a cheerful character and an infectious sense of humour, Gabetto, the only member of the Grande Torino team to be Turin born and bred, was the life and soul of the dressing room. Sometimes his pranks bordered on the reckless. After one match in Trieste, he filled the boot of the coach with boxes of black-market cigarettes. When they were stopped by the police on the way home, the Torino directors had a lot of explaining to do.

The late and great Barolo winemaker and Juventus fan Aldo Conterno used to tell the story of how Gabetto once gave him a ride on the top tube of his bicycle when he was a kid. He was almost tempted to convert to Torinismo but decided that, ‘My first love was Juventus and I decided I would never betray them’.

Gabetto’s biggest mate in the Torino team was Franco Ossola, the right-winger. In April 1948, a month before England’s 4-0 annihilation of Italy at Turin’s Stadio Comunale, the two opened the Bar Vittoria on the central Via Roma. The bar, which became a favourite haunt of Torino footballers, stayed open in the 48 hours leading up to the match. It’s said that the English players, who were staying at the Hotel Principe di Piemonte, a hundred metres down the road in Via Gobetti, would occasionally pop in to fraternise.

Gabetto was famous as a latecomer but, alas, on May 4 1949 he didn’t miss the flight bringing the Torino team home from Lisbon, where they had played in Benfica captain Francisco Ferreira’s testimonial. Four hours later, he died with all the other passengers when the plane crashed into the basilica of Superga in the hills overlooking Turin.

Commemorating Superga and Il Grande Torino

*

NILS LIEDHOLM

After a career as a player and manager spanning seven decades, Nils Liedholm – Swedish by birth, Italian by adoption – died at the age of 85 at Cuccaro in the Piedmontese hills on November 5 2007. He had retired to the village to run his wine estate, Villa Boemia, with his son Carlo, himself a graduate of the Italian Football Federation’s Centro Tecnico in Coverciano. A few years ago, I had the pleasure of frequenting Carlo and, over a series of lunches and dinners at the villa, his memories of his father flowed as copiously as his Grignolino wine.

Nils Liedholm was called Il Barone on account of his gentlemanly manners and fair play (in his entire playing career he never received a single booking). The nickname may also have something to do with the fact that his wife – Contessa Maria Lucia Gabotto di Sangiovanni – was a Turinese noblewoman. An uncle of hers, Giulio Incisa di Camerana, was one of the founders of Juventus. Carlo said his mother wasn’t a great Calcio fan but that she would have liked to see her husband managing the Bianconeri, and that on two occasions he went close, once in the mid-60s and once in 1971.

Carlo’s parents met at the spa resort of San Pellegrino Terme in Lombardy, where his father was attending an AC Milan pre-season training camp and his mother was on holiday. When she first saw him in his baggy tracksuit, she mistook him for a workman, and they eventually fell in love playing table tennis in the hotel together. Nils Liedholm himself once revealed that, ‘When we first met, I told her that it was we Swedes who invented gymnastics, and we’ve been doing exercises together every morning ever since.’

After winning the football gold medal with Sweden at the 1948 London Olympics, Liedholm moved to Italy, where he played out his career for AC Milan from 1949 to 1961. As a coach he was associated mostly with AC Milan, who he managed on three different occasions, winning a scudetto in 1979, and with Roma, who he managed four times, winning a scudetto in 1983. Carlo said that, deep in his heart, his father was slightly more Milanista than Romanista but that, most of all, he adored the Roma fans.

After decades of catenaccio, Liedholm championed zonal marking and possession. His philosophy was that it was less tiring to have the ball at your feet than having to chase it. This was evident watching his scudetto-winning Roma team. The way it covered the whole pitch and its emphasis on technique reminded one of the Brazil team that beat Sweden in the World Cup final in 1958. Liedholm had captained Sweden in that match and it had clearly left a lasting impression on him. He ploughed the same furrow at AC Milan in a three-year spell from 1984 to 1987, leaving Arrigo Sacchi fertile ground to cultivate his own more dynamic interpretation of the model.

Carlo said his father’s favourite player of all time was Alfredo Di Stefano and that he set great store by skill and touch. ‘He himself was like a Brazilian who happened to be have been born in Sweden.’ He used to cite the example of Mauro Tassotti, who his father moulded from being a workmanlike defender for Lazio into a ball-playing attacking right-back for AC Milan. Liedholm also gave their Serie A debuts to the likes of Roberto Bettega, Giancarlo Antognoni, Bruno Conti, Franco Baresi and Paolo Maldini.

He seems to have had a particular soft spot for Carlo Ancelotti, partly because Signora Ancelotti was a fabulous cook and laid on a Pantagruelian lunch when he visited to finalise her son’s transfer from Parma to Roma. Carlo Liedholm used to say that of all contemporary coaches, Ancelotti was the one who reminded him most of his father.

Liedholm was buried – like Guglielmo Gabetto, incidentally – in Turin’s Cimitero Monumentale. In 2011, Carlo and his sons Paolo, a Milanista, and Andrea, a Romanista, instituted the Premio Liedholm, annual award to ‘champions on the field and gentlemen in life’. Not surprisingly, the first winner was Ancelotti.

Five years later, Nils Liedholm was inducted posthumously into the Italian Football Hall of Fame.

Juventus vs. Roma (1983): A titanic tussle between ruthless rivals

*

FRANCO CAUSIO

When I first came to live in Turin, the Juventus squad was undergoing a process of what Gianni Brera referred to as Aufsuedung, ‘southernization’, a term he borrowed from the Frankfurt School of social theory and critical philosophy. Hence the presence of the likes of the Sicilians Furino and Anastasi, Cuccureddu, a Sardinian, Longobucco, from Calabria, and Franco Causio, from Puglia, my favourite.

The evolution of the team mirrored that of the city, whereby hundreds of thousands of southerners travelled north to work in its factories. In his study L’immigrazione meridionale a Torino, the writer and critic Goffredo Fofi observed that, ‘during a Juventus-Palermo match, there were many enthusiastic immigrant Sicilian fans whose sons, by now like any other self-respecting FIAT workers, were supporting the home side’. Causio himself writes in his autobiography, ‘The legions of southerners who flocked to the Stadio Comunale dressed in their Sunday best found in “their” Juventus a sort of liberation, of redemption even’.

Those were years of not only social but also political upheaval, of left-wing and right-wing terrorism, the so-called ‘Years of Lead’. My father-in-law to be was head of security at Mirafiori, the main Fiat factory, and he used to tell me about the climate of violence there. Amid the general doom and gloom, going to the Comunale to watch Causio on a Sunday was a much-needed distraction.

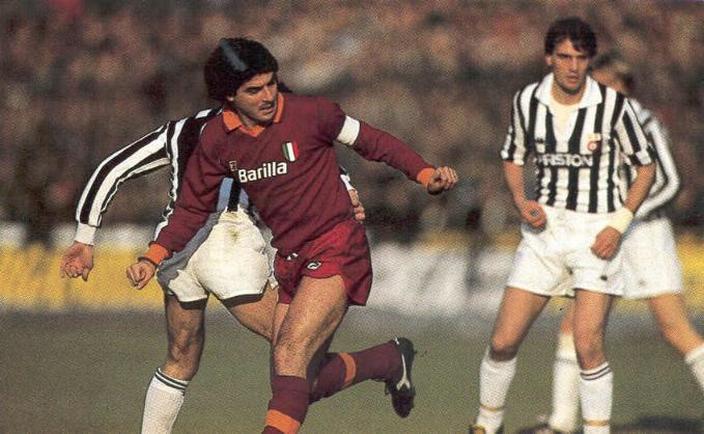

Born in Lecce on February 1 1949, Causio was nicknamed Il Barone by Fulvio Cinti of La Stampa for his debonair playing style. Gianni Brera went a step further with Barone Tricchetracche, a piece of onomatopoeia that conjures up fireworks on a patron saint’s feast day. The city of Lecce is famous for its baroque architecture, and ‘baroque’ was the adjective journalist Vladimiro Caminiti used to describe Causio’s technical repertoire. Causio has also fired the imagination of intellectuals. He was hailed by Paolo Bertinetti, professor of English literature at Turin University, as ‘more a pearl in the necklace than the cherry on the cake’ and for the literary critic Massimo Raffaeli he was ‘a baron of sulphureous, telluric aristocracy’.

Causio joined Juventus from Sambenedettese in 1966, and after making just one first-team appearance under Heriberto Herrera was loaned out to gain experience, first with Reggina, then with Palermo. He returned to the black-and-white fold in 1970 and made his debut on October 25, coming off the bench in the 65th minute of a home game against AC Milan.

‘Maestro, here’s your chance,’ said coach Armando Picchi, who later revealed that the only persone he had ever previously addressed as ‘maestro’ was Mariolino Corso, during his playing days at Inter.

Someone else for whom Causio became a maestro was Gian Piero Gasperini, now the manager of Atalanta, who joined Juventus as an apprentice in the early seventies. ‘I had the same boot size as Il Barone,’ he recalls, ‘and he used to give me his new ones to break in during training.’

Causio played 452 times for Juventus, scoring 72 goals. As a right-winger, he was a brilliant dribbler and crosser of the ball. But he also had an exceptional footballing brain and gradually assumed a more central regista-like role. When I saw Michel Platini make his home debut for Juventus in August 1982 in a Coppa Italia qualifier against Pescara, my first impression was that of a poor man’s Franco Causio. It’s true that he was suffering from a chronic groin injury that took six months to heal, after which he went on to live up to his own nickname of Le Roi. But it’s also true that the only player I saw at the Comunale who had superior ball skills to Il Barone was Maradona – and that was only in the pre-match warm-up.

It was because of his technical brilliance that Vladimiro Caminiti gave Causio a second nickname, Brazil. It’s no coincidence that in 1984 Causio teamed up with Zico at Udinese and went on to play in O Galinho’s testimonial at the Maracanà. Or that he fell in love not only with Rio but also with a carioca of almost half his age, Andreia Brito dos Anjos. The couple married in 2000 and now live in Udine, where Causio runs a sports shop and works as a TV pundit.

Il Barone was almost the last player to touch the ball in Italy’s 1982 World Cup final victory over Germany (Brazilian referee Arnaldo Cézar Coelho referee scooped it from his feet as he blew the final whistle) and was famously photographed playing cards with Dino Zoff, Enzo Bearzot and President Sandro Petrini on the plane home. If he didn’t already hold a place in the Italian collective consciousness, he has done ever since that episode.

Words by John Irving: @irving_john